Here's What You Need to Know About Lyme Disease Co-Infections

Most people with Lyme disease respond favorably to proper treatment, especially when their infection is caught early. For some, however, the aftermath of a tick bite can be much worse as those little buggers can transmit more than one infection at a time.

As a result, your Lyme disease symptoms may worsen and you could have symptoms that confuse your doctor because they’re not associated with Lyme disease at all. You feel worse for longer and the usual treatments for Lyme disease don’t kick the illness as expected. The cause of your severe case of Lyme disease? It may be a co-infection.

What Are Lyme Disease Co-Infections?

A Lyme disease co-infection occurs when you contract more than one infection from the same tick at the same time. (You can also be infected with different infections from different ticks, though this isn’t always considered a co-infection.)

Lyme disease is caused by the bacteria Borrelia burgdorferi, but ticks can carry other strains of bacteria, parasites and viruses that are transmitted when they bite you. According to LymeDisease.org, since the condition was first reported in the 1980s, scientists have identified over 15 tick-related infections or illnesses that are transmitted to humans and they continue to identify more.

Co-infections are common in those diagnosed with Lyme disease. One study found that 53.3 percent of survey participants had at least one co-infection. Nearly 30 percent of the same group were diagnosed with two or more co-infections. The co-infections you’re most likely to have depend on where you live and the ticks common in your area.

How Co-infections Affect You

Each co-infection has distinct features when it presents on its own. When you combine Lyme disease with one or more of the tick-borne co-infections, however, it can be hard to tell any of them apart. They also hit your immune system much harder than a single infection, which could even overwhelm your immune system so it stops producing antibodies, making co-infections nearly impossible to detect on tests.

Wendy Adams, Bay Area Lyme Foundation research grant director, compared Lyme co-infections to having both the flu and pneumonia at the same time. You feel sicker as your immune system does double duty. In the meantime, both illnesses may interact with each other and amplify your symptoms.

In addition, antibiotics and other drug treatments rely on your immune system to “finish the job” — antibiotics can’t work without your immune system chipping in. If co-infections shut down your immune system, drug treatments and therapies may not be as effective.

“Scientists and doctors really don’t know what’s happening in the body when the immune system faces an onslaught of two pathogens at the same time,” Adams told The Mighty. “We just don’t know how co-infections change the diagnostic picture, or what treatments will work best. … Patients who go on to get sicker might be the ones who are co-infected.”

For those with “chronic” Lyme disease who have been diagnosed with a co-infection, they’ve certainly reported a difference in their experience. Mighty contributor Amy Estoye described her experience with a Babesia co-infection in her article, “How Babesia, One of Lyme’s Co-Infections, Has Changed My Life“:

The harbinger of my decline, I believe, was a protozoal parasite called Babesia. Most people don’t realize Lyme disease is caused by a bacteria, let alone that chronic Lyme is a whole army of infectious organisms. …. When I am doubled over sucking in air without relief from the feeling of needing it, when I can’t stop yawning, when my hearts jumps like a cricket in my chest or pounds like a hammer, Babesia is at work starving my tissues and organs of air.

Challenges of Diagnosing Co-Infections

Identifying tick-vectored infections is a challenge for doctors. But it’s important to identify as many co-infections as possible early on to make sure you get the right diagnosis and the right treatment. A better diagnosis, as hard as it is, leads to better health outcomes.

“A person with Anaplasma and Borrelia looks different than a person with Anaplasma and Babesia,” Adams said. “It also might confound symptoms because if you show up with five Lyme symptoms and five other symptoms that don’t look like Lyme disease, you might be misdiagnosed as not having a tick-borne infection, when in fact you have two.”

When you’re diagnosed with Lyme disease based on the symptoms you report, your doctor may use the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) test followed by the Western blot test to confirm a positive Lyme disease diagnosis. However, ELISA is inaccurate nearly half the time, so additional tests may be needed. To find co-infections, you need a totally different test called the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test. It’s usually conducted by testing your spinal fluid from a spinal tap and it can find infectious DNA in your blood.

Treating Tick-Borne Co-Infections

Once your doctor makes a co-infection diagnosis, how you’re treated will vary depending on the organisms linked to the co-infections. While there are antibiotics and treatments for most tick-borne illnesses, not all co-infections are the same. Lyme disease is caused by a bacteria. Babesia is a parasite. Powassan encephalitis is a virus.

Bacteria respond to antibiotics, but parasites and viruses don’t. You need anti-parasitics for a co-infection like Babesia. For a viral infection, the only option is supportive care. If you have more than one bacterial infection, you might need more than one type of antibiotic. It’s also a mystery as to whether treating co-infections with the same drugs used to treat the illnesses separately is the best way to attack co-infections.

“We don’t know if the same therapies are effective in the same amounts in a co-infection case,” Adams said. “For a super-infected patient, or someone who’s got more than one infection, do you need to give more medication than you would for just one infection or do you need to treat that patient differently because of the burden on the patient by being infected with one pathogen at the same time? No one knows these answers yet.”

There are many other co-infections that ticks can transfer when they bite humans and scientists continue to discover new ones. In the meantime, here are nine co-infections worth knowing more about and that your doctor may consider if you’ve been diagnosed with Lyme disease.

