Holden Kasky had one last thing to do before meeting his older brother, Cameron, to go home from school. It was February 14, and he still had a Valentine’s Day message to deliver.

But before the 16-year-old could give out his final card, the fire alarm went off.

“We thought it was a fire drill, but that was weird because we had a fire drill earlier,” Holden said. A freshman at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, he recalled being told to go outside and then back inside to take cover.

While the brothers darted back and forth, a former student had entered the school and started shooting. The Kaskys ran to Holden’s classroom and hid in the back along with Holden’s teacher and 20-or-so other students — teens, who, like Holden, are on the autism spectrum.

“My heart was pounding, that’s how scared I was,” Holden told The Mighty. “We had to hide and duck in the classroom. There were so many students crowded because we had all the lights off.”

Finally, after hours of students crouching in darkness, the police broke down the classroom door. “I heard loud smashing,” Holden recalled. “The door was broken, and all the glass was shattered everywhere.”

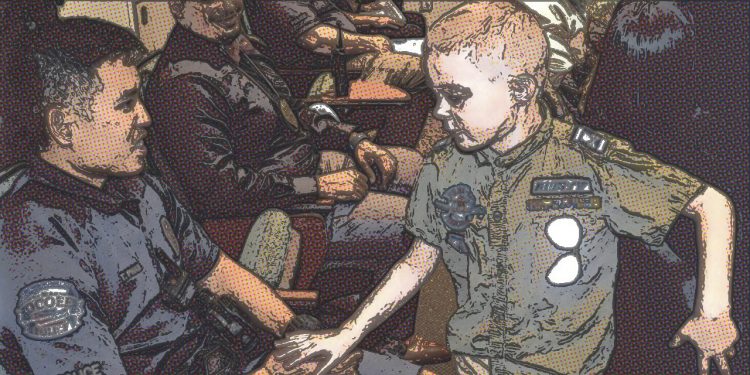

Holden and his peers were told to raise their hands behind their heads and evacuate the room. Cameron told police the room was filled with students with disabilities — that not everyone could raise their hands. “Some of the kids can’t really speak,” Holden explained. “They said, ‘Run with your hands up.’” Holden dropped his backpack and ran out of the building with his brother.

The Parkland shooting lasted only six minutes. Seventeen people lost their lives and another 16 were injured. It took four hours from when the shooting started for Holden and Cameron to be reunited with their father, Jeff, who picked them up at a hotel several miles from campus.

Before the Parkland shooting, Holden had practiced a variety of fire, tornado and active shooter drills. While he’d actively participated in drills, he never thought he would need them. “That’s what gets you,” Holden said. “Until it comes, you’re just like, ‘Bleh, I don’t really like this. Can we go back to class?’”

Emergency preparedness is often an integral part of a school’s curriculum. Across the U.S., students simulate what they would do were there a fire, natural disaster or, since the Columbine shooting in 1999, an active shooter.

But not all schools require active shooter drills despite more than 100 school shootings in the U.S. since the Sandy Hook shooting in Newtown, Connecticut, on December 14, 2012.

Without a federal mandate, it’s up to states to determine what — if anything — schools practice. While some states issue guidance or require a certain number of drills to be performed each year, what schools do during an emergency is left to districts and individual schools to decide — and modifications for students with disabilities are rarely included.

An investigation by The Mighty found that guidance given to schools forces students with disabilities, teachers and parents to dictate what needs to happen amidst a crisis.

With minimal training, inaccessible recommendations and guidelines that offer little beyond “considering disability,” students, parents and teachers are left few resources to navigate these life-or-death scenarios. It is often their responsibility to make sure the person with a disability is included in the school’s plan — a burden required of no other student demographic.

“The standard recommendation now is more or less ‘run, hide, fight,’” said Irwin Redlener, M.D., director of the National Center for Disaster Preparedness at Columbia University. “Depending on the person with a disability, it may be very difficult to do any of those steps, and under those circumstances, the school, in advance, needs to think about the needs of people in the school.”

The Mighty reached out to every state office responsible for emergency preparedness at schools across the country to understand how drills are handled at the state and local level. Twenty-nine states responded to our initial request, and 16 responded to questions about emergency preparedness for people with disabilities, though other states had general information about guidelines for people with disabilities on their websites. Eleven states said plans should include all students, including those with a disability. Three — Arkansas, Oregon and South Dakota — said they did not have any disability language in their policies.

