A Letter to Dr. Linda Chavers about #BlackGirlMagic and Disabilities

According to her bio, Dr. Linda Chavers, is a writer, teacher and a scholar of 20th century American and African American literature with specializations in race and visual culture. Chavers recently wrote an article for Elle Magazine that discussed her problems with #BlackGirlMagic. This is my response to her article.

Dr. Linda Chavers,

I saw your piece at Elle Magazine. Did I think it was horrible? Yes.

But I’m not here to continue to drag you for it. Black Twitter already took care of that with #ChaversNextArticle. I am here to show you something you may not have thought about. I believe black women with disabilities have so much to celebrate using #BlackGirlMagic.

When we discuss #BlackGirlMagic and even #BlackLivesMatter, we often forget about those with “invisible” diseases or disabilities. I’m here to shine some light on a much-needed conversation.

My mother was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis (MS) when I was a teenager. And it broke our family to pieces. My mom was the head of household, raising three kids alone on a medical assistant’s salary. For years she worked third-shift, walking the enormous lengths of a hospital.

When the MRI confirmed multiple lesions were on her brain and the many complications of MS were listed, doctors knew her job would be taxing on her health and suggested she find another career path. For a few years, my mom worked through the pain and kept her job, but eventually it became too much to bear. The job she was trained to do in the U.S. Air Force wasn’t a good fit. For a while, she stayed home, but soon she became bored.

I, my mother’s youngest child, was already a student living at home and commuting to my small, private university when my mom decided she should go back to school and earn a bachelor’s degree.

After going through the benefits of us being close so I could help monitor her illness, it was clear that perhaps she should enroll in the same school as me. We decided to commute together and sometimes even coordinated our schedules. We’d have lunch together and shared friends.

During the three years we were classmates, we grew close but also competitive. She studied Sociology, and after bouncing around in a few majors, I finally decided to declare English as my major. We took several electives together and competed for A’s. It was fun to have her push me to do my best work and me doing the same thing for her, but then there were also the other times.

Times when she’d get a headache so bad, she could no longer stare at the computer screen. Other times, her fingers would go numb and present a tingling feeling, and I’d type her papers as she’d tell me her thoughts.

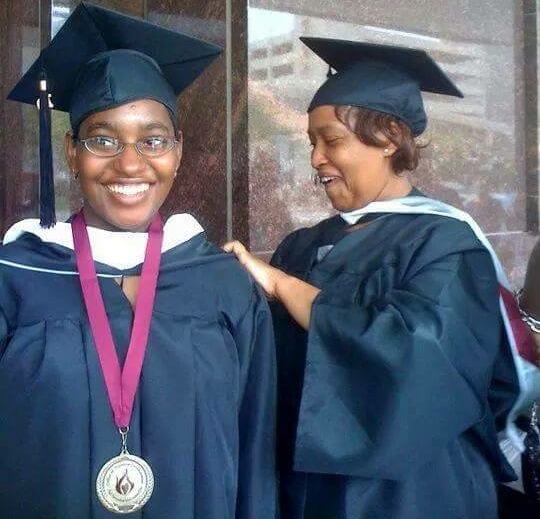

We made it through the toughest parts of college together, and it was a sight to see on our small campus. I became pregnant with my first child, which pushed my graduation date back a semester, and because of that, my mom and I ended up at the same ceremony to receive our bachelor’s degrees.

I was definitely excited for myself because my son was born six months prior to me graduating, but moreover, for me, a little black girl from the Milwaukee, to watch my mother walk across the stage — unassisted by walker or wheelchair, hell yes, you better believe — was magic.

We stood in line together, tears welling up in both of our eyes, excitedly trying to find familiar faces in the auditorium. They called her name first. I stood behind her, anxiously waiting my turn, leading the crowd in grand applause.

In the early years of my mom’s diagnosis, before hashtags, before Misty, before Viola, before Serena, I thought too that Black girls and women were just supposed to press on despite challenging circumstances without any type of recognition.

I admittedly didn’t understand all my mother sacrificed and dealt with — the stares in the parking lot because she doesn’t “look” disabled and her career as a medical assistant.

Often my mom didn’t let us see the huge struggle it was for her to get out of the bed each morning with numb legs and a severe headache. She didn’t let us pick up the pieces of plates and glasses she’d drop on the kitchen floor, always sweeping them up before we ran in.

Dr. Chavers, all of my mom’s accomplishments are magical, and I believe you, my dear, have #BlackGirlMagic to give and spread around, too.

I believe loving and living with a person with such a debilitating disease like MS isn’t always easy, so I know having the disease can’t be easy. I want to share with you something I used to tell my mom on her most difficult days: “You have MS, but MS doesn’t have you.”

Throughout the years, I’ve seen my mom’s #BlackGirlMagic develop within herself, and she leaves it wherever she goes. Graduation day was proof of that. And since earning her degree, I’ve only seen her get stronger and thrive with MS. She’s found a great employment opportunity working with youth. Every day isn’t perfect, but I see that even with a disability, #BlackGirlMagic rings louder than ever.

And you’ve got it, too. When I looked you up, I was surprised. I thought, “Wow, she’s so accomplished and living well with MS!” I encourage you to dig deep and stop downplaying yourself. Don’t internalize the fear that because your neurons don’t work like Serena Williams’ – that doesn’t mean that you aren’t or can’t celebrate you own unique #BlackGirlMagic qualities. That’s the beauty of #BlackGirlMagic, it can be whatever you want it to be, whenever you need a little boost to celebrate what makes you, you!