1. Babesia

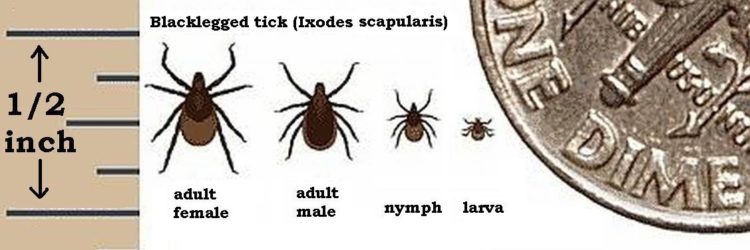

Babesia is a parasite transferred from tick to human that causes an infection similar in nature to malaria. Like Lyme, the black-legged (or deer tick) carries this infection, and according to one study, is the most commonly reported Lyme co-infection. There’s overlap between babesiosis and Lyme symptoms, but if you’re infected with Babesia, you’ll probably have a fever and chills as the first sign instead of a rash.

Other symptoms as Babesia develops could include fatigue, headache, sweats, muscle aches, chest and hip pain and shortness of breath. It’s hard to test for Babesia, and most tests can only detect two strains of the parasite despite scientists’ belief there are many more. A PCR test or a fluorescent in-situ hybridization (FISH) assay, a specific kind of lab test, help confirm the presence of Babesia.

2. Ehrlichia

Another category of infectious bacteria, Ehrlichiosis is contracted from either a black-legged tick or a lone star tick. There are a few different subtypes of this bacteria, and the most common in the U.S. is Ehrlichia chaffeensis. Ehrlichiosis symptoms range from mild to severe and even life-threatening.

The lone star tick (Amblyomma americanum) is the primary vector of human #ehrlichiosis http://t.co/H5Hoh4GnZS pic.twitter.com/QKXbjJksUd

— JAMA (@JAMA_current) September 5, 2015

Usually, you’ll notice signs within five days of being infected, such as a high fever, fatigue, muscle aches and headaches. Serious complications like kidney failure or respiratory distress have also been reported. If your immune system is already compromised by another infection or illness, your symptoms may be worse. There are lab tests doctors can order to test for ehrlichiosis.

3. Anaplasma

There’s little difference between Ehrlichia and the bacteria Anaplasma, which is considered a subtype of Ehrlichia. It’s transferred by deer ticks and western black-legged ticks. Like ehrlichiosis, you should look for fever, muscle aches and headaches, but you likely won’t see a rash. Your doctor may make a diagnosis based on warning signs from your regular blood test like a low white blood count, but Anaplasma is better diagnosed using a PCR test.

4. Mycoplasma

Originally scientists thought Mycoplasma was a virus, but it’s also a bacterial infection. The organisms are tiny. They don’t have cell walls and are undetectable with a regular microscope. Mycoplasma pneumoniae causes pneumonia, but it’s a different strand called mycoplasma fermentans vectored by ticks.

These little invaders work their way into your immune system and cause fatigue, joint pain and neuropsychiatric issues, a group of disorders that typically includes migraine, seizures, cognitive issues and mental health conditions. The presence of Mycoplasma is detected using the PCR test.

5. Borrelia Miyamotoi

Borrelia miyamotoi shares its first name with the bacteria that causes Lyme disease, Borrelia burgdorferi. That’s because both are in the same family though they’re not the same. B. miyamotoi is newer to researchers, who have found its symptoms include fever and chills, headache, fatigue and body and joint pain. However, as the infection progresses, it can lead to more severe complications like cardiac problems or arthritis issues.

6. Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever

On its own, Rocky Mountain spotted fever — caused by the bacteria Rickettsia rickettsii — is one of the more serious tick-related bacterial infections. It can be severe or even fatal if it’s not treated early on. You can get the bacteria from American dog ticks, Rocky Mountain wood ticks or brown dog ticks depending on where you live in the U.S. Symptoms include a measles-like spotted rash, fever, muscle pain and headaches. An estimated 30 percent of people with untreated Rocky Mountain fever die.

7. Bartonella

Bartonella is a tricky one in the co-infection community. Bartonella henselae, a bacteria that finds its way into blood vessels, is the bacteria behind cat scratch disease. Bartonellosis has been associated with a chronic course of illness, with symptoms like fever, a stretch-mark-like rash and neurological issues such as memory loss or balance problems. While it’s known to be carried by ticks along with other insects such as fleas, researchers aren’t quite sure what the connection is between Bartonella and tick-human transmission.

“We know that Bartonella is in ticks, it’s in a lot of ticks, but we just haven’t made that link definitively,” Adams said. “If ticks are vectoring Bartonella, then everyone needs to be assessed for Bartonella when they walk into the doctor’s office. But we just don’t have that definitive link that puts it on doctors’ radars.”

8. Powassan Encephalitis

Powassan encephalitis isn’t a parasite or bacteria, but a virus. The course of infection is often fast and fatal, causing seizures or memory loss. There’s currently no treatment for Powassan encephalitis, which is transmitted most often by deer ticks and more rarely by woodchuck or squirrel ticks. In addition to these, more potential co-infections are added to the list as more research is conducted.

Finding Future Solutions

Researchers like those working with the Bay Area Lyme Foundation focus primarily on the bacteria that causes Lyme disease because it’s the most common tick infection — around 329,000 cases are reported each year. That doesn’t mean co-infections aren’t on their radar.

Adams hopes if they can understand how Lyme works, it will open the door to a better understanding of other tick-borne diseases and their impact. That will lead to more effective diagnosis and treatment for co-infections.

“We look at Lyme as the linchpin and if we can diagnose Lyme, we will then know who may be at risk for other tick-borne diseases,” Adams said. “That’s the way we’re looking at it. Solving the challenges of Borrelia will open the door to allow us to solve all the other pathogens from a diagnostic and therapeutic standpoint.”

Header image via gabort71/Getty Images.