How Electronic Visit Verification (EVV) Invades the Privacy of People With Disabilities

Sometimes the news isn’t as straightforward as it’s made to seem. Karin Willison, The Mighty’s disability editor, explains what to keep in mind if you see this topic or similar stories in your newsfeed. This is The Mighty Takeaway.

The United States government wants to track my movements. They want to know where I go, what I do, and who is with me every day. They’re setting up databases to track people like me right now. When they give the order, I’ll have to carry a special device, and I won’t be able to leave my home without notifying a government contractor.

I’m not a conspiracy theorist. I haven’t been arrested or committed a crime. A little-known provision of a 2016 law that goes into effect within the next two years threatens to steal the hard-won independence of millions of people with disabilities like me. It’s called electronic visit verification, and it’s even worse than it sounds.

I have cerebral palsy and use a power wheelchair, but I don’t let my disability limit me from living an active life. I live in my own home, I’m employed as Disability Editor here at The Mighty and regularly travel to conferences all over the United States speaking about disability issues. I’m also a travel blogger — that’s a job, not just a hobby — and I write about my experiences taking road trips across the country.

To live independently, I have personal care attendants (PCA) who assist me with getting out of bed, dressing, using the bathroom, cooking, house cleaning, shopping, driving and just about everything else. My PCA care costs about $4,000 per month, and no private insurance offers coverage for it. I have no choice but to be on Medicaid, and am in a self-directed Medicaid waiver program, in which people with disabilities control our own care. We hire our own personal care attendants, set the days and times they work, where they work and how they assist us.

People with disabilities have a constitutional right to live in our own homes and communities and make decisions about our lives, established in the Supreme Court ruling Olmstead v. LC. But now that right is under attack from an unexpected source. In 2016, Congress passed the 21st Century Cures Act. It was designed to streamline the approval of new medications and medical devices, but they slipped in another policy change many people didn’t know about. It’s called electronic visit verification (EVV). It requires all Medicaid funded personal care programs to implement a system for verifying a PCA’s identity and the date, time and location where personal care services were provided. If states fail to implement EVV by 2019, they lose up to 1 percent of Medicaid funding.

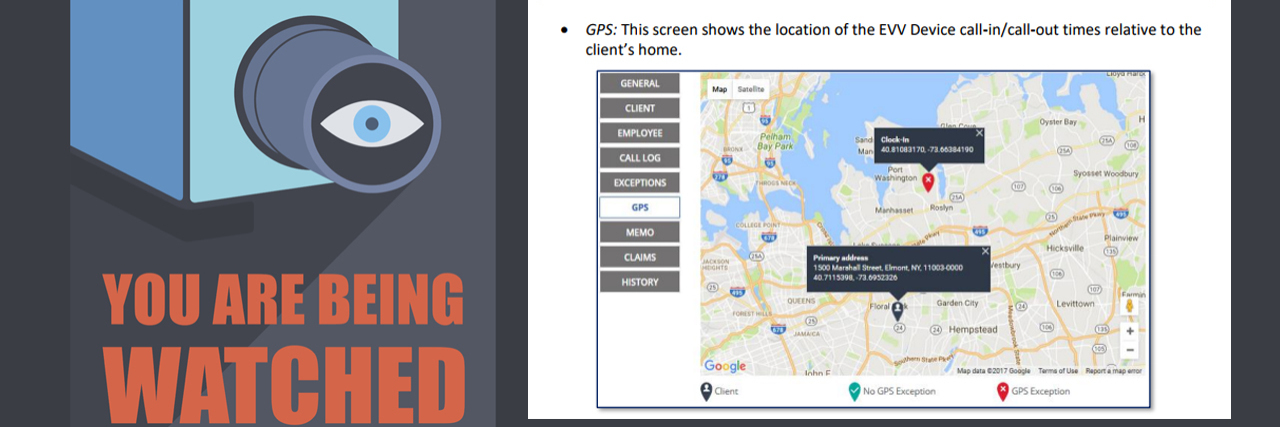

I live in a state that has yet to implement electronic visit verification for the waiver program I use. However, I am extremely concerned about the potential impact of EVV on my life and the lives of millions of other people with disabilities. Some states are already rolling out their systems, outsourcing them to private companies that are collecting our GPS locations and biometric identity data. These companies, notably Sandata Technologies, lobbied to have EVV tacked on to the 21st Century Cures Act. Now they stand to profit handsomely by invading the privacy of people with disabilities and our personal care assistants.

In January, the state of Ohio issued smartphone devices to PCA service users which they must take everywhere with them, essentially subjecting them to government surveillance at all times. These devices are monitored by Sandata and use their software for GPS tracking. If the device is more than 1000 feet from the disabled individual’s home or other “approved address” when a PCA logs in or out, it triggers an “exception” which must be reviewed. In other words, any time you’re not at home when your PCA logs in or out, the system won’t just record it; a government employee or contractor will look at it, know where you were and could even decide not to approve the “exception.” If you live in Ohio and need PCA care, without this approval, you’d be a prisoner in your home.

