What the People Who Say ‘Just Say No’ to Opioids Don’t Get About Chronic Pain

Sometimes the news isn’t as straightforward as it’s made to seem. Erin Migdol, The Mighty’s Chronic Illness Editor, explains what to keep in mind if you see this topic or similar stories in your newsfeed. This is The Mighty Takeaway.

If you listen to some politicians, the solution to the opioid epidemic is simple: “Just say no.”

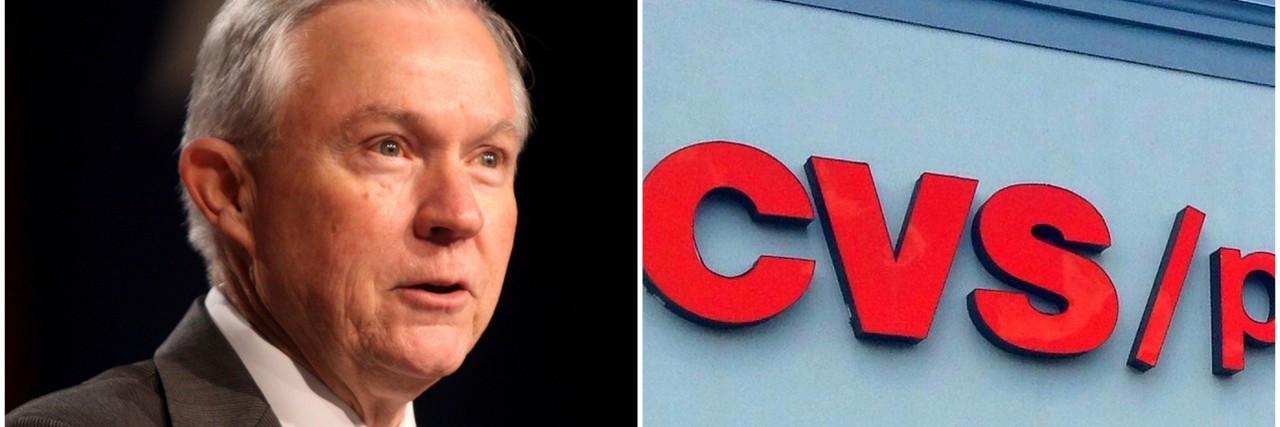

That was President Trump’s suggestion when he addressed reporters about opioids in August — “If they don’t start, they won’t have a problem,” he said. In early September, U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions said the same thing. “The best long-term solution is prevention. The best action is not to start. Just say no,” he said at an event in West Virginia. And last week, CVS Pharmacy announced it would begin limiting opioid prescriptions to a seven-day supply for certain conditions, suggesting that solving the opioid crisis begins with making it harder for patients to get opioid prescriptions in the first place.

To those with memories of D.A.R.E., the popular anti-drug campaign of the 1980s, this response might sound logical. But people who offer “just say no” as a solution don’t realize that for millions of people with chronic pain, opioids are the most accessible (and in some cases, only) pain relief that actually works — and studies show the majority never become addicted. Politicians who claim “just say no” is the solution to the opioid crisis (which has been proven to be an ineffective drug prevention strategy anyway) lump everyone who uses opioids together, as people who could get off them if only they put their minds to it. It completely ignores the toll chronic pain takes on a person’s life and the reasons they may have started taking opioids to begin with, while offering no solutions. If they “just say no,” what other options do politicians recommend?

At the most basic level, these “just say no” proponents need to recognize that the term “opioids” represents different types of substances used in distinct ways. Opioids are pain-relieving and mood-enhancing drugs, which range from prescription painkillers like codeine to illicit drugs such as heroin. Even though both are opioids, being prescribed codeine for chronic pain is not the same as using heroin illegally. This distinction, patients say, is what people fail to see when they talk about opioids.

For many people with serious chronic pain conditions like Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, fibromyalgia and rheumatoid arthritis, pain relief is a frustrating trial-and-error of treatment methods. Over-the-counter pills, non-opioid prescription medication, and alternative therapies like massage and acupuncture are effective for some but not all. Medical marijuana has shown promise, but it’s not legal in every state. Not all treatments are covered under every insurance plan, so some patients may discover their preferred method is impossible to afford even if it does work. Opioids are often among the least-expensive option; in fact, the New York Times reported recently that insurers are limiting access to pain medications with a lower risk of addiction or dependence while providing access to generic opioids, which are cheaper.

So when we talk about chronic pain patients who are using opioids, we’re talking about patients who are usually using opioids as a last resort. These patients take their pills as prescribed by their doctors and, for the most part, don’t become addicted to them — studies show only between 8 and 12 percent develop an addiction. Meanwhile, research indicates 75 percent of opioid misuse starts with people using medication that wasn’t prescribed for them. The majority of people who are being asked to “just say no” are chronic pain patients who are taking one of the only affordable, accessible, effective pain relievers they can get.

And even when opioids are prescribed by a doctor for a patient who truly needs them, they are already subject to restrictions designed to prevent addiction. Patients are often required to sign contracts stating things like that they won’t accept narcotic prescriptions from other doctors and won’t give the pills to anyone else. They also may be subjected to random drug tests. By telling people to take fewer opioids, you risk scaring physicians away from prescribing medications that are actually helpful, even to patients who are already following these stringent rules.

In reality, cliches like “just say no” only contribute to the stigma chronic pain patients already face for using opioids — while simultaneously ignoring the complexity of addiction. It makes it that much easier for emergency room doctors to deny opioids to those in agonizing pain, for pharmacists to give dirty looks to their customers filling opioid prescriptions, and for doctors to stop prescribing opioids out of fear, leaving responsible people in the dust. Even worse, people who say “just say no” rarely offer any alternatives to opioids. Trump, Sessions, and CVS haven’t released any viable plans. Just say no… and then what? Go home and wait for the pain to get better?

So, to the politicians and companies urging everyone to “just say no,” here’s what you can do to address opioid use without ignoring and alienating the millions of people who use opioids safely. Start helping the medical community fight the diseases that cause chronic pain, and find more pain relief options. We need more research into autoimmune disorders, connective tissue disorders, neurological pain conditions, cancer and any other currently incurable condition that causes chronic pain. We need alternative medications and treatments like medical marijuana, and insurance policies that allow patients to try every possible method and develop a regimen that works for them and is still affordable. We need to make sure doctors and patients have the ultimate power to decide what treatment option works best for them. And address the other factors that correlate more strongly to opioid addiction than being prescribed opioids by a doctor, like age, past traumatic experiences, and mental illness.

Most of all, remember that so many people using opioids are simply looking for a higher quality of life. While flippantly boiling the opioid crisis down to “just say no,” think of patients like Mighty contributor Sarah Hauer, who must deal with the consequences of society’s assumption that all opioids must be rejected.

“I don’t need to be saved from myself. I need to be saved from my lupus. A cure would eradicate much of this discussion. For me, lupus is controllable to some extent,” Hauer wrote on The Mighty. “So why is society hell-bent on taking away one of my necessary tools to control it? I need my opioid of choice, not to escape the world but to join it.”