One of the most common myths about autistic people is that they don’t feel empathy towards others. As the wife of an autistic husband and mother of children on the spectrum, I want to help people understand where this mistaken belief comes from.

What is empathy? Put simply, empathy is the ability to understand what another person is thinking or feeling; but in reality, empathy is anything but simple. Autistic people can struggle with certain aspects of empathy, but does that mean they don’t experience it at all? Many people still believe they don’t, and imagine autistic people have no ability to make emotional connections or form meaningful relationships. I’m glad to say that they couldn’t be more wrong.

Join the conversation by answering the question below:

Autistic people are often the kindest, most compassionate individuals you could hope to meet, deeply committed to their friends and family, with an intense spiritual connection to the world around them. So where does the misconception that they’re emotionless, robotic loners come from? The answer is from a combination of the nature of autism itself and the nature of empathy, both of which are highly complex subjects. To keep things simple, this post focuses on the three main aspects of empathy – cognitive, affective and compassionate — and how autistic people process, experience and ultimately express them.

Cognitive Empathy

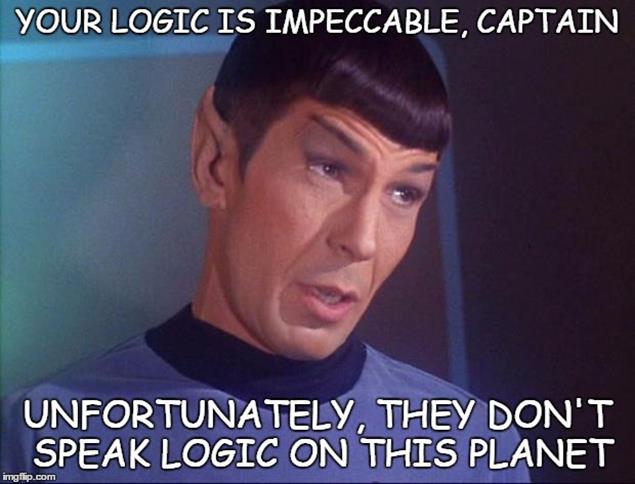

This is the mostly conscious ability to understand what other people are thinking or feeling. It’s a thought process that allows you to work out what people really mean when they say something vague, or which emotions they’re experiencing when they act in a way you find confusing, and this is the part autistic people can really struggle with.

Anyone who lives with autism (whether they’re autistic themselves or know someone who is) will understand how difficult it can be for people on the spectrum to predict other people’s intentions and behaviors without specific directions. Put another way, when you talk to autistic people, it really helps to say exactly what you mean, because they don’t do “implied.”

A classic example of this happened only last week, when my son’s girlfriend told him “I’ve just left work; meet me at the end of the road.” Now, it was clearly implied that since she’d just stepped out of the office, she intended to meet him at the end of the road she works on, but to Aidan this was anything but obvious.

Twenty minutes later she was still waiting there for him, while he stood patiently at the end of the road she lives on, which seemed like the most logical meeting place to him since they’d met there several times before.

The ability to consciously recognize what other people are thinking and feeling is known as “theory of mind” (often abbreviated to ToM), while being unable to do this is known as “mind-blindness,” both terms you’ve probably come across if you’re part of the autism community. Mind-blindness is one of the most common traits a health professional will look for when diagnosing someone with autism, and its effects definitely work both ways.

Autistic people may assume everyone feels the same way they do about things and are motivated by the same interests and passions, resulting in endless discussions about their special interests. They’ll also believe that because they know something, other people automatically do too, and this can lead to all kinds of miscommunication. When my son Dominic was young we almost lost him to acute double pneumonia because he didn’t tell us he was in excruciating pain every time he coughed. When I asked him why he hadn’t mentioned it, he said simply “I thought you knew.”

Affective Empathy

This is an automatic, unconscious response that allows you to feel what other people and other living beings are feeling, and is something autistic people definitely possess.

You’ll often find people on the spectrum who feel deeply connected to all kinds of animals, and the bonds they form with creatures who aren’t restricted by the endless social rules human beings follow can be quite remarkable. When it comes to this kind of empathy, rather than having a lack of it, autistic people can often have too much – a condition known as “hyper-empathy.” They can be incredibly sensitive to different atmospheres, picking up on the slightest tension when people are interacting and becoming increasingly upset if things escalate.

Hyper-empathic people find that even the thought of another’s suffering causes intense emotional, psychological and even physical distress. Since processing this intense level of feeling can be really difficult for them, they’ll often go into meltdown for what appears to be no reason, but is in fact something very real. Another way this can manifest is in the extreme personification of objects, which is a posh way of describing the overwhelming emotional bond some autistic people feel towards everyday things like rocks or paperclips.

You can find endless examples of personification in our language (the sun is smiling down on us/the thunderclouds look threatening etc.) and also in our culture, with films such as “Toy Story” being hugely popular, but what I’m describing is more than that. Autistic people can become incredibly distressed if they feel, for example, that a particular hairbrush or crayon isn’t being used often enough because it might feel left out. I know how that may sound to someone who’s unfamiliar with autism, but trust me, if you’re autistic this stuff often really does make sense.

Compassionate Empathy

This allows you to both understand another person’s situation and be motivated to help them if they’re in some kind of distress. Again, autistic people have no shortage of this at all, even though they can struggle to offer the right kind of help sometimes. Many autistic people are highly motivated in standing up for things they believe are unjust, and in the struggle for animal