“It is long past time that we act to prevent senseless acts of gun violence, and implementing active shooter trainings and emergency preparedness in schools and in all workplaces are critical to those efforts,” Sen. Maggie Hassan (D-NH), who parents a child with cerebral palsy, told The Mighty. “All students deserve the opportunity to learn and grow in a safe environment — regardless of personal circumstance, and it is vital that any active shooter trainings or emergency preparedness plans have specific plans in place to support individuals who experience disabilities and may require additional supports in an emergency.”

In Florida, where Holden and Cameron live, each school district is tasked with creating its own emergency preparedness plan. The districts work with local law enforcement and emergency preparedness offices to develop plans for students and staff. The state offers a school safety self-assessment, which asks schools to ensure their emergency checklist includes ways to evacuate people with disabilities.

The most common guidance provided by states comes from the Readiness and Emergency Management for Schools Technical Assistance Center (REMS) — run by Synergy Enterprises, Inc., a private management consulting firm contracted by the U.S. Department of Education.

In 2013, REMS, in partnership with the FBI, FEMA, Homeland Security and several other government offices, created a federal outline for school emergency management planning.

There are three basic options REMS gives for an active shooter scenario: run, hide or fight:

You can run away from the shooter, seek a secure place where you can hide and/or deny the shooter access, or incapacitate the shooter to survive and protect others from harm.

Part of putting together a plan, according to REMS, includes creating a “core planning team.” Team members should include support staff, first responders, school administrators, teachers, students, parents and those with disabilities.

Having a crisis planning team is also recommended by the National Association of School Psychologists and the National Association of School Resource Officers. Like REMS, NASP and NASRO’s “best practice considerations” for active shooter scenarios is referenced in guidance issued by several states. Both groups recommend schools “consider including a disability specialist as a member of the team.” The document does not require these disability specialists be people with disabilities. Instead, it offers school psychologists as potential team members who can provide both mental health and disability guidance.

While having a person with a disability on these teams could result in safer protocols for disabled students and staff, people with disabilities are rarely included in these discussions. In 2012, the Missouri School Boards’ Association discovered that many schools in the state did not include “special services representatives” and nurses on their planning teams — nor did the plans consider the disabilities and medical conditions of students and staff when creating, reviewing and practicing emergency response plans. Later that year, the state created a task force to address emergency preparedness for students and staff with disabilities.

A lack of consideration when it comes to disability is not unique to Missouri. The Mighty spoke to dozens of students and teachers with disabilities who said they were not included in the development of plans nor were their mobility or health-related concerns addressed by administrators without the disabled person’s prompting.

REMS states that plans should comply with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and integrate the needs of people with disabilities as well as those who may require medication, personal assistance services or experience severe anxiety during traumatic events. Aside from advising schools “to be aware of disability-related accessibility concerns,” REMS provides few concrete recommendations for schools to follow. REMS recommends visualizing potential escape routes including physically accessible routes for students and staff with disabilities. However, it advises against elevators and offers no suggestions for students and staff who have mobility concerns. The most specific recommendations offered are to have visual signals and alarms for relaying information to those who may be deaf or hard of hearing, as well as communicating with emergency responders so they know where people with disabilities are sheltering.

No other disability-specific recommendations are given within the 75-page document.

Michelle Gay spent all of December 14, 2012 waiting for her daughter, Josephine, in the parking lot of Sandy Hook Elementary School. The first-grader had turned 7 three days earlier, before a gunman entered her classroom and killed her and 20 other children.

“Sitting in the parking lot that day, the whole day, it took a very long time before we were told what had actually happened,” Gay said. “It was this very strange out-of-body kind of experience, just observing and watching. And because I had been a teacher, I was observing a lot of things I knew weren’t supposed to happen — things that were not a part of the plan.”

Josephine — or “Joey” as family and friends called her — was “a bit of a rockstar” within the Sandy Hook community. She was on the autism spectrum and had apraxia. Despite being “nonverbal,” she was known to contribute her voice. In her mainstream class, her classmates learned sign language and used her iPad to communicate with her.

She was “love, light and affection,” Gay said.

