Deciding When Not to Treat Our Child With a Degenerative Disease

In most areas of my life, I prefer to regret something I have done rather than regret something I haven’t done. But when it comes to my 6-year-old son with Menkes disease, this — like so many issues — doesn’t fit the norm. When you face a degenerative disorder in your child, a lot of measures get turned on their heads. The expectation can’t always be to make things better since we know the longterm path involves things getting worse. Things are going to stop working as they should. So how do we decide which of those things are preventable or can be stalled, and which medical interventions are not worth the risks?

Recently the problems with Lucas’s hips and spine went from minor to severe. The hip that would chronically dislocate was now permanently dislocated, and the previously normal hip was chronically popping out of place. His spine curvature had greatly increased, and we began to fear his positioning due to a question-mark-shaped spine might compress his internal organs.

Two surgeries were recommended: one for the hip(s) and then later for the spine.

Most parents think they’d do anything to help their child. My wife and I think so, too. But we had a gut feeling that maybe the treatment would be worse than the problem it would fix.

We think Lucas has a diminished sense of pain; he rarely complains from any discomfort. Maybe his nerve receptors are under-developed along with his brain, muscles and bones. (If so, what a welcome silver lining to this horrible disorder.) So his hip, despite being visibly “wrong,” wasn’t uncomfortable to him. He doesn’t walk, or sit unassisted, so he doesn’t absolutely need the hip to function normally. As for the spine issues, we checked in with his specialists and each told us that so far, it wasn’t impacting the function of his organs. The curve happens low on his spine, so his lungs, bladder and kidney are all so far so good.

If Lucas was constantly crying out in pain, we might have rushed him into surgery. But the surgery recovery can be long for patients in normal health. Lucas tends to recover three times more slowly than normal. For a child expected to have a short life, did we want him to have several months of it spent in hospitals?

Add in the risks of any surgery — maybe it goes badly, maybe an infection sets in — and we were not just afraid to move ahead but also questioned the value of these interventions. We didn’t want to kid ourselves either. Would we stick our heads in the sand and hope for the best despite being told things would get worse? But by now, we take it as given that some things will eventually get worse. Should we fight to stave off all of them?

We did not decide this lightly. We switched our insurance so that we could visit other doctors at a different hospital for additional opinions. We drove hours and spent nights away from home to make those appointments. Some doctors said yes, some said no to surgery. Many more remained neutral, reminding us it was our decision.

Lucas can’t talk, so he can’t tell us his choice with words.

What haunted us (and still does): would we kick ourselves more if we did nothing and eventually saw things get worse, or if we did the surgeries and things got suddenly worse?

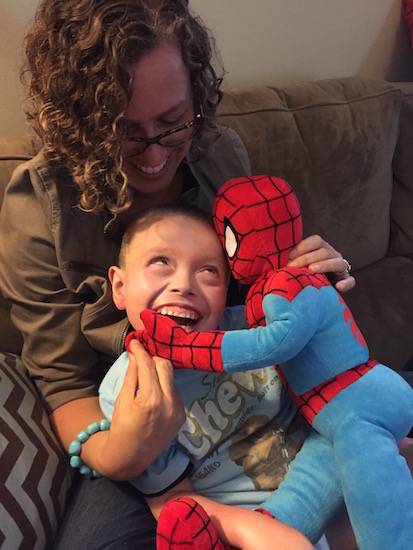

We have been extremely fortunate that for nearly two years, Lucas has been in great spirits and good health (his version of good health). He’s had nothing worse than common colds and flus to contend with if you discount the hip issue. Hospitalizing him, with risks of aspiration or ending up with a tracheotomy, seemed so much harder a decision given how happy he’s been lately. I began to imagine an outcome where we’d trade a bad hip he didn’t really need for a bad windpipe he really does need. If fixing the hip left him with a trach, was that a good trade-off? Was that progress toward a healthier boy? Never mind that the day will likely come that Lucas does need a tracheotomy; I just didn’t want to cause that day to be tomorrow.

We wrestled the pro and cons back and forth for several months, gathering more medical advice along the way. Eventually we both found some peace in the decision that doing less would help him more. Early on after his diagnosis, my wife and I decided we wanted greater quality of life for Lucas, not necessarily greater duration of life. We also told ourselves “no extreme measures.” The catch there is that those measures creep up incrementally and don’t often seem extreme in the moment. Sure enough doctors tell us this surgery is a risk but not an extreme measure; they do it all the time on kids more fragile than Lucas, too. I believe that. But “extreme” is still subjective. A day may come when we face more pain for Lucas and regret not intervening earlier. Maybe by then it will be too late to attempt some of the options for treatment we have now.

Deciding not to “help” our son has tormented and terrified us. But watching him live each day pain-free and happy, we can’t take the chance of changing that. Not today anyway. As always we’ll face tomorrow, tomorrow.