The ABC TV series “The Good Doctor” has taken the world by storm. I have made a hobby out of reading the Facebook posts from all the fans. Everyone seems thrilled that an autistic person is portrayed in a setting like a hospital and operating room. I see endless posts from parents saying this show gives them hope for their autistic child. “I’m SO happy that TV land is finally portraying an individual with autism in a professional role. Freddie Highmore is doing a stellar job as The Good Doctor! I’d love to meet him someday!”

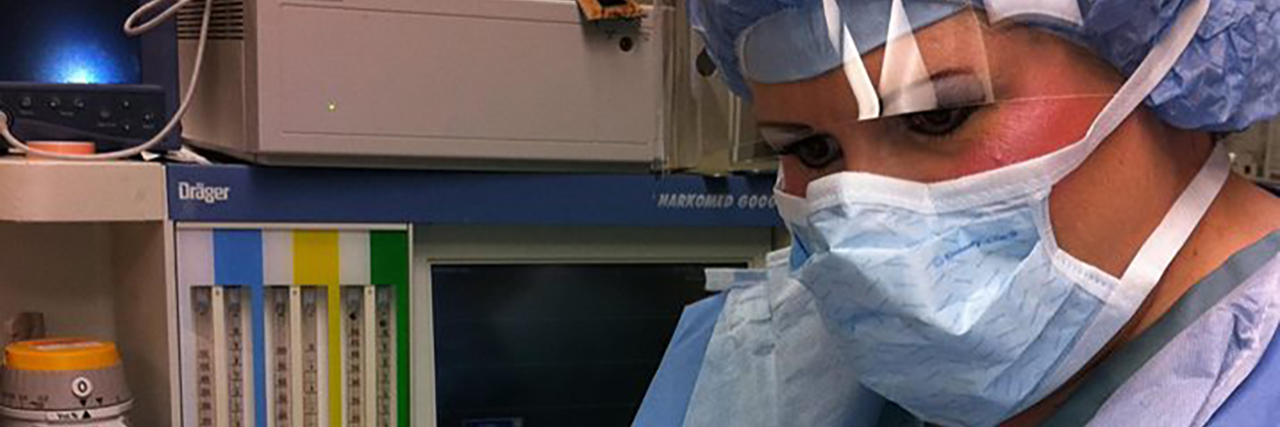

I’ve got some great news for everyone who watches this weekly show. There really is an autistic medical professional who works in the operating room, a Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetist who’s given anesthesia to over 50,000 patients for the past 30 years. This person has learned to work in the high-stress, fast-paced operating room, contending with not only surgeons, OR staff, patients and their families, but hospital rules and regulations and sudden changes of daily routines. This gets even better. This autistic individual didn’t even know they were autistic for the first 23 years of their career. That made life all the more difficult, not understanding why there were so many difficult social encounters. The whole environment also subjects one to massive sensory overload, causing extreme exhaustion by the end of each day. How do I know all this? Because I’m the Good Autistic Anesthetist!

How would you like to spend a day with me in the operating room? I get up at 3 a.m. each weekday morning. I’m out the door by 4:30 a.m. driving to work. I like that time to drive because there’s hardly any traffic, so not many headlights coming towards me to contend with. If it’s dark on my way home with lots of traffic, all those headlights cause major sensory overload and make driving extremely difficult. As I drive I enjoy peeking up at the moon and stars when I’m at a red light. It’s very peaceful.

After changing into scrubs and putting on a surgical hat, mask and visor, I’m walking into the operating room by 5:30 a.m., the room I’m assigned to for the day. Just like an airline pilot, I must go through a checklist to be sure all of my equipment is working properly, and I have all the supplies I need. In order to provide safe anesthesia, everything must be all in order and ready to go.

My great friend Temple Grandin has come up with many great quotes over the years. Unfortunately, one of them truly fits my work environment. It’s “Bad becoming normal.” In my work environment, this is a result of being short-staffed, hospital or national drug/supply shortages, and sometimes simply lazy staff. My coworkers also have to contend with these issues, but it is all compounded for me.

