Why I Haven't Begun to Grieve, Even 6 Years After My Father's Death

Six years ago, on May 12, 2011 at 6:52 a.m., I got a screaming call from my mum. “He’s gone,” she said, barely able to speak through her wails. “Get over here quick, he’s gone, he’s gone.”

I don’t remember much about the morning my father died, nor the days after. It’s all a blur, like a half-remembered nightmare that leaves you feeling sick and shaken but not quite sure why. Part of me is thankful for this lack of memory, though I’m sure it’s hiding buried trauma like shipwrecks beneath calm and shallow seas. What follows is just a few snippets of my memory of that one morning — the broken masts when the tide gets low enough.

Putting on my clothes and shoes, barely able to think.

Running out of the house to where my parents lived; watching for ambulances, praying I’d see one speed past on the way to the hospital. A mantra repeating in my head — please don’t be dead, please don’t be dead, please don’t be dead.

Seeing the ambulance outside the house, the door open, a paramedic outside.

My mum on the sofa, inconsolable. The sound of machinery beeping, trying to resuscitate him. My words to my mother, barely believing them myself: “He’ll come back to us. He’ll come back.”

“I’ll never forget my mum, now child-like, screaming, ‘He’s still warm, he’s not dead.’”

The grave face of the paramedic, saying there was nothing more they could do. My verbal abuse, demanding he get back in there and bring my dad back.

It was lung cancer — a four month battle exactly, right down to the date, though he could’ve been diagnosed much earlier had the doctors not disregarded the shadow on his x-ray. We’re still fighting that legal battle. He had been released from his umpteenth hospital admission three days before his death, supposedly well enough to go home. My strong, powerful, indestructible father went from being extremely fit for a man of his age to being a shell, wracked by hacking coughs and cancer. Even his voice changed.

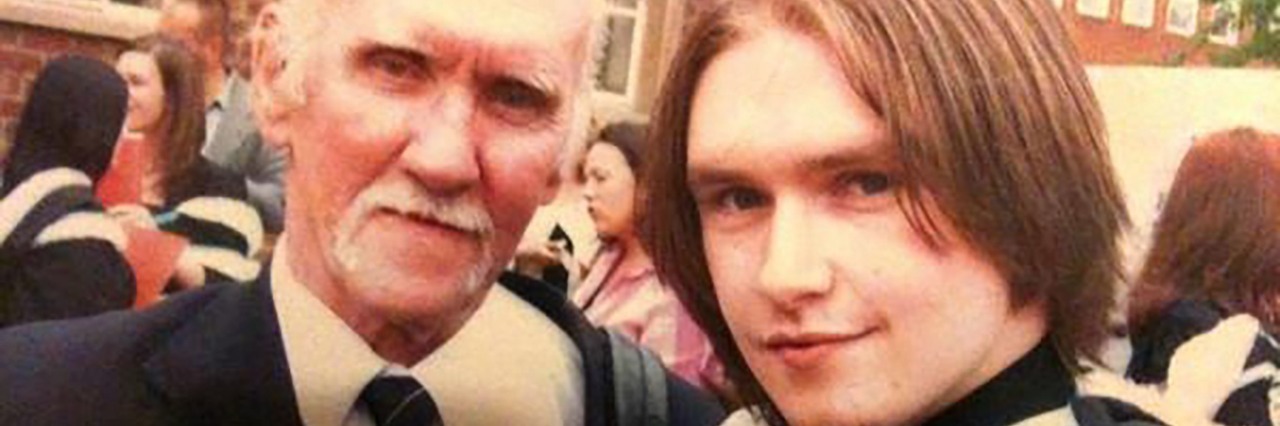

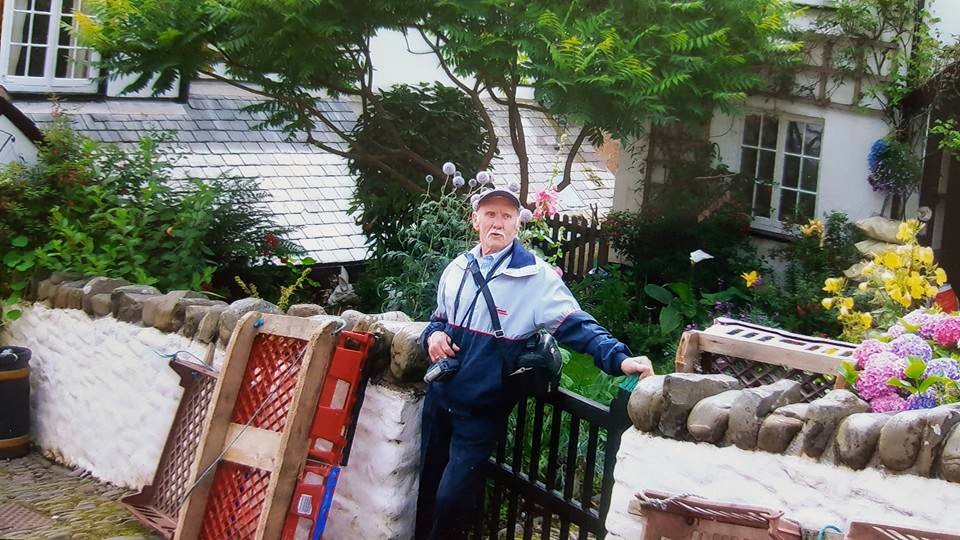

My father was always someone to look up to; everyone did. Born in 1933, he was a merchant sailor for much of his life. There wasn’t a nation on this earth that he didn’t see or sail to; he had a friend in every country, and that isn’t an exaggeration. Spend a few seconds with him, and that was all it took to like him immensely. He was friendly, welcoming, funny, charming and sweet. He accepted everybody and everything. He had his demons as so many of us do, but despite them, he loved life. He was, and remains, the man I aspire to be.