No one was prepared for what happened that day.

“We had procedures and practices in place, and to be honest with you — they weren’t very considerate of my daughter at all,” Gay said. “To require an autistic child to be hiding in silence for an extended period of time, that is not a very realistic expectation.”

Beyond the standard guidelines put in place for the rest of the students at Sandy Hook Elementary, Josephine’s safety was dependent on her aide, Rachel D’Avino, who gave her life trying to protect the first-grader. Another autistic student, Dylan Hockley, 6, also lost his life that day. His special education teacher, Anne Marie Murphy, died protecting him.

“It’s amazing to me how we just take it for granted that our special ed staff is just available to figure it out,” Gay said. “We get sort of a false sense of security, as parents, as educators as well, when we say, ‘Oh, we don’t have to worry about Josephine because she’s got her own one-on-one.’ But when we think like that we really fail to do the planning and have the conversations about what are all the things that could happen during the day.”

After Sandy Hook, Gay knew she had to act. “I just remember thinking, ‘Wow, I have to do something with this,” she said. “I have to share this with other people.”

Gay partnered with fellow Sandy Hook mom Alissa Parker, who lost her daughter Emilie, to create Safe and Sound Schools — a nonprofit that offers free resources designed to promote school safety.

“There’s not a lot in place out there for families with children who have any kind of disability, any kind of anxiety, any kind of health condition or disorder,” Gay said. Instead of promoting “run, hide, fight,” Safe and Sound Schools encourages teachers and administrators to assess, act and audit.

Gay told The Mighty:

A lot of these active shooter protocols or these protocols for violent situations — in protecting our students, “typical” or otherwise, from these situations — they are based on federal guidelines such as “run, hide, fight.” When you look at a lot of our disabled population, very few of those options are realistic. My daughter could be assisted, perhaps, in the hiding part. But she wasn’t able to run and she certainly wouldn’t be able to fight, nor would her typical peers have been able to. Just like we do with all levels, all developmental levels, all ability levels, we have to look at “OK, who do I have in any given circumstance or moment in the day with me and what do I need to do to support that child in these circumstances?” So it is highly, highly individualized.

The organization’s “Developmental Levels of Safety Awareness” explains what students can be expected to do, based on their developmental level, in an emergency. “When we think about how we want to teach and train, let’s think about what is manageable and psychologically safe and truly empowering and not overwhelming for the students in front of us,” Gay said.

“Stay Safe Choices” is for when it’s time to “act.” The guide includes images modeled after task cards that can help children understand what they need to do, as well as “play parallels” that allow students to practice emergency skills in everyday scenarios. For example, teachers can have students play hide and go seek in the classroom instead of telling them to hide because a “bad man” is in the building. Rather than telling children or those with developmental disabilities to fight or counter, guidance is broken down into “get out, keep danger out or hide out.”

“We teach those very basic things. We talk about all the different ways we would get out of an area that’s unsafe,” Gay said. “We literally walk through it, we literally roll through it — whatever we have to do. But we create that muscle memory.”

To make sure schools consider students of all abilities, Safe and Sound Schools offers its educational material for free on its website. “This exists as kind of a place to start and a model,” Gay said. “But we know the very best special educators, very best educators and parents of special needs children will take that idea and say, ‘Oh, if I adapt it this way it will be perfect for my child.’”

In addition to teaching emergency preparedness skills to students in a developmentally appropriate way, Safe and Sound Schools offers educational materials for teachers and administrators on a variety of topics including making schools structurally safer to launching community and statewide initiatives.

“We shouldn’t be surprised when it comes to safety,” Gay said. “We should talk about all of these things ahead of time. We should plan for a variety of circumstances and make sure the staff member feels safe in their responsibilities for the child and feels like they have all the tools necessary — the experience and the practice necessary — to keep that child safe in any set of circumstances.”

Lisa Crane was working as an elementary school principal in Texas when the Columbine shooting happened. Fearful for the safety of her students, Crane knew something had to be put in place to protect them. At the time, active shooter plans for schools did not exist, so Crane turned to her husband, Greg, a former law enforcement officer, for help. The plan Greg devised was adopted by Crane’s school and became the backbone of ALICE Training.