The operating room functions like the airline industry in that cases must start on time, just like the 6 a.m. flights must be rolling down the runway on time. If your first case of the day isn’t in the operating room before 6:30 a.m., it gets written up to administration, who investigates the cause of the delay. I never want my name to be that cause. To be sure I’m not the cause, I’ve got a lot to contend with to make it happen. This puts extreme stress on me.

First I check the anesthesia machine and go through the whole checklist function process. While that is going, I look over all the supplies and write a list of everything I need to stock. If everything I need was stocked by the anesthesia techs the evening before, I let out a sigh of relief. Otherwise I become the stock boy and have to get my supplies. This past week, here’s how it went. I opened the drug cart, which has to be opened by logging in your initials then scanning your fingerprint. This machine contains all the necessary drugs used for general anesthesia plus all other cardiac and emergency drugs for emergencies. It also contains Controlled Substances, meaning narcotics used for anesthesia. Upon opening, I found that the pharmacy techs hadn’t restocked the drawers during the night. Nothing. I didn’t even have the drug used to induce general anesthesia, and no antibiotics. My adrenaline started pumping.

Right then one of the OR supervisors walked into the room and saw my distress. “What’s wrong?” she inquired. “We need to get pharmacy up here right away to stock this cart,” I replied. “There’s nothing here to start the first case.” Grabbing her phone, she said “I’ll call them to get up here and stock.”

As I looked at other supplies, my list was rapidly growing. I needed 18 gauge needles, ten cc syringes, 60 cc syringes, 60 inch microbore tubing, oxygen masks, 7.5 endotracheal tubes, EKG patches, suction tubing, suction canister, Lactated Ringer’s liter bags, 100 cc bags normal saline, Sevoflurane liquid for the vaporizer, breathing circuits for the anesthesia machine, upper body Bair huggers, secondary IV sets, spinal trays, and spinal needles, a laryngoscope handle, and MAC 3 and 4 blades. I shot a glance at the clock and saw it was now 0540. Time was ticking away. I quickly grabbed a huge bin and headed down the hall to the supply room. This should be done by one of the anesthesia techs, but good luck on that happening, so off I went.

By the time I gathered all of those items from two supply rooms and got back into my operating room, it was 0552. Quickly putting everything in its place, I resumed the anesthesia machine check out. I then began assembling everything for the first case which was a bilateral total knee arthroplasty, or in lay terms, the patient was getting both of their knee joints replaced. The anesthesiologist was out in the pre-op area doing the nerve blocks on the patient’s legs. Once in the operating room, I would perform the spinal. These cases are typically done in this fashion, and once the spinal is placed I give a combination of drugs to induce a twilight sleep for the patient throughout the case. This is different from general anesthesia, where you render the patient into a drug-induced coma, place a breathing tube down into their trachea and place them on a ventilator throughout the case, maintaining anesthesia by a combination of inhalation anesthesia gas mixed with oxygen, muscle relaxants, narcotics, and other drugs like anti-nausea medications.

After assembling all the necessary syringes, I have to place the corresponding drug label on each one. The labels are color-coded and show the drug name on them. To be in compliance with JACHO, which is the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, I must write the drug concentration, the date, time and my initials on each syringe label. That’s tedious and time consuming. And the clock is ticking! I probably look at the clock 50 times throughout this whole process, from the time I enter the room until that first patient is being wheeled into the operating room.

Oh yes. I did forget one thing to add. As I’m doing all of this, about seven or eight operating room staff are in the room, all scurrying about getting all the surgical instruments in order, talking, and of course someone always blasts some heavy metal music. That adds to my massive sensory overload. The scrub tech is setting up endless trays of the joint replacement components and all the tools the surgeon will be using, including the bone saw which they test several times. That makes a spine-chilling, shrill sound. It’s controlled chaos. They are all talking, not only about the case but about everything that’s wrong at work, and complaining about everything. My brain has to process all of this, plus getting my own stuff ready. Does it sound overwhelming yet? Picture being autistic and coping with this every day.

Now the pharmacy tech has showed up to restock my drug machine, only she didn’t bring all the necessary items, plus she had a new employee that she was teaching how the machine operates. I had to step out of their way, again looking at the clock. It was 0605. In 10 minutes they would be bringing the patient to the room.