These screenshots from the Ohio Sandata EVV app show some of the data it collects:

![]()

![]()

Ohio isn’t the only state set to impose massive privacy violations on its citizens with disabilities. Here’s a form recently sent to self-directed personal care attendant service users in Massachusetts by Tempus Unlimited, a fiscal intermediary (payment manager). The form is titled “Consumer Multiple Location PCA Services.” It demands the person with a disability list the locations where they receive personal care assistance services and which PCAs assist them at those locations. It includes two spaces to list locations and two spaces to list PCAs who work in each location. If I had to fill out this form, I wouldn’t know where to begin. I can’t go anywhere for more than a few hours without a PCA, and I lead a busy, active life. Could you list all the places you visit every week, month and year? I’d need Google Maps for that.

Electronic visit verification seems to operate under the assumption that people with disabilities have a very limited existence. There’s no respect for our privacy or awareness that we do the same things as people without disabilities, such as work, shop, travel and have families. EVV steals the autonomy of people with disabilities and our right to live freely. It treats us like children who can’t manage our own lives.

The government should not have the right to know where I am at all times just because I have a disability and need PCAs. Electronic visit verification is the equivalent of putting an ankle monitor on people with disabilities and telling us where we can and can’t go. It turns having a disability into a crime.

Electronic visit verification interferes in the relationship between people with disabilities and our personal care attendants, treating them like criminals who must be monitored as well. Self-directed PCA programs specifically state the person with the disability has “employer authority;” therefore they should have no right to force me to use invasive tracking on my employees. I have multiple PCAs who have indicated they are not willing to be tracked by GPS or turn their biometric data over to a corporation, and I don’t blame them. As a domestic violence and violent crime survivor, I guard my privacy. I am cautious about allowing apps to access my GPS data and don’t even list the city where I live on Facebook. There’s no way I’d hand that kind of data over to an EVV app — and my concerns are already well-founded.

The Ohio EVV system is just rolling out, and already residents with disabilities and their PCAs have reported security breaches in Sandata’s app. In the Citizens Against EVV Facebook group, a PCA with one client reported that her account shows her as having two employees and seven clients, and listed their names and contact information. Another PCA with the same issue started calling the names on her list and discovered they were PCAs and clients in different cities and states. This isn’t just a horrific breach of privacy, it violates HIPPA by disclosing disabled individuals’ medical information to complete strangers.

By this point, you’re probably wondering, how can this be legal? With the disclaimer that I am not a lawyer, I strongly believe it isn’t. In United States v. Jones, the Supreme Court ruled that GPS tracking constitutes a search under the Fourth Amendment of the United States Constitution. That means for the government to track someone, they must either obtain consent or obtain a warrant, for which they must have probable cause to believe a crime is being committed. Unless there is evidence that people with disabilities and their PCAs are committing crimes, the state has no grounds to search us. Further, any consent given could be interpreted as illegally coerced since the consequence of refusing tracking could be the loss of life-sustaining health care.

The ostensible justification for GPS tracking is to prevent fraud and abuse in Medicaid personal care services. However, anyone who would advocate for such a system clearly lacks awareness of who receives PCA services and why. The majority of us have severe physical disabilities. We need and will always use the hours we receive; I’m not going to magically get up and walk or suddenly not need help using the bathroom.

As the employer of my PCAs, I am responsible for ensuring there is no fraud. Twice a month, my PCAs submit online timesheets to the fiscal intermediary payment system. I review each of them, affirm the timesheets are correct and approve the payment, just like any other employer. For people with intellectual disabilities or dementia, a family member can be designated and trained to handle these duties. A location tracking system is unnecessary and a massive violation of civil rights.

In my experience, the key to preventing fraud and abuse in Medicaid home care is the opposite of tracking technology — it’s human beings. It’s caseworkers who care about people with disabilities, address questions and concerns promptly and advocate for us. It’s also about valuing people — treating people with disabilities as the competent adults we are and supporting PCAs by paying them a wage that reflects their skill and hard work. In many states, flipping burgers pays more than helping a person with transfers, bathing, changing catheters or ostomies, maintaining a ventilator and other complex medical tasks. Low pay makes it hard to find good workers. Although many wonderful people still choose to do the job, there aren’t enough of them, and it also attracts individuals who are desperate and/or predatory. If we took all the money being wasted on electronic visit verification and used it to increase PCA wages, we could greatly reduce fraud and abuse by attracting higher quality workers to the field.

People with disabilities have a right to privacy like all other law-abiding citizens. Tracking our movements and shackling us to our homes like criminals is unconstitutional. We must fight this attack and preserve our human rights to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

If EVV has you concerned, here’s what you can do:

Sign the petition to stop Electronic Visit Verification.

Will EVV affect you? The National Council on Independent Living wants to hear from you.

If you’re an attorney, Citizens Against EVV is seeking help to pursue legal action.

Join the Citizens Against EVV Facebook group to help in the fight to preserve privacy and self-direction for people with disabilities and our PCAs.

Art via Getty Images.