Hans Asperger, Researcher Asperger Syndrome Is Named After, Had Ties to Nazi Party's Child Euthanasia Program

A new study published in the journal “Molecular Autism” on Wednesday has found a link between Hans Asperger — the doctor whose last name has been used to describe Asperger syndrome, a diagnosis on the autism spectrum — and the murders of children with disabilities in the 1940s.

Asperger is considered one of the first researchers of autism. His work described boys with “average” intelligence and language development who had difficulties with social and communication skills. In 2013, “Asperger syndrome” was removed from the DSM-5, the manual physicians often use to diagnosis autism, and replaced with the general term “autism spectrum disorder.”

Asperger was an Austrian pediatrician during the Nazi regime. Researcher and historian Czech Herwig noted that Asperger was not a part of the Nazi party but was involved in organizations affiliated with the party. Herwig said Asperger “publicly legitimized race hygiene policies including forced sterilizations and, on several occasions, actively cooperated with the child ‘euthanasia’ program.”

Asperger sent some of his patients to the Am Spiegelgrund clinic, which murdered hundreds of children deemed to be “uneducable.” At least two of the children mentioned in Herwig’s report were categorized by Asperger as too high a “burden” for their mothers.

“Ideas about what a good life is, whether some lives are worth more than others, and who counts as a contributing member of society, have always affected the way society treats people with disabilities,” the Autistic Self Advocacy Network (ASAN) said in a statement. “These ideas have always been violent and have always ended up killing people.”

Previously, Asperger was thought to be ambivalent toward Nazi party ideologies, meaning he wasn’t for or against, but Herwig stated his research gives a more detailed assessment of Asperger’s problematic role during the Nazi regime. According to Herwig, Asperger “managed to accommodate” himself with the Nazi regime and was subsequently rewarded with career opportunities.

In 1940, Asperger took a voluntary role in a commission whose purpose was to categorize children by their “intellectual abilities and prognoses.” Thirty-five children were given the label “uneducable,” which led to their deaths at the Am Spiegelgrund clinic. Herwig points out that Asperger did not have a direct role in these deaths, but shows the extent to which Asperger “cooperated with the regime’s murderous policies.” Herwig also states Asperger was under no obligation because the operation was considered illegal, even under Nazi rule.

“The narrative of Asperger as a principled opponent of National Socialism and a courageous defender of his patients against Nazi ‘euthanasia’ and other race hygiene measures does not hold up in the face of the historical evidence,” Herwig wrote.

The discovery of this information was shocking for many people in the autism community, especially those who used to identify themselves as having Asperger’s syndrome or being an “Aspie.”

“When I first read about Hans Asperger and this new information resurfaced about he and the Nazi regime, I was stunned, honestly,” Katelyn Decker, a member of The Mighty’s autism community, said. “It didn’t really click with me until I read and reread articles about his work and the research that has been done to fully understand what happened. Once it did hit, I was shocked and quite upset.”

Despite the revelation of Asperger’s participation in these heinous acts, ASAN said in its statement that these findings do not change the autism community. The essence of the community isn’t in an outdated term’s origin but in the people who comprise the community.

“While this latest news may be very distressing to hear, it doesn’t change who we are as autistic people, and it doesn’t change what autism is,” ASAN stated. “How others perceive our disability absolutely affects our lives, but we define autism on our own terms. We are primarily concerned with the experiences of our fellow autistic people, not what Asperger thought.”

The news about Asperger shook Decker to her very core, she said. But she’s always identified as an ‘Aspie,’ not because of the man but because it’s her way of defining autism on her terms.

“I will still refer to myself as someone diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome because that is a part of my identity,” Decker said. “It helps me to understand myself and helps the people around me to understand who I am and how I function.”

For others, it’s won’t be as easy to continue using the term, no matter how much they identified with it. “I do motivational speaking about my stuttering and Asperger’s ,and while I had gotten acclimated to referring to myself as an ‘Aspie,’ now I have serious reservations about that description,” Steven Kaufman, another member of The Mighty’s autism community, said. “I think effective from this point forward I will refer to myself as being on the spectrum or ‘high-functioning.’”

Angie Arcuri, also a member of The Mighty’s community, hasn’t made her mind up on using the term just yet, but she’s aware that “correct” terms and labels are debated within the autism community. Labels shouldn’t detract from the community’s overall needs, such as educating the public that autism isn’t an “undesirable trait” but rather a part of neurodiversity.

“The autism community is so divided on semantics and how words are used in regard to autism, and in regard to the way in which autistics are treated,” Arcuri said. “But I think it would be beneficial for all who are part of the autism community to be on the same page, to embrace who we are, and to embrace the fact that autism truly is a very large spectrum and we cannot get hung up on people’s use of words.”

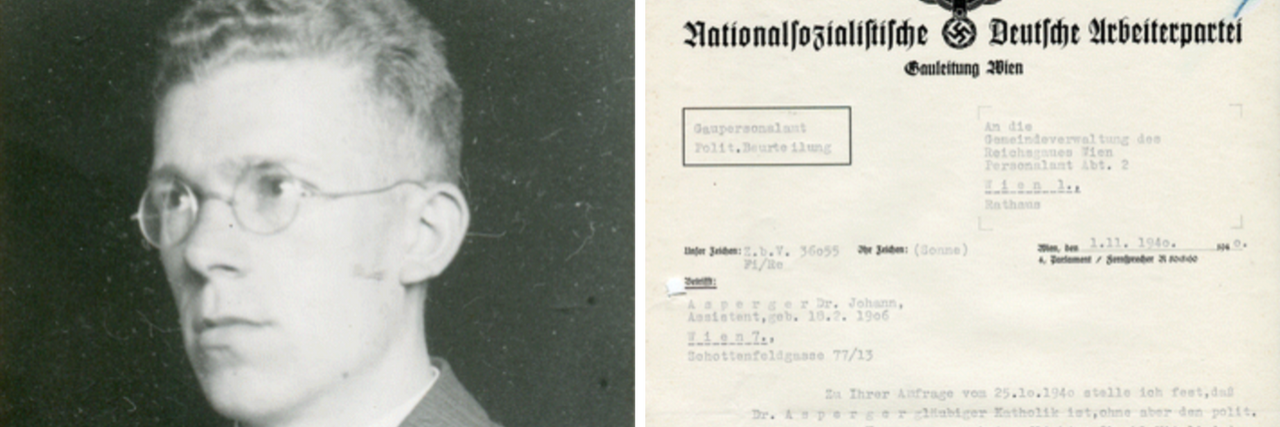

Photos via Czech Herwig/Molecular Autism