Today, ALICE Training Institute bills itself as the “number one active shooter civilian response training for all organizations” and claims to have trained more than one million individuals across all 50 states, as well as 4,200 primary and secondary school districts. Its program offers a longer variant of run, hide, fight — alert, lockdown, inform, counter and evacuate.

“The federal government, which typically outlines what needs to be covered, does not have anything in there for safety protocols for that [disabled] child,” Crane said. “But just because it’s not in the paperwork doesn’t mean it can’t be brought up.”

ALICE training includes language regarding students with disabilities. It’s something Crane, who has a background in special education, worked with her husband to include.

“We have recommendations for special ed,” Crane told The Mighty. “Upon request, we do put it in our training as kind of just a one slide. Now we don’t go into a lot of detail because the mere fact that it is about special needs.”

The guidelines, she added, are open-ended because different disabilities require different accommodations. “It’s mostly saying, ‘Don’t forget about them; hey, you have options,’” Crane said.

In listing these options, ALICE has one page of text dedicated to its “special needs” considerations. Crane said a child with a learning disability could be expected to follow the protocols other children in a mainstream class follow. The recommendations would be different for students with multiple disabilities.

Crane noted it’s up to the parents to make sure safety protocols are discussed in parent-teacher meetings, written down and communicated with the school and district if the student needs to have those protocols modified.

ALICE advocates for effective barricades that would allow students in self-contained classrooms to shelter in place. For students who are mainstreamed but cannot evacuate, ALICE recommends staff stay behind with the disabled student and barricade the room.

Through their training program, the Cranes have worked with schools for students who are deaf as well as students who are blind. Learnings from these schools have helped ALICE include visual alerts and electronic messaging as part of its recommendations. ALICE has social stories provided by schools and other educators, used to explain emergency protocols to students on the autism spectrum. It’s also provided security protocols for sheltered workshops and centers that care for adults with intellectual disabilities — working with parents and caretakers to devise plans. No adults with disabilities have been consulted in the making of any of its protocols.

To receive ALICE training, school districts must hire ALICE to work with their schools. ALICE provides “e-learning” to teachers, which includes a basic training program and then an add-on for teachers who have students with disabilities. It’s up to the district to decide which teachers, support staff and administrators are required to take the additional training.

Katelyn Shelley, an occupational therapist who works with elementary and middle school students on the autism spectrum in Michigan, went through ALICE training but said her school did not require any disability-related modules.

“We’ve never talked really about kids with disabilities and special needs,” Shelley told The Mighty. “We’ve had the general ALICE training, like a muted down version of that because when I went to take it they ran out of space for all of the staff to go through the mock situation and everything, so I just got a talk and a presentation.”

When questions were raised regarding what to do for students with disabilities, Shelley said teachers were told to “just do [their] best.”

“That’s not really a helpful suggestion because we’re all doing our best, but we need to have a plan,” she said.

Shelley did not receive ALICE’s training document for students with disabilities, nor did she know any special education-related training existed. She also noted it would be difficult for teachers of students with disabilities to address the needs of their students while following protocol:

When part of the ALICE protocol is to barricade your classroom, and you think to set up your classroom, you know, putting tables in front of, blocking the door, shutting off the lights, all of these things require physical people to do that. And when you have classrooms who are self-contained students, which are already kind of short-staffed and don’t have enough to manage the general day-to-day behavior of the classroom, I don’t see how there is going to be enough physical bodies in the room to do all of those things and keep the kids safe at that moment.

During one drill, Shelley and a student left the school’s therapy room not realizing the school was practicing a lockdown. The room they were in didn’t have a PA system, and it wasn’t until they were in the hallway that Shelley realized the school was in the middle of a drill.

Students within the elementary school’s self-contained autism classroom did not participate in this drill.

“It just wasn’t worth going through the drill when we know we’d have students who would act out significantly,” Shelley said.

Without concrete recommendations for students with disabilities, it becomes the job of students, teachers and parents to make sure the school has an accessible evacuation plan.

The Mighty surveyed 347 parents, teachers and students and found that 55 percent of parents whose kids have disabilities said they feel their school’s protocols were enough to keep their children safe. But when asked the same question, only 21 percent of students with disabilities felt schools were doing enough, compared to 31 percent of teachers.