I used that time to quickly run over to the pre-op area to meet the patient, read over the anesthesia pre-op record, and discuss anything peculiar with the anesthesiologist. The nerve blocks had already been completed and everything was all in order. The patient had a history of high blood pressure, diabetes, sleep apnea. The sleep apnea would be an issue to deal with once I’d start sedating them because their airway would obstruct. That’s an issue common to anesthesia providers, ensuring a patent airway via various methods. Otherwise, a straightforward patient.

Rushing back to the operating room, my anxiety soared even higher. The pharmacy techs were still there at my drug machine, causing further delay. Finally, they left and I was able to check out all my necessary drugs and draw them up into the labeled syringes. Even if a case is not going to be a general anesthetic, you must still draw up all the drugs necessary just in case of an emergency situation in which you must rapidly induce general anesthesia.

Just as I was doing the last step, the nurse wheels the patient into the operating room. Glancing one last time at the clock, I let out an inner sigh of relief, as I’ve somehow made it in time. Now we get the patient onto the OR table, into a sitting position, and hook them up on all the monitors, the EKG, blood pressure cuff, oxygen sensor, and give them oxygen to breath with a mask. I give them some sedation, and as the nurse stands in front of the patient to hold them, I begin the sterile process of placing the spinal. I must first feel the patient’s spine for the landmarks I need. Then I don the sterile gloves and prep their back, numbing up the lumbar 4-5 level. I insert the spinal needle which goes between the vertebrae and into the subarachnoid space. I know I’m in the correct location when the clear cerebrospinal fluid drips out of the end of the spinal needle. I then slowly inject local anesthetic, aspirating on the syringe several times to see the swirl of spinal fluid, ensuring the tip of the needle remained in the correct place. Within a few moments the patient notices their lower body and legs are becoming warm, tingly, and soon they are completely numb from the waist down. We lay them flat, and all the preparations rapidly commence to prep them for surgery. Then the surgery gets underway.

Just prior to the actual surgery starting, we must all pause. The music momentarily gets turned down, and we must do what’s called the Time Out. This is where the circulating nurse holds up the patient’s consent, and the surgeon reads out loud the patients name, date of birth, ID number, and exact type and location of surgery. These checks have already been done multiple times by multiple staff, but the final check is done immediately prior to the surgeon making incision. The correct patient and correct surgery and surgical site must be verified. It’s a team effort.

Once the patient is flat, I continue doing my job, securing their arms on the padded arm boards, covering their upper body with a special warming blanket that blows warm air on them throughout the case to help keep their body temperature normal in the cold room, give more sedation, and hook up the continuous infusion of anesthesia I program the pump based on the patient’s body weight. I give the appropriate antibiotic via their IV. By this point the surgeon is handing me the sterile drapes to get clipped on the two IV poles which stand on either side of the operating table. That keeps the surgical side sterile. Then I sit down at the head of the bed and begin the endless charting and paperwork.

I must maintain extreme vigilance throughout the case, monitoring the blood pressure, heart rate and rhythm, oxygen saturation, carbon dioxide level, respiratory rate, maintaining a patent airway of the unconscious patient, and keeping track of blood loss and the progress of the surgery. There’s bright lights, loud music, multiple people talking, sounds from the monitors, phones ringing, text tones I must deal with while doing my job. At the conclusion of surgery, we transport the patient to the recovery room, get them hooked up on all the same kind of monitors, oxygen, and give report of the patient and surgery to the recovery room nurse. The patient is already awake by this point. I review all the paperwork to ensure every last item is complete. Then I hurry back to my operating room to get ready for the next case.

It is not unusual for me to go eight hours without getting to use the restroom, eat or drink anything. That’s life for a Nurse Anesthetist. Being autistic makes this whole picture extremely exhausting, both physically and mentally. By the end of the day every last ounce of energy has been drained out of me. So when I read the Facebook posts of how enthralled millions of people are with “The Good Doctor,” I want to wave my hands and holler out, “Over here! Over here! I’m autistic and doing all this!” I sort of feel like I’m stranded on a tiny deserted island waiting to be rescued. I’m not only an autism advocate, but a medical professional providing all anesthesia services to patients for the past 30 years.

— Anita Lesko, BSN, RN, MS, CRNA

We want to hear your story. Become a Mighty contributor here.

Photos provided by contributor.