What My Uncle Taught Me About Violence and Mental Illness

There has been a lot of talk about mental illness lately. It comes up in the wake of any major shooting to explain the assailant’s actions. They were crazy, people say. Insane. Unsound. Even when the people are competent to stand trial.

It’s an approach I hate. I believe to use mental illness as the sole explanation for a mass shooting is a profound oversimplification that absolves us of the guilt our inaction has caused. It screams in the face of facts; it ignores empirical evidence.

Most of all, it does a disservice to those for whom it supposedly speaks. Nothing stigmatizes mental illness more than branding all killers as crazy and unstoppable, and throwing up one’s hands because there’s nothing that can be done about it.

I believe it’s not a mental health issue. At least, not exclusively (because the argument can be made that anyone who kills another human being is, in fact, mentally disturbed. And some of these shooters are not competent to stand trial). It’s also an issue of violence, of gun control and of our refusal to do anything to change a status quo where mass shootings seem to happen more often than Nordstrom has sales.

And every time someone says, “It’s a mental health issue,” and has never, before or since, cared about mental health, I find myself wanting to scream.

Because here’s the thing: I grew up around people who were mentally ill. And I grew up around people who were violent. And I can tell you: the two do not go hand in hand.

People with psychiatric disabilities are far more likely to be victims than perpetrators of violent crime. People with severe mental illnesses, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder or psychosis are 2 ½ times more likely to be attacked, raped or mugged than the general population.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services paints an even grimmer picture: people who have mental illness are 10 times more likely to be victims of violence than the general population.

And the percentage of mentally ill people committing gun crimes is actually less than that of the general population.

I know mental illness well. I know it because of my own battles with extreme anxiety. With my husband’s bouts of depression he’s written extensively about. Through my wonderful friends who’ve bravely dealt about their own illnesses. (Because screw stigma.)

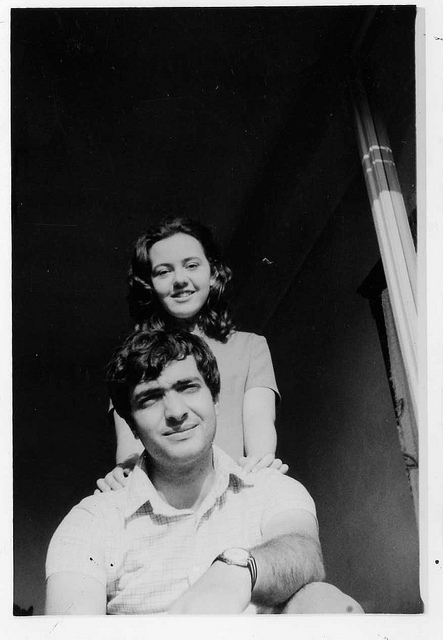

And I know it because of my uncle.

He died a decade ago. Throughout my life he lived with us, along with my grandparents, starting when I was very young, in a craftsman style house in northwest Seattle. I thought it was the most beautiful one on the street. I’ve driven past it in recent years, and I still think this is true. It might just be because my memories there, of people now long gone, are happy ones.

As the dissolution of my parents’ marriage coincided almost perfectly with my birth, my uncle helped to fill the father-shaped void in my life. He walked me to the local mini-mart and bought me candy and wind-up toys that would break almost instantly (or that never really worked at all). In my very early years, I spent countless hours with him.

He was patient and funny and endlessly doting.

I remember the day my mother pulled me aside to explain that he was sick. I must have been 3 or 4. A narcissistic little kid with little besides self-preservation on my mind, my biggest concern was whether or not I could catch it. I didn’t want to lose my playmate and candy dealer, the only person who let me blow bubbles in the house. When my mother explained it wasn’t contagious, I bounded back into my playroom and gave it little more thought.

Over the years, I would come to understand that my uncle’s illness was not the kind you could treat with rest and soup. That it made him different from other people. It was the reason why he did not drive, or hold a job, or cook, or clean, or date or ride a bicycle. He had conversations with people, but they consisted mostly of his proclamations and their bewildered responses to him. He smoked constantly, twitched and paced the house for hours, talking to himself or flicking his nicotine-stained fingers. Sometimes he would sit, staring at nothing, shaking with raspy laughter. If he forgot to take the bevy of medicines prescribed to him, his gestures would become more erratic as his hallucinations became more vivid.

