How Our Daughter Helps Us Face Our Greatest Fear

When possibility becomes probability, then certainty-barring-a-freak-

Last week I posted a conversation my daughter, Julianna, and I had about heaven. Sharing something so deeply personal doesn’t come naturally. That conversation took my breath away, and I felt like I had to share it. I’m grateful to those who expressed their good wishes and admiration for our Julianna. Others found my questions “leading” and questioned the value I place on life. I’ll admit, those few comments hurt. Like any mother, my biggest vulnerability is my children. Children are supposed to outlive their parents.

I realize that the idea of not doing “everything” to prolong the life of a young child is perhaps unacceptable to some. But when your child’s illness is terminal, when the disease takes more and more and the treatments become riskier and offer less return, there are choices. The choices seem impossible, and they’re painful. We believe that sometimes it’s an act of love not to do “everything” to extend life and focus instead on giving your child the most beautiful life possible for as long as you’re allowed.

Julianna has severe neuromuscular disease. Problems with swallowing and breathing are things that kill people with neuromuscular disease, and Julianna started showing signs of these issues before she turned 1. She had three separate PICU admissions (63 days total) for respiratory failure in 2014. It was our annus horribilis.

The mainstay of her hospital treatment was aggressive “pulmonary toilet.” This is a multi-step, uncomfortable procedure, and involves naso-tracheal (NT) suction. The respiratory therapists (RTs) placed a catheter in her nose and guided it back into the throat. They tried to make Julianna open up her glottis by coughing, then they accessed the first part of her trachea and got the stuff she’s too weak to cough out on her own. It was torture for Julianna. Too weak to produce sound, she would cry silently — but she endured it again and again. The treatments took about an hour and were done every four hours around the clock or sometimes more frequently. Our Julianna was valiant and did everything that we asked her to do. The RTs were amazed by her courage. I knew that part of the reason she complied so well was because she was too weak to do otherwise. It is an exquisite form of torture, not being able to trade places with our children when they’re in such pain.

Julianna used to be able to walk short distances in a walker and use her BiPAP (noninvasive ventilation) only at night. By the end of the third hospitalization, she had difficulty sitting up even with support and could only come off of BiPAP for a few hours at a time. During this third hospitalization, we discussed her code status, met with the palliative care team and had a care conference. No one could give us a timeline, but everyone agreed that, at one point, the BiPAP would not be enough. The next step would be tracheotomy and ventilator dependence. I can’t get into the agony of contemplating this question in this space. Though we didn’t need to make a decision immediately, my husband and I agreed that it would probably not be the right choice for Julianna.

The palliative care team talked to us about hospice. We learned that hospice is not just comfort care, and it could be revoked at any time. This last part was very important to me. If Julianna got sick again, we planned to go straight back to the PICU. The treatments were agonizing, but maybe it would give us more time with her.

When I met with the hospice nurse, I emphasized the fact that we wanted to go the hospital if Julianna got sick again. She nodded and said that we could do this. I told her that I couldn’t let Julianna die at home — it was too scary. She nodded again and said that many people who enroll in hospice start out that way but later change their minds. Part of the process, she said, was “becoming comfortable with the uncomfortable.” I didn’t really buy it, but I liked the fact that she understood our concerns. She also told us she was available to us 24/7 if we had problems with Julianna. She would come over if needed. We decided to give it a try.

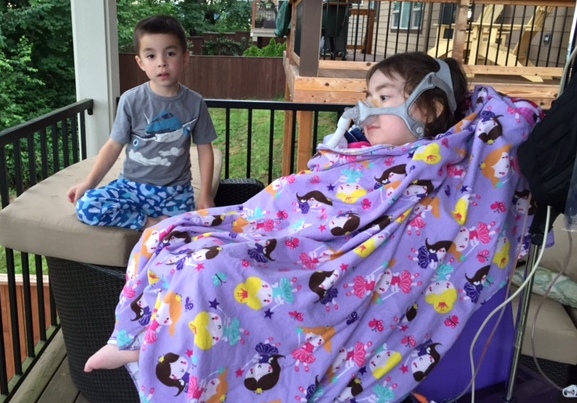

Hospice gave us many immediate benefits. We have almost instant access to medical advice via our hospice nurse. Twice a week, an aide comes to give Julianna a bath. A bereavement counselor meets with Julianna and our 6-year-old son, Alex. We had no idea how to start preparing Alex for the inevitable. The counselors helped us start the conversation. We also got paired with a volunteer. Our hospice angel visits Julianna every Saturday morning. She gives her four solid, continuous hours of playing and talking and singing and reading. One of the hardest things about Julianna’s disease is the isolation. Our daughter loves people and wants to make them happy. This team of hospice helpers has helped expand Julianna’s world — more people to love and give love.

