Sometimes the news isn’t as straightforward as it’s made to seem. Sarah Schuster, The Mighty’s mental health editor, explains what to keep in mind if you see this topic or similar stories in your newsfeed. This is The Mighty Takeaway.

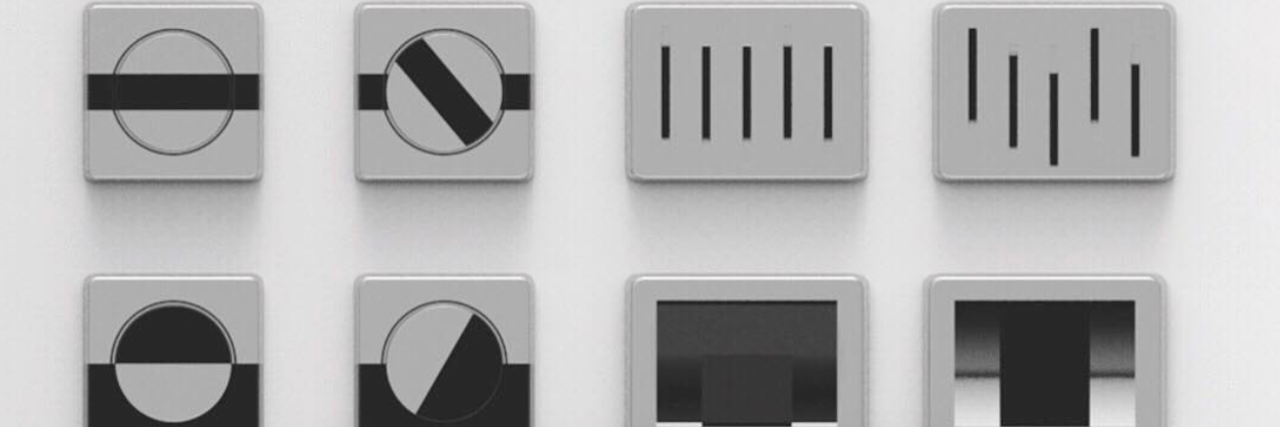

The design is actually pretty cool. It’s a light switch that uses humans’ natural preference for symmetry to remind us to turn off the lights. When the light is switched off, the design is “right,” complete. When turned on, though, the design is imperfect. The logic follows that we’ll be more likely to turn off the lights because we want to fix the design.

The only problem: It’s called an “OCD Switch.” I’m sure you can see where this is going…

A statement about the design reads:

Observations about human behaviour and the subconscious tells us that human beings are naturally attracted to order, pattern and symmetry; they feel uncomfortable when those are interrupted or when things seem off-balance… OCD SWITCH uses a simple design to manipulate and condition the user to associate saving electricity (turning off the lights) with something positive.

Great, nothing wrong with that. Humans like patterns and symmetry. This light switch might help save electricity.

But please, leave obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) out of it. “OCD is not an adjective” is a tired argument at this point, but when I see headlines like, “These Switches Use OCD to Save Electricity!” the issue goes beyond making light of a mental illness.

This isn’t about being offended or outraged, it’s about oversimplifying what it means to have OCD. As someone with multiple loved ones who struggle with OCD, it’s frustrating when others assume acting on compulsions is pleasurable, or that simply being able to straighten up everything in our world would “fix” OCD.

The reality of OCD is literally the opposite — the quick relief that may come from making something look “right” is short-lived. Understanding that means first understanding the difference between preference and obsession, impulse and compulsion.

Jeff Bell, author of the books “When in Doubt, Make Belief” and “Rewind, Replay, Repeat,” wrote one of my favorite blogs that explores just this, using his own personal experience living with OCD.

In his piece, called, “Pssst, OCD Is NOT an Adjective,” he shares two behaviors that both could be labeled “so OCD,” but explains why one (picking up sticks on the sidewalk) is actually part of his OCD, while the other (anally organizing his closet) is not. He wrote:

Those of us with OCD derive absolutely no pleasure or true benefit from our quirky behavior. In fact, our behavior gets in the way of our everyday functioning and leads to great distress when we can’t engage in it. This is key, especially in differentiating OCD-driven behaviors from non-OCD-driven behaviors that might look like OCD-driven behaviors.

Bell describes how he organizes his closet in a way one might describe as “OCD.” His clothes are sorted by type, his hangers are color-coded, the works. But the thing is, Bell actually likes rearranging his closet.

I can’t imagine being late for work because I’m stuck rearranging the hangers. (My quirky “ordering” does not get in the way of my day.) And, while I enjoy seeing my clothes hanging as if in some department store, I can’t ever recall feeling uneasy when they’re not.

He compares this to when he would spend hours of his time picking up debris from the sidewalk:

Contrast all this with my penchant for picking up rocks and twigs–an OCD compulsion during my worst years aimed at addressing the uncertainty posed by my doubt bully‘s nagging question What if one of those things kicks up into the spokes of a bicycle wheel and someone gets hurt? I hated having to pick up sidewalk debris, often watched by nearby pedestrians wondering what the heck I was doing. (I definitely derived no pleasure from this activity.) You can imagine how time-consuming this process could be.

What’s “so OCD” about his twig-picking compulsion is that it’s influenced by a nagging fear, also known as an obsession (in his case, that someone would get hurt), followed by a compulsion that appears to relieve the fear. The problem is, this isn’t a one-and-done deal. The cycle isn’t over when the debris is picked up, or when the “OCD Switch” is flipped. In fact, acting out these compulsions actually re-enforces the part of your brain that connects “fear of someone getting hurt” to “picking up X number of twigs, for X numbers of hours, or until it feels “right.’” This means next time the fear pops into your head, you’re more likely to act on your compulsion, more likely to keep doing it until it feels right, because you associate that action with the fear going away. And who wants to live with fear?

When this fear and these compulsions start taking up time, start causing you distress and start preventing you from living the life you want to live… that’s OCD. The irony of this all is that an “OCD Switch” would actually be unhelpful for someone with OCD. Fighting OCD means fighting something that isn’t perfect, and coping with it. It’s not turning off that light switch, and being OK with it. It’s learning to sit with the fear and realizing you can get through it. That you’re stronger than it. That we don’t have to make everything perfect in our lives.

Of course, OCD it’s a spectrum — not everyone with OCD has obvious compulsions. People with OCD can enjoy being organized (although many people with OCD are not), and people with OCD can even love the “OCD Switch.” OCD looks like a lot of things, and that’s exactly the point.

When OCD is associated with a preference for symmetry or when products advertise that making things “perfect” is what people with OCD want, we’re spreading misinformation about what the disorder really is. When I tell people someone I love struggles with OCD, I don’t want them to think of this light switch and assume they know what I’m talking about. I want them to ask questions. I want them to learn. I want to honor how hard it can be for people with OCD to resist their compulsions — not tell them it’s as easy as turning off a light.

Lead photo via yankodesign’s Instagram