After hearing news of the Sandy Hook shooting over her car radio, Laura Clarke, Ed.D., a special education teacher, pulled into a parking lot in Kentucky to call her colleague, Dusty Columbia Embury, Ed.D. In addition to being special educators, both Clarke and Columbia Embury parent children with disabilities.

”Our children would be dead at this moment,” Clarke told Columbia Embury on the phone. “There’s no way that there’s a plan in place at their schools that would keep them alive through this situation. We’ve never trained or practiced for any of the things that they’re describing teachers had to do in order to keep kids alive.”

Realizing they were unprepared, Clarke and Columbia Embury — who now teach future special education teachers at Eastern Kentucky University — developed a way to ensure students with disabilities are considered.

The two educators created a guide for special education teachers, which they published in “Teaching Exceptional Children,” a peer-reviewed journal for special educators. In it, Clarke and Columbia Embury advocate for adding emergency preparedness protocols to students’ individualized education plans or 504s. IEPs and 504s are legally-binding documents detailing the supports students with disabilities need to be successful.

These customized emergency protocols would be added to an IEP, like behavioral intervention plans are, as supplemental materials. Columbia Embury and Clarke refer to their emergency preparedness document as an “individual emergency and lockdown plan,” or IELP.

“This is a newer conversation that we’re all just now starting to have,” Clarke said. “It should be part of what schools are doing to provide support for kids because that’s our ultimate goal, to make sure our kids come to school safe and they leave school safe. If they’re not prepared for a crisis, then we can’t ensure we’re doing our best to help all of our kids.”

Parents, teachers and students can work together to draft an IELP that makes sense for that student based on the school’s emergency protocols and the student’s needs. During the IEP meeting, students, parents and teachers should discuss the school’s plan as well as the layout of the building. Accessibility issues, as well as any challenges the student may face related to their disability, should be addressed, and alternate plans devised. Teachers should also make sure students have what they would need during a crisis with them at all times — whether that’s critical medications or a familiar object the student can use to self-soothe.

“It’s really not starting from scratch,” Clarke told The Mighty. “It’s taking what we already know about the child, and it’s taking the strategies we already know work to help students learn and grow and putting those in place under the lens of if there’s a lockdown.”

Though adding emergency preparedness measures to a child’s IEP could help students with disabilities in worst-case scenarios, the majority of parents The Mighty spoke to were unaware that planning for emergencies within these documents was an option. Out of 118 children with IEPs, less than 24 percent had individualized emergency protocols documented.

“Just like the IEP, writing a document isn’t magic, and it doesn’t solve the problem,” Columbia Embury said. “It just gives us the recipe for getting to our goal. So once we write it, that doesn’t actually solve the problem. Now we have to find ways to implement it, so we do have to teach the skills, monitor their learning and progress and give them opportunities to practice.”

Whereas neurotypical and able-bodied students may only need to practice lockdown drills once or twice per year, students with disabilities may need more drills to be prepared. It’s not enough to just practice in one classroom, Columbia Embury said. What if the student is at lunch or in the gym during a crisis? Students, as well as their teachers, should be prepared no matter where they are located.

Teaching these skills, Columbia Embry added, would be like teaching any other life skill:

We teach social skills to students with disabilities. We don’t only teach it in the speech classroom. They might start there to get the basics down, and then they would do it in a classroom and then they do it in the lunchroom and then they do it in the hallway, and then they do it in a small peer group and then they do it in a large peer group. It’s a controlled process, and it’s a supportive process, and it’s scaffolded based on the student’s needs.

It’s not just Columbia Embry and Clarke advocating for emergency preparedness inclusion in IEPs and 504s. Both Michelle Gay of Safe and Sound Schools and Lisa Crane of ALICE Training Institute told The Mighty that parents should demand emergency preparedness is included in their child’s IEP.

“We are encouraging all of our schools, our parents, to really look at the IEP and 504 as their strongest tool right away to ensure that any type of safety instruction or education or drill or practice is being considered in a very individualized way for these particular kids,” Gay said.

IEP meetings need to include more than just the student’s primary teacher. Aides should be involved too, Gay said, adding:

Very often the aides aren’t present at the IEP meetings with the family. Nobody knows that child in the building probably better than that one-on-one aide, but we’re not asking them, and they have a lot to say. A lot of them are very fearful. They love the children they take care of and work with all day, and they want to know that if the worst happens, they’ve got a plan — and not just one but two or three they can fall back on.

