Author’s Gripping Account of Her Son’s Condition Challenges How We View Mental Illness

Randi Davenport is a writer based in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, and her story is one that parents of children with mental illness may recognize. Her son, Chase, diagnosed with autism, began showing signs of a serious mental illness by the time he reached age 14. He suffered horrifying hallucinations, became violent toward himself and even stopped recognizing his own family members. As Davenport sought treatment for Chase, doctors and specialists repeatedly told her they’d never seen anyone like him and didn’t know how to treat him. It became apparent that no one could help him.

Randi Davenport is a writer based in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, and her story is one that parents of children with mental illness may recognize. Her son, Chase, diagnosed with autism, began showing signs of a serious mental illness by the time he reached age 14. He suffered horrifying hallucinations, became violent toward himself and even stopped recognizing his own family members. As Davenport sought treatment for Chase, doctors and specialists repeatedly told her they’d never seen anyone like him and didn’t know how to treat him. It became apparent that no one could help him.

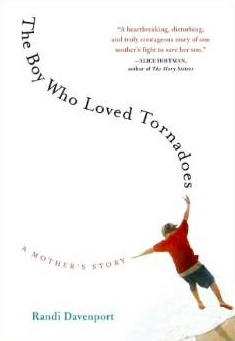

Written with courage and unwavering love, Davenport’s memoir, The Boy Who Loved Tornadoes, tells the story of her family’s experience with mental illness and developmental disability. It gives voice to families who have endured similar struggles and had nowhere to turn. The Mighty had the chance to talk with Davenport about her writing process, what she learned about the mental health care system in the U.S., what she feels must be done to fix it and how everyone can help reduce the stigma our society has against mental illness.

Can you describe the moment when you first knew you had to write this book?

I never set out to write a book about my son’s illness. But in 2003, I was aware of a heated conversation about mental health reform in North Carolina, including everything from substance abuse, instability and mental illness. Policy makers were making their opinions known in the press about what had to be done, and I noticed there were no parents [of people with mental illnesses] making their voices heard. I decided to write a column for the local newspaper, and I’d written 100 pages when I realized this was more than a newspaper column. I still didn’t call it a book; that was too overwhelming. I don’t think I could have done it that way. I called it a project. I was doing it to offer something to the larger public, and I wanted parents’ voices to be heard. But when I’d written 600 pages, that’s when I realized I was writing a book and began to shape the pages into a manuscript.

How old was your son when he began showing signs of a psychiatric illness, and how did you initially go about getting a diagnosis for him?

Chase began showing signs of psychosis at age 5 or 6. I took him to a child psychiatrist at a large teaching hospital in the midwest, and the doctor told me he thought Chase had atypical autism. When Chase went to hospital again at age 14, after showing more serious signs of mental illness, I asked that same doctor again what he thought it could be, and he told me he always thought Chase had childhood schizophrenia but didn’t want to say so at the time because it’s such a scary diagnosis. Chase does not have schizophrenia, but the psychiatrist should have been straight up with me from the beginning.

For much of the book, specialists were unable to diagnose the more serious psychiatric disorder that emerged when Chase was a teenager. How did this affect his treatment plans?

Chase is 27 now, and we still do not have a diagnosis. I was tasked with finding a place for him because everyone said he would need 24-hour care for the rest of his life. No doctor had ever met anyone like Chase, who had multiple symptoms that don’t lead to clear diagnosis. He hadn’t responded to anti-psychotics but insurance rules dictated that he couldn’t stay in the hospital indefinitely — nor was this the best place for him. Because he had competing diagnoses, residential facilities focused on one or another of the different treatment modalities (developmental disability, mental illness, substance abuse) couldn’t or wouldn’t take him

You and your family had to clear quite a few hurdles to find adequate treatment for Chase. Throughout that process, what did you learn about the mental health care system in the U.S. and in North Carolina specifically?

We lived in New York when Chase was little, and there was nowhere to turn to specifically to get him help. When we lived in the midwest, there wasn’t much there, either — we had the opportunity to have him removed from my house for a weekend, as a way to give us a break for a couple days, which seemed more like a punishment to me than a treatment plan. When Chase required intensive help, I quickly learned what was and wasn’t out there. Mostly, there wasn’t much. And things have only gotten worse since then. Funding for mental health has been slashed in this state, as it has been across the country. Hospitals have closed. There’s very little in the way of community housing for people with mental illnesses and many rural NC counties no longer have a psychiatrist in them. If you live in a rural county in North Carolina and have a mental health problem, you’re going to have a hard time getting help. Even families in the comparatively better-off part of the state where I live struggle to find the services they need. And just as my challenge was once finding long-term residential care for Chase, now that’s he’s done so well and needs to move to the community, I’m battling to find housing and services for him once again.

How much do these shortcomings you’ve described in the mental health care system have to do with the stigma our society has against mental illness?

Despite the fact that many families in this country are going to deal with serious mental illness at some point, the stigma attached to mental illness remains. As a culture, we still tend to view the mentally ill as suffering more from a moral failing or a character flaw than from a disease of the brain. I’ve even met parents who are very angry with their family member for getting sick and wish they would just snap out of it. And just think of the proliferation of horror films featuring a mentally ill villain–in these, mental illness becomes closely associated with extreme violence and the paranormal. Such representations enforce the idea that mental illness belongs to the evil.

How were you eventually able to find adequate treatment for Chase?

He now lives in the BART (Behaviorally Advanced Residential Treatment) unit at the Murdoch Center [in Butner, North Carolina]. It serves young men with dual psychiatric and developmental diagnoses with extreme behavioral problems. Most residents have a long history of failed placements and a history violence or crime, so Chase is different from most of the people who live there. But it’s worked well for him.

Can you describe a moment when you knew your book was helping others?

Oh, there have been so many. It was a very isolating period, when I was raising Chase. I began to connect with other people going through something similar experiences when I did readings in bookstores and on the radio. For people who do get it, it’s emotionally resonant. During a radio reading in Minnesota, a woman actually pulled over to the side of the road to call in and say, “You’re describing my son, you’re describing my life, you’re describing everything we’ve been through.” I still get emails every once in awhile from people who have had that “Oh my God, you’re telling my story” moment. I still get messages on the book’s Facebook page. There’s a lot of powerful sentiment.

How have your lives changed since your book was published in 2010?

If I were writing the book now, the ending would be: Chase is currently living without a trace of psychosis, he is holding down sheltered employment, he is working on his GED and he is ready to move from the institution where he’s lived for the past 11 years.

I published my second book last year, The End of Always, a novel that draws from a historical record of a mystery surrounding my great-grandmother’s life. One of the novel’s characters is similar to Chase, and I paint him in a much more positive light than how people with mental illnesses are typically portrayed.

How do we de-stigmatize mental illness?

I wish that every single person who encounters someone with mental illness would take a few minutes to get to know that person. They would then understand that that person is first and foremost, a person.

What advice do you have for families going through similar experiences to yours?

Don’t lose hope; you’re stronger than you think you are.

Want to celebrate the human spirit? Like us on Facebook.

And sign up for what we hope will be your favorite thing to read at night.