Dear Teachers and Therapy Team:

It’s the beginning of the school year, and we’re so glad you’re a part of my son Evan’s team. Navigating preschool was a road of trial and error, and I expect it to be very much the same as he enters his kindergarten year.

Evan is more like his typical peers than different, with his own strengths and challenges. Just like every other child, it will take a little time for you to get to know Evan, and it will take us a bit of time to learn how things work in elementary school. We don’t expect everything to go perfectly right from the start, and we know we will all learn together. I hope this letter will help, and I hope you know we’re always willing to communicate and listen.

As you probably know, kids with Down syndrome have a whole or partial extra copy of chromosome 21. Each child with Down syndrome is affected differently by that extra chromosome. For Evan, it means low muscle tone, coordination issues, fine motor issues and challenges with regard to speech. But it also means determination and persistence when there is something he really wants to learn. When Evan is learning new skills, he may try them 10 times until they come naturally. It’s that determination that we believe will make him successful in school.

On the other hand, Evan can be very creative in his escape behaviors when something is very challenging for him. If he is having difficulty with a task, he may suddenly say “hug” and try to hug you. While I am sure he will adore you, please know that a hug during a difficult activity is an attempt to divert attention to escape the task. Therapists and teachers have turned that hug into a reward by saying “First [insert target behavior here], then hug.”

Evan may also get down from his chair or flop on the ground to escape difficult tasks. We often find that when he’s trying to escape, a visual schedule with breaks incorporated into that visual schedule will help keep him more on task even when academic concepts or therapy proves difficult for him.

Evan may also test you by eloping from you. As we’ve learned, that behavior is usually for the thrill of the chase. We’ve been following the rule that as long as he’s safe, we don’t chase him. He usually gives up and comes back when he figures out that no one will chase him.

Our philosophy is that we presume competence, allowing Evan to attempt the tasks his peers are attempting. If he’s having trouble with the task, we demonstrate it or help him with it a few times and allow him extra time or allow him to try again, which often promotes success.

If a picture is worth a thousand words, a video is worth 10,000, and a live demonstration with a teacher, therapist or peer is worth a million. At home, presuming competence has led Evan to success at skills such as making his bed, helping with laundry, using a broom, spelling some simple words and sounding out simple words as we read.

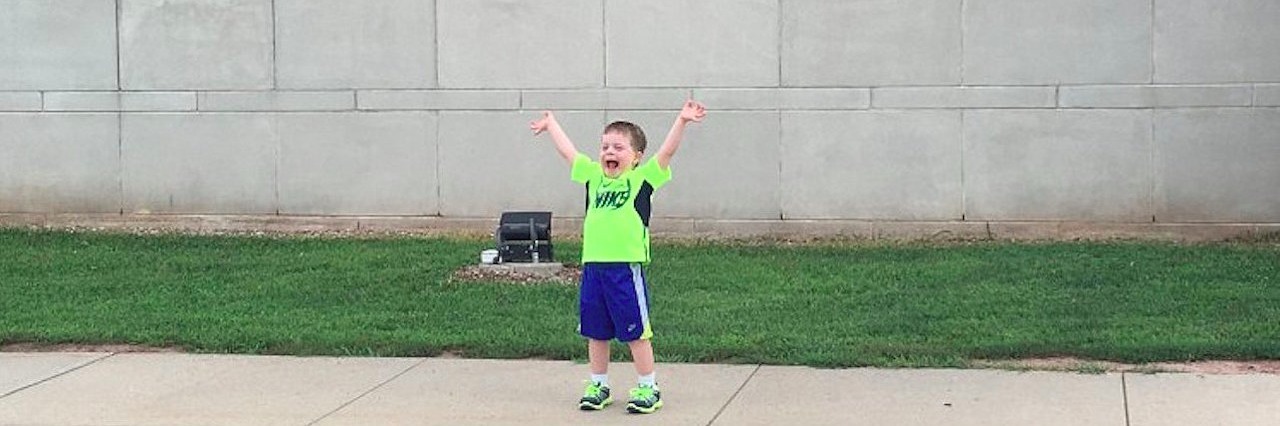

We’re also working on independence, but even we sometimes forget that. Evan will sometimes remind you that he doesn’t need you. This weekend, I shadowed him on the soccer field because he had been flopping on the field a lot during previous weeks. After a water break, I tried to return to the field with him. He said “Mommy, bye-bye. Sit down.” He wasn’t being rude. He was telling me in his own way that he no longer needed me on the field. He was right as he performed appropriately for the rest of the game. I have learned to trust him when he tells me he no longer needs me.

Evan takes a longer time to process information, so sometimes he may need a few seconds to let information sink in or even repeated instructions. Short commands (but not overly short) work best. I often use commands like, “Evan, please put your backpack on the bench. Please take your pajamas to the laundry room, or please take your plate and cup to the sink.”

One of Evan’s biggest challenges is speech. He is determined to communicate, but he sometimes forgets to use his words, and he may sometimes grab or push if friends get too close. At home, we’re working on teaching him to say, “Too close. Move please,” but he doesn’t always remember to say that when friends are in his personal space. Additionally, his words aren’t always clear. If you can’t understand him, ask him to repeat or to show you. That sometimes helps.

The children in Evan’s class will likely notice he’s different, and that’s OK. They may stare and ask questions. We always welcome the curiosity. It means they’re interested.

Recently, a child at Evan’s daycare asked me, “Why does Evan talk funny?” I told him, “Evan has something called Down syndrome. That makes it a little bit harder for him to talk, but he’s trying very hard, and he loves to play, just like you.”

We support telling his classmates about Down syndrome because we’d like them to start understanding Down syndrome even if it’s very basic information at this point. While students may notice Evan’s differences, we also point out ways that he’s more like them than different. If a student notices that Evan runs differently, we talk about Down syndrome and say that his muscles aren’t as strong, but even though that’s different, the fun he has is the same.

We’re so looking forward to this school year, to your insights and to the academic and other skills we’ll all be supporting for Evan. We are sure that with this amazing team supporting him, he will have a successful year. If you have any questions, thoughts or suggestions, please know that you can email or call.

We’re all on this journey together.

Regards,

Julie Gerhart-Rothholz