Aides and paraprofessionals should also take part in drills. In one school district in Ohio, none of the aides who work with disabled students participate in drills, a teacher employed by the district told The Mighty. The district won’t pay them to be there on service days.

At a school where all of the students have disabilities, what disabled students do in the case of an emergency isn’t an afterthought — it’s the first thought. To make sure its students are as safe as possible, Lavelle School for the Blind in the Bronx practices drills with all of its students — there is no opting out.

Many of Lavelle’s safety measures are structural. The school, which takes up an entire city block, is fenced in. The parking lot is automated and requires a key for staff to park. Visitors must “buzz-in” to enter the school and then wait in a separate reception area until an escort arrives to take them to their destination. Staff members are required to sign in and out through a digital system that requires their fingerprint and the last four digits of their social security number anytime they enter or leave the building. During dismissal, staff and security guards escort students to their busses.

The school also uses security cameras at each entrance and within the building itself. Outside, there are strobe lights to alert staffers the school is on lockdown. Each classroom has its own “night lock,” a small metal device teachers can slide under their classroom door, making it impossible for an intruder to enter.

The rest of Lavelle’s protocols are similar to what able-bodied students at a mainstream school would be asked to do but with adaptations to help students who are visually impaired, hard of hearing or have other disabilities. As part of lockdown drills, students hide out of view from the door. If they need to leave the classroom, orientation and mobility instructors are available to help students exit the building as safely as possible. For students who use mobility aids, staff members are assigned to carry students down the stairs once the elevators are turned off.

Most importantly, Lavelle’s staff knows how to work with the students who attend their school. If there is time for a blind student to grab their cane, that need is accommodated. “We would know never to pull a student without telling them where they’re going,” said Diane Tucker, Lavelle’s upper school principal. “They have to grab the staff member’s elbow so the person is actually guiding the student.”

For students who are anxious or have trouble breaking routine, Tucker recommends letting them hold on to a comfort item for an added sense of security. “Our staff is really good at knowing which students need more help and just trying to comfort them and be with them and support them as they get down to a safer area,” Tucker said. “We really have it down to a pretty good science at this point.”

As much as Lavelle tries to anticipate and prepare for every kind of crisis, successful emergency preparedness for students with disabilities is more than just practicing lockdown drills — it’s making sure first responders are prepared as well.

That’s where Tom Hanney, a retired New York City police officer and detective, comes in. Hanney created and now oversees the school’s security protocols and has established a relationship between the school and New York City’s 47th police precinct. “I have very good rapport with 47th precinct, which covers our school,” Hanney told The Mighty. “I’m in direct contact with their community policing unit and community affairs unit. They have copies of all our plans, our floor plans, our evacuation procedures.”

Most first responders, however, are not trained how to respond to emergencies involving people with disabilities. A former police officer and parent of a child on the autism spectrum, Stephanie Cooper started Autism Law Enforcement Response Training (ALERT) to train law enforcement and first responders how to interact with people on the autism spectrum and other disabilities in an emergency situation.

“There are very few training programs out there for law enforcement and first responders in regards to how to interact with individuals that have disabilities,” Cooper said.

Cooper told The Mighty her son has never trained for an active shooter situation at school and that it would be difficult to prepare him. “I believe in an actual emergency situation that he would shut down, have a meltdown and not remember what to do,” she said. “My son has [shown] no sense of danger awareness. He would possibly even run towards the shooter.”

Because children on the autism spectrum may react differently to emergencies, it’s up to first responders to be able to identify students with different communication needs.

“Officers and first responders need to know the limitations of the special needs children at the school,” Cooper explained. “Officers and first responders need to formulate a plan with the school by utilizing the school resource officers and teachers during an emergency situation.”

It’s the school’s responsibility, Cooper added, to let local law enforcement agencies know the needs of its students, as well as which classrooms and buildings students with disabilities are in. It shouldn’t take an emergency or a school shooting for officers to be acquainted with disabled students in the communities they serve, Cooper said, adding:

Officers can also do hands-on practice drills with special needs children at their local school. This gives officers that hands-on experience working with children with special needs during an emergency situation practice drill, as well as it [gets] the children with special needs used to seeing what an officer would wear to an emergency situation and working with those officers and how they would react to an emergency situation.