My aunts and mother occasionally asked him about the things he saw. He once said the wall looked like a giant pair of hands knitting a scarf. This was one of the more innocuous visions. I heard hushed whispers of the other things – terrifying things – that entered his mind. Demons, monsters, spectres. He never burdened me with it, and I was too young to ask. Besides, I didn’t really want to know.

He occasionally thought he was God (one episode coincided rather comically with a pair of missionaries knocking at the door; my mother just sat back and watched it unfold). One time he thought he was Caesar. Another time, Napoleon. He was constantly telling me he was telepathic and that later he’d talk to me with his mind. When I was very small, I tried to concentrate to see if it would work. But as the years progressed, my face would burn with shame whenever he mentioned it.

We grew apart as I grew older. I was embarrassed by him. By his lack of hygiene, by his overwhelming, all-consuming illness. There was no semblance of “normal” about my uncle. By the time I was in high school, the opinions of my contemporaries held a disproportional amount of sway.

“Is that, like, your relative or something?” a friend once asked.

“Yes,” I said. I didn’t elaborate.

We lived under the same roof. I ignored him, offering up a quick hello whenever we crossed paths, and little else.

Towards the end of his life, after decades of smoking and anti-psychotics had taken their toll, he thought we were poisoning him. That his physical symptoms were a result of the things we had done. He yelled at my mother and my grandmother often. Once, and only once, he yelled at me from a hospital bed. Nearly blind from diabetes, barely able to walk, he told me to get out; that he knew I was behind this.

I wasn’t angry. I wasn’t even upset. Just surprised. It was the first and only time he’d ever raised his voice to me.

My uncle was many things. Intelligent, generous and kind. He also had severe schizophrenia. He was not violent, not even when the voices in his head convinced him we were slowly killing him. He rarely yelled. He never threw anything, never tried to hit anyone. He never even slammed a door.

He thought we were murdering him and he still loved us.

There is a difference between violence and mental illness. I know. For 20 years, starting from the time I was 5 years old, my mother was in a physically, verbally and emotionally abusive relationship. Every door to every bedroom I had would be reduced to splinters by a man who vacillated between fun and rageful. He would trash my room, throw my possessions down the stairs and destroy things I loved. Dishes would be broken, parts of the wall reduced to crumbled sheet rock. He would scream hideous names at us. I would try to do my homework, listening to his wrath as it spread across the house, wondering if it would come crashing through my door.

Despite this, I believed my mother when she said she fell down the stairs or walked into a wall.

He weighed more than she and I together. I lived in panic. I didn’t sleep through the night until I left for college. I spent my waking hours studying in order to secure a scholarship and on-campus housing.

I know mental illness. And I know violence. I can tell you definitely: the two do not always go hand in hand. My mother’s partner was, by all accounts, sane. He could drive and hold a job and chaperoned me on school field trips – all things my uncle never did.

He also called me horrific names and terrified me. He carved deep gouges in my bedroom walls and in my childhood. All things my uncle never did.

I can tell you which one was “crazier”. And which one was more dangerous. And which one owned a gun.

Last week, there was another mass shooting, this time at a Planned Parenthood clinic in Colorado Springs. And this week, another — at the Inland Regional Center in San Bernardino, California.

Once again, a bevy of temporary mental health advocates emerged from the woodwork, claiming that insanity was the problem.

Nearly every day, my uncle is grouped with cold-blooded killers and murderers. My mother’s ex, who exhibited characteristics far more in line with any of these shooters, is not. The NRA wants a database of people who are mentally ill (and a majority of states have created just that). But we don’t want a database of gun owners. Register your vehicle and your sick uncle, but not your weapon.

I don’t want this to turn into a second amendment debate. If you want to keep a weapon, that is, much to my chagrin, your right as an American. If you don’t want a registry, or more gun control, then say that. Say that you don’t want to give up your right, and you are willing to sacrifice the lives of innocent people in order to have it.

I don’t agree, but I’ll at least respect your honesty.

But, please, stop saying there’s nothing we can do to stop it. Stop arguing it’s a mental health issue. Because every time you say that, it illustrates precisely how little you care for people with mental illness, and how easily you are willing to demonize them to justify your own views.

Follow this journey on The Everywhereist.