Julianna’s medical routine hasn’t really changed. We still do her respiratory treatments, give the same medications and maintain the same feeding schedule. Her disease has continued to progress. When we started hospice in November 2014, she could come off BiPAP for about two hours at a time. She is now completely BiPAP dependent. She has also lost almost all use of her arms. It’s painful to witness the regression of your child, but now my focus is different. I am no longer consumed by doing everything I can to work against Julianna’s disease. It is easier to give her my undivided attention and just enjoy her. I think that Julianna senses this, and it has helped her thrive.

It has also started some difficult but amazing conversations. Most of these take place as I’m sitting by her bed at night, waiting for her to fall asleep. Julianna talks about the hospital — a lot. Usually about how much she hates it. I tried to remind her of all the wonderful people who helped her. We hate all the NT and pokes too — but they killed the germs and let her come home, so didn’t that make it OK? We had this conversation many, many times. Julianna wouldn’t say anything, One night in early February, she finally answered. She said “no.” And then she started talking about heaven.*

Tears started rolling down my face, and I was glad that the room was dark. We had taught Julianna our belief that there is a better place for her. In heaven, she will be able to walk, jump and play. She will not need machines to help her breathe, and she will be able to eat real food. There will be no hospitals. Very clearly, my 4-year-old daughter was telling me that getting more time at home with her family was not worth the pain of going to the hospital again. I made sure she understood that going to heaven meant dying and leaving this Earth. And I told her that it also meant leaving her family for a while, but we would join her later. Did she still want to skip the hospital and go to heaven? She did.

The next day, I talked to my husband, Steve. More tears as we rethought our choices. Between us, I was always more adamant about going back to the hospital. I had a deep fear of bringing the pain of the PICU to our home, but we both felt that we had to honor Julianna’s wishes. We agreed that we would continue to talk to her about this. If she changed her mind, so be it. Our plans became plans “for now.”

We then talked to our hospice nurse. Julianna’s wishes were too clear to ignore — but how much can she really understand at age 4? Do kids who are at the end of their lives know what’s coming? How would we make sure Julianna wasn’t in pain at home? Our nurse cried with us and told us she believed children with terminal illnesses do understand death. They may not understand everything about it, but who really does? She told us about other children in hospice who talked about seeing angels in the days before they passed. She went through the most likely scenarios, and what could be done to make it as easy as possible.

We have had more conversations, mostly initiated by Julianna. She’s scared of dying, but has, to me, demonstrated adequate knowledge of what death is. (J: “When you die, you don’t do anything. You don’t think.”) She hasn’t changed her mind about going back to the hospital, and she knows that this means she’ll go to heaven by herself. If she gets sick, we’ll ask her again, and we’ll honor her wishes.

During that last hospitalization, the PICU team asked for a psych consult — standard procedure for kids with multiple hospital admissions. They found Julianna to be well-adjusted and happy. She knew her situation but was OK because she felt safe and loved. It was really her parents who needed the help. I talked to them about some of the impossible decisions we faced. Was hospice an attractive option because I was so, so tired? Was I thinking of it as an easy way to end all of our pain?

The psychologist looked into my tear-filled eyes and said with sadness, “There will be pain with whatever way you choose.”

Our months in hospice have been stable and wonderful. We’ve been given a second chance to enjoy our Julianna. I’m still scared of what is to come and can’t really imagine life without my baby girl. I know that this won’t last forever, but I’m grateful for the time we have now.

*Author’s note: While going through e-mails in preparation for Julianna’s blog, I discovered that our very first conversation about heaven was actually recorded. I regret that this part of my story was inaccurate, but I am very happy to have Julianna’s words. She was clear and unequivocal. You can find the first conversation here.

RELATED: My Daughter Wants to Choose Heaven Over the Hospital