During the Parkland shooting, Jeff Kasky was concerned for his sons’ safety, not only in the presence of an active shooter, but as first responders made their way to Marjory Stoneman Douglas. “I hope that when the police get to the room they’re both in, I hope those cops understand that it’s a special needs room and to have the appropriate expectations,” Jeff recalled thinking at the time.

Fortunately, the Coral Springs police were prepared, thanks in part to a training session Jeff helped facilitate in partnership with the Autism Society of America’s Safe and Sound program.

“Coincidentally I guess, I was part of the team that presented that program down here in South Florida to maybe a dozen law enforcement agencies just about a year-and-a-half ago,” Jeff told The Mighty.

The program prepares first responders, including police officers, for how to interact with people with developmental disabilities during times of crisis. “So when they show up on a scene, they know that they may stick up their gun in someone’s face and say, ‘Let me see your hands, let me see your hands’ but that person may not necessarily comply,” Jeff said. “If they don’t have the training, then it could be disastrous.”

In addition to its one-day training program, the Autism Society offers resources to parents and first responders on its website. ALERT also offers free autism training and autism sensory kits to first responders nationwide. However, with thousands of schools and law enforcement officials across the country, these resources don’t do much unless they are utilized.

“My advice is: call your school, call your police department, call your fire department, call your paramedics, call your first responders,” Jeff said. “Make sure they have some kind of training that teaches them how to recognize when somebody has a developmental disability and how those people may respond to their commands.”

Zoie Sheets, a graduate student with fibromyalgia in Chicago, isn’t confident her school or first responders would help her in the case of an emergency — and for good reason. When Sheets, now 23, was an undergrad at the same university, her school neglected her needs during both a drill and an actual fire.

Sheets, who asked that the name of her university be kept anonymous, was told at the beginning of the semester to email two separate addresses regarding her disability (she uses a cane) and where she lives, so during an emergency, she could be evacuated safely.

Sheets complied, but her school did not, she said:

The entire drill came, ended, and they moved on without having ever done anything. I contacted the head of campus housing — not the head of my building, the head of all of it — and told her what had happened. And she said, “Oh yeah, on drills we don’t usually concern ourselves with practicing those things, we just want to make sure we practice like getting the doors open, getting people out quickly, making sure people know where to gather, etc.”

And I instantly pushed back and said, “OK, but if you’ve never practiced rescuing me, what the hell happens as soon as there’s a real fire?” And that never really got resolved. I never really got a sufficient answer. I got a, “Yeah, maybe you’re right.”

The same thing happened during an actual fire in her residential building. After an alarm in the building went off at 2 a.m., Sheets and a friend waited for first responders to help Sheets evacuate. But first responders never came, forcing Sheet’s friend to help her get down the stairs. At this point, Sheets spoke with the police chief but said his response was dismissive:

It was very, “Oh, well, we didn’t know there was a disabled person in this building.” And I pushed back and said, “Well, I am registered, I did every step that you told me to to make sure that you knew. And if those lists aren’t getting checked, I’m getting pretty concerned because I’m a cane user. But there’s also a wheelchair user and a walker user in this building and having their friends get them out may prove more challenging because their mobility is more limited than mine.”

Given these experiences, and one other fire in an academic building, Sheets is fearful of what would happen during an active shooter situation.

“It angers me to look back and reflect on just how typical that felt to me,” Sheets said, regarding her school’s lack of preparedness. “That I, as a disabled person, was coming up with a plan B to make sure I could survive in the case of something.”

Marcella Genut, a student in Georgia, shared similar concerns. The 21-year-old lives with spinal muscular atrophy and uses a wheelchair. In high school, Genut practiced active shooter drills but said the protocols weren’t accessible. During the “hide” portion of drills, Genut and her wheelchair were always visible:

First of all, you’d have to move all of the desks, and, already in high school, I already couldn’t get around the room very easily, and having a wheelchair makes a lot of noise. The thing they stress about drills like that is to be quiet, but it’s kind of impossible when you, you know, you have machinery or something.

