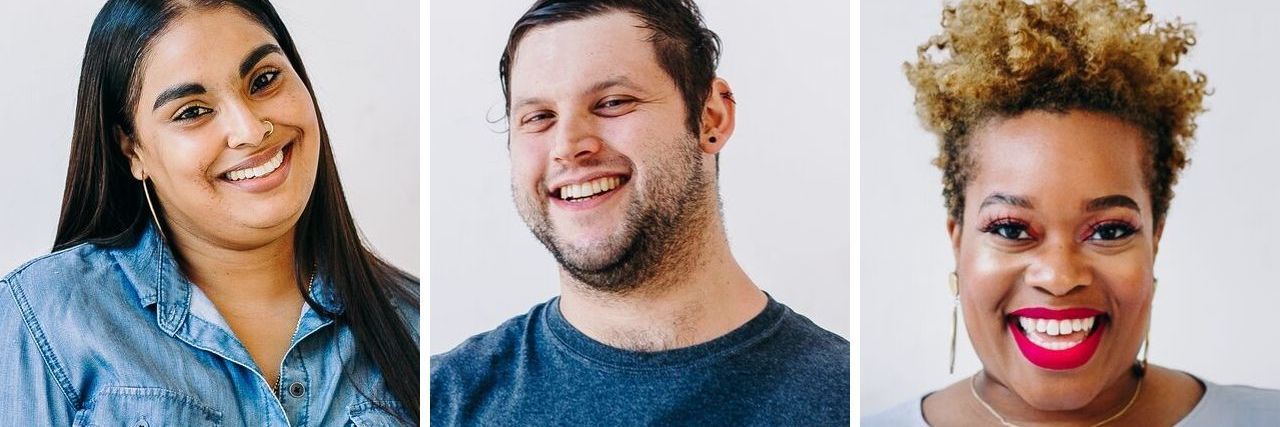

New Photo Series Aims to Break the Silence of Living With Chronic Illness

Suffering the Silence was first born out what co-founders Erica Lupinacci and Allie Cashel felt was a missing conversation around chronic illness. The pair, with the help of creative director and photographer Amanda Crommett, captured an initial “Suffering the Silence: Portraits of Chronic Illness” series. They leveraged the power of photography to start a new conversation about living with chronic illness and build a grassroots community online.

“Art & media are such powerful mediums to share stories and allow people to express themselves openly and honestly,” Lupinacci told The Mighty. “These photoshoots put a face to some of these conditions that often can’t be seen and give an inside look into what it’s really like to live with illness & disability.”

Since its launch, Suffering the Silence has focused on several initiatives such as an in-depth photo series on identity, organizing wellness retreats, hosting storytelling events and advocating for the chronic illness community through the #MarchingWithMe campaign. Now, five years in, Lupinacci and Cashel are reprising their popular photo series to celebrate the community they’ve built and to continue speaking openly about living with chronic illness.

“The stigma surrounding chronic illness often leaves people feeling misunderstood, alone, dismissed, and silenced. No one deserves to feel that way and sadly, so many of us do,” Lupinacci said, adding:

We hope that people living with illness & disability will see themselves in these photos and feel validated & understood. We hope that it will encourage them to connect with one another and share their own experience. We also want the photos to help those not living with illness & disability to see the emotional impacts of these conditions and better understand what we go through.

In the new photo series, which you can see below, Suffering the Silence’s creative director Crommett photographed nine new people living with chronic illness. The nonprofit also asked each person featured to share how connecting with others living with conditions or disabilities has made an impact on their life.

Here’s what they said:

1. Alexander

“When people think of depression, I think they often assume people have had traumatic experiences to cause depression. I come from a great family. I was always loved and supported — I was basically a spoiled kid growing up. But that didn’t stop me from struggling to get out of bed every morning. From having such extreme anxiety that it feels like the ground is cracking underneath you every ten minutes. People assume that if you have everything, that means you can’t suffer from depression. It’s like — I didn’t fit the protocol or something. And especially as a kid, that made me feel like I wasn’t allowed to struggle with this.

The heavy metal community has been so helpful for me. I stumbled into this heavy metal bar in 2016, and it was the first time I was surrounded by people who understood me. It was the first time I felt welcomed and not judged by my experience. These people didn’t care how or why I was depressed, they just cared that I was and they were there for me. I’m a journalist in music now, and just doing an interview with artists from the community and seeing how they use music to combat their demons is so helpful, seeing how these people you idolize are not that different from you. So many people are dealing with this, even if we don’t assume they are.”