There’s a gap in my memory here; a blurriness I cannot see, no matter how hard I try and focus on it. I remember my half-sister came to the house, and we went into the room to see his body. I’ll never forget how he looked, nor how his skin felt. I’ll never forget my mum, now child-like, screaming, “He’s still warm, he’s not dead.”

He was.

I picked up his death certificate and downed three cans of Red Bull. For some reason, I wanted to tell the cashier I bought them from that my father had just died, but I didn’t. I saw memories of him wherever I turned; the chair he sat in, the shop he liked to go to. His inhaler sat on the table on which he’d left it just a few minutes before he died. My mum subsequently left it there for years.

The following days are even more of a blur. I made coffee for those who came to the house. I pushed my emotions, my grief, into the deepest darkest part of me and shut everything down. I simply existed; I had to. I stayed with my mum, and I remember an overwhelming fear that I would see him somehow, that his spirit would visit the house. I was religious then — one of the first things to go after his death — and the thought of seeing my father’s spirit terrified me.

I don’t know how I got through those few days apart from simply running from everything. My girlfriend at the time had to bathe me, I was so unresponsive. I visited him in the funeral home — spoke to him all the things I never said and wished I could. I crumbled into a child-like version of myself in that room, and I remember calling him “daddy” — a name I had not called nor thought of him as in 15 years. I remember the smell of that room — sickly, sweet, overwhelming. Occasionally, even six years later, I swear I can still smell it somewhere at the periphery of my awareness like a distant rumble of thunder, and when I do I’m immediately back there in that room, with the body of my father.

On the morning of his funeral — May 16th — my then-girlfriend had to dress me. “One step at a time,” she said. “Now we’re going to put on your shirt. Now we’re going to put on your tie. That’s all we’re doing — putting on a tie.” We had our problems, she and I, but I’m thankful for those few moments on those few days.

I wrote and read his eulogy to a small crowd in the church. I didn’t speak loudly enough into the microphone. I sang the hymns and cried through the words. I was a pallbearer outside the church, and carried his coffin on my shoulders, feeling his weight, shared among men I didn’t even recognize. I wonder what they must have thought of me. I wonder if they knew who I even was.

We buried him in a plot he’d picked out for himself long before he was even sick — a perhaps morbid trait of my parents and the older generation in general. There’s a story of the time my parents saw their shared plot for the first time, which encompasses everything my dad was. They were looking for the spot when my mum turned around and couldn’t see my dad anywhere. She’d found the plot, and wanted to tell him.

“Gordon?” she said.

“Over here, love.”

She spotted him lying nearby, flat on the ground, his arms crossed on his chest.

“What are you doing?” she asked.

“Testing out my grave!”

“Gordon, you’re on the wrong one!” she shouted. “Ours is over here!”

He was a man without a fear of death, nor a fear of life. The only thing he feared was losing his family; the only time I remember seeing him cry was when I told him I was moving out of the family home. I don’t believe a lack of crying shows strength, but I certainly believe a lack of fear does in his case, particularly surrounding death.

It’s a fear I don’t share. I haven’t grieved for my father’s death, even six years later, and don’t believe I’ve even begun to. My long-standing depression and anxiety deepened that morning, and I sank into a version of myself I don’t recognize. I’m still awaiting official diagnosis, but the preliminary one of depression with anxious/avoidant personality disorder (AVPD) explains a lot.

I fear death so much now that I cannot read nor hear about it. I can’t visit the house he died in. I can barely visit his grave. I spend my days battling the depression and the anxiety and fighting away the grief — I can’t let it get close to me, not yet, because I’m afraid if I did then it would destroy me.

I lost my dad when I was almost 24. Losing a parent at any age is hard, but I wish we’d had longer together. I wish I could’ve said all the things I wanted to say. I wish I could be half the man he was, staring death in the face with a smile and a wink. I wish I could hear his laugh again, hear his many stories. I wish I could hug him without the silly macho fear I used to have that I couldn’t show him affection. What a fool I was.

I wish, more than anything, that he could still be here.

If you are to take anything away from this article, then let it be this — love deeply, and love completely. Let nothing hold you back. We never know when the ones we love might leave us.

My dad’s final words to me, the day before he died, were laced in disappointment. I was supposed to visit, but I didn’t feel like it. I promised I’d see him the next day. He said, “I’ll see you tomorrow, son.”

I saw him, but he didn’t see me.

Follow this story on the author’s Twitter.

We want to hear your story. Become a Mighty contributor here.

Images via contributor