I think the best thing to do would be would be to evacuate me out of it, but we never practiced that… If the time did come it could be quite dangerous because we never practiced that.

Genut also required daily medications, which she was told had to stay in the nurse’s office. “I think talking to each teacher I had in high school and having the medication and things I would need in each classroom instead of just in the nurse’s office would [have been] really helpful,” she added.

It’s not just students with disabilities who are concerned about their safety. Teachers with disabilities also feel their needs haven’t been addressed. When tasked with the safekeeping of dozens of students, they want policies and protocols that help them protect those in their care, as well as themselves.

For Jessica Roberts, a former elementary school reading teacher from Arizona who took a break from teaching after having a baby, this means practicing drills outdoors as well as indoors. In addition to her teaching responsibilities, Roberts, who has a spinal cord injury and uses a wheelchair, worked as a playground monitor, watching anywhere from 60 to 100 first-, second- and third-graders with one other person.

“There was a lot of concern, especially because we didn’t have a lot of coverage outside,” she explained. “You’re going into a building, you’re going into an open classroom, but we didn’t have keys to lock those doors. So we pretty much had to barricade ourselves and I wonder how, even now, would we have barricaded ourselves in there?”

If students couldn’t get indoors, Roberts said there was a fence they could probably climb to run off campus. But that would only be an option for able-bodied students.

“It would have been run for your life, and that’s it,” she said. “Just run.”

As for protocol for herself, Roberts was able to get her classroom moved to the first floor, making evacuation easier. Before that, were there an emergency, she had to depend on others to carry her and her wheelchair down the stairs.

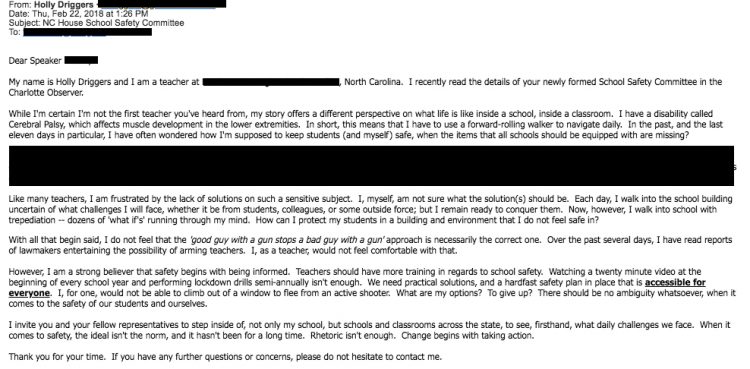

In North Carolina, Holly Driggers, a high school English teacher with cerebral palsy, is the only teacher at her school with a disability. “Our first priority is the students,” Driggers said, “just to make sure they are out of sight. But as far as specific instructions for me, I haven’t been given any, which is really unsettling.”

Driggers has windows in her classroom that students can climb out of should they need to evacuate. Driggers, however, would not be able to: “I sort of have resigned myself to the fact that if it ever did come to that, that the odds would not be in my favor, which is pretty scary to think about.”

Her plan: to hide in a cabinet once she’s ensured her students are as safe as possible. “I would try to do everything that I possibly could,” she said.

Driggers emailed her district’s representative, letting them know the drills in place are not sufficient for teachers and students with disabilities. She did not hear back.

Elizabeth Mintz, a high schooler with a disability in Levittown, New York, told The Mighty, the best thing schools can do for teachers and students with disabilities is listen to them.

Mintz, 15, lives with a physical disability that makes mobility difficult. While she feels she can follow most of the safety protocols her school has, she’s concerned she wouldn’t be able to evacuate quickly if in a classroom upstairs.

“I have nearly fallen down a set of stairs because I’m a bit slower on stairs than other students, and they tend to push and shove,” Mintz explained. “This has caused me to occasionally wonder if I’d be able to safely make it out of the building along with the able-bodied students if there were an actual emergency.”

When asked if she’s told educators her concerns, Mintz said she hadn’t, due to the way her school has handled other disability-related issues. “No alternative plan for emergencies has been brought up,” she said. “The plan I’ve followed has always been, ‘Do what the rest of the students do, and if you get pushed or shoved on the stairs and you fall or get hurt, oh well.’”

Additional reporting by Elizabeth Cassidy, Casey Chon and Haley Quinn.