2. Ali

“Because my condition looks like a stroke and has all the same symptoms of a stroke, as soon as someone sees it, they think that I am a liability. They don’t realize in a few hours that I’ll be fine again — that the symptoms are completely reversible. For the almost-ten years that I have had these migraines, I’ve been told, ‘Don’t tell people. It’s just gonna scare people.’ But then I get in these situations when I have one and nobody knows what to do. I can’t talk, I can’t do anything — so then what am I supposed to do?

I’ve gotten to a place where whenever I’m in a new situation, I find one person and just kind of confide everything in them. So that way, if something does happen, I know I’m okay. I started doing this really when I stopped drinking. That made me realize, oh shit — I can’t hide this anymore. It made it so that I had no choice but to say, I have this. I live with this.”

3. April

“Because you can’t tangibly see my condition, it makes it even more hard when you are explaining that you don’t feel well. With my hair and makeup, you can walk in and out and go to work and carry on with your day-to-day life but if you’re like ‘Hey, I’m having a bad day’ it’s like, ‘Where?’ Dealing with the stigma of people actually believing what you’re saying other than ‘I’ll believe it when I see it’ has been the most troublesome thing of dealing with a silent chronic condition like Endometriosis. You’re never gonna see it, you’re never going to experience and understand what I go through unless you either have Endometriosis or another chronic condition.

I felt powerless when I was first diagnosed with Endometriosis and then I had a surgery thinking I was cured and then 10 months later, I had a second one. So my whole method behind me being an advocate is I never want anyone to feel isolated and alone like I did. So if I can at least touch one person with my stories and they don’t feel like they’re by themselves, then I feel like I’ve helped.

The endo community is its own unique form of sisterhood, which I absolutely love. It could be my first time seeing you and it’s like we have this bond because you are my endo sister. And you gain strength and power in numbers — it’s one thing if you have family and friends to support you, but to have someone who actually empathizes with you, someone who is actually going through the same exact journey as you, is a different connection that no one else will understand unless you have that same condition.”

4. Charles

“I joke that I have a big mouth and I think when I got diagnosed, I decided it was one of the things that kept me alive when I realized — maybe I can be the example. Because I do have a big mouth and maybe I can be that person with HIV who is healthy and okay and opposite of what we think of when we think of AIDS. The stigma — how it’s affected me has been really subtle, I’ve been really fortunate. My family knew I had AIDS because I almost died and they had to make decisions for me. So I didn’t have that dramatic coming out with HIV to my family, I didn’t have to do that.

When I found out about U=U a few years back, I had no idea. I was like, ‘Wow.’ If my viral load has been undetectable and I won’t transmit the virus sexually, and I haven’t because I’ve been undetectable for almost all the time since I got out of the hospital 16 year ago. So all that time, I have not transmitted the disease. It made me feel more healthy, more alive, responsible, that I didn’t even know that I felt opposite about myself. I own that I had self-stigma.

It’s challenging because I think there are so many aspects of the community that are based in the fear of the ’80s and ’90s. The first thing that we think of when we think of HIV & AIDS are images of those people that had Kaposi Sarcoma, who were super skinny. That’s one of the things that I’m fighting against. There’s a group of us that are collectively trying to fight that older narrative.

One of the most powerful things that was ever said to me about stigma was from @Kenlikebarbie. He said, stigma is oppressive to the point that it kills. And when I heard that, it hit me, it really can be smothering and it can make people hide so far into themselves and into their own worlds that they wither away or stop taking care of themselves. I am opposite, I am fighting back, I am pushing back, and I’m going to bring everyone else with me.”

5. Devri

“There have been moments throughout my journey where I feel like I’ve been muted, and not by choice. I am a very vocal, forthcoming, straightforward person. I like to speak my truth. But I have been in spaces, particularly with dating or living situations, where I haven’t been taken seriously enough or have scared people away. I can’t wait until a crisis happens for people to understand the severity of what I’m going through. It can be challenging to power through and get to the bottom of what is going on with me, but I always try and do it. I try to give people a fair chance to make a decision about whether or not they want to enter this life with me. Because it can be a lot, it can be overwhelming. Sometimes I feel like I scare people off because I am so honest about what is happening with me. I often feel the urge to silence myself, but I don’t — because I have to let people know what’s going on.

The most important thing, and what touches me the most is when people ask me how I’m feeling. It just opens up my heart. It can be a stranger, it can be a close friend. I’ve had people who follow me on Instagram and they’ll see me out in the neighborhood or at the park and come up and say, ‘How are you feeling today?’ It’s just so beautiful. It’s such a human thing to check in on someone. We can present ourselves in such a way that makes us look like we’re OK — which is something I do regularly — and it’s hard to tell how people are doing with invisible illnesses because they are invisible. So it’s really important to check in. And when someone does it, it just makes my day.”

6. Leah

“I’ve had doctors dismiss my symptoms as being ‘all in my head.’ At one point I was having severe tachycardia — something that I cannot physically lie about. I went to the emergency room and I begged them to admit me because I didn’t feel safe in my own body. They did an EKG and an ultrasound on my heart. When they couldn’t immediately find anything physically wrong, they of course sent psych in. Psych told my parents that they thought I was making it all up, that it was all in my head. I just felt like they were dismissing me, dismissing my symptoms, and trying to make me go away. They were trying to make me be quiet. I remember I just started crying, there was so much emotion, I couldn’t hold it in. I felt frustrated, and angry, and also kind of defeated. I wanted to just give up. If they don’t believe me — what can I do then?

The fact that my parents have always believed me and supported me, made me feel like I could go on. I knew we could fight this together. Most recently, my Lyme disease has started manifesting itself psychiatrically and I’ve been experiencing a lot of OCD. I feel crazy a lot of the time, but my mom never makes me feel wrong or crazy for anything that I am experiencing. Sometimes I feel wrong. Sometimes I look at myself and I see myself the way those doctors saw me. My mom has never looked at me that way.”

7. Pam

“When I first got diagnosed in 2012, I lost so many things. I felt trapped, and I didn’t know who to talk to about it because I was just learning about it myself. I thought people didn’t understand what I felt or thought because I looked fine. But internally, I was falling apart. I was so quiet. I guess I was just dealing with it myself, because even when I did speak about it, I didn’t get the response or support what I was searching for.

Then I met other people with lupus, and I was like, ‘You guys get me! I need to stick with you guys.’ They’ve helped me get myself back. I lost everything because of lupus in 2012. But lupus is what gave me everything I have today. I lost my job. I couldn’t go to school. The hospital became home. I lost my self-esteem. I lost my hair. But lupus, and the lupus community, also gave me that push. I decided I was going to go back to school. I got my master’s. I’m a teacher. I got my hair back. I feel almost like — I can’t let the other Lupies down. If I can do something, they can do it too.”

8. Sam

“I have felt silenced my entire life. I have a disability that affects me both physically and intellectually, but most people don’t see it because it’s ‘mild.’ This has made me feel a lot of guilt and shame about asking for help, even though I have very legitimate needs and accommodations. As I get older, I’m learning the importance of asking for help and not feeling guilty about it.

Something that has been essential for me in order to feel more comfortable with being true to myself and my needs as a disabled person has been surrounding myself with people who accept me for who I am, both my good and bad traits, on the good and the bad days. It’s been a lifelong process that I still struggle with and I honestly feel like I’ve only just begun to make headway on it. But if you’re persistent, show yourself some compassion, and don’t give up, those people will lift you up and help you figure out who you really are, even if they don’t realize that they’re doing that.”

9. Tina

“I was diagnosed 13.5 years ago but I feel like for a long time I kept it quiet. It’s so deeply stigmatized in American culture. Crohn’s being a bowel disease makes it very difficult to talk about. It has to do with something that nobody talks about. It’s so debilitating. A lot of times it’s mistaken for an eating disorder because our weight can be all over the place so nobody wants to ask us what’s going on because they’re ashamed to. We want to be asked how we’re feeling.

Since I became an advocate, more and more people are asking. People are understanding the different nuances, the different surgeries, because I talk about it all the time. I never realized how many people have this condition until I started talking about it. I have a lot of people all over Asia reaching out because I look like them. Just having someone who dresses like you, presents like you — makes a difference. They look to me for the Indian aspects, the Pakistani aspects, the Middle Eastern aspects of this disease. There’s a lot of cultural issues that go into it — how do we talk about this disease and all of its nuances if even our friends don’t get it and we are afraid of being made fun of for our bathroom issues? You’re not supposed to have kids because you have disabilities. People just assume that just because you have a disabled identity, there’s no sexuality. There’s no marriage ability to a person, you don’t lead a normal life. You do, you do. People ask, ‘How can you still get married?’ Be honest from the beginning, talk about it. If they don’t accept you, they’re not the right person for you. It is possible and it does empower people to see that.

I also have an ostomy bag and that adds a whole other layer of silence to all of it. Having a fistula, I’ve had several of them. I put out articles on that — my experience, the psychosocial aspect, the impacts on our marriage. These are really taboo subjects but people have to talk about it. We suffer in silence but I think you’re allowed to have an identity of suffering and of disability and be allowed to commiserate with other people and support other people and empower them at the same time. I think there’s beauty in imperfection and I think that needs to be highlighted.”

Visit the Suffering the Silence website for more information.

Header image via Suffering the Silence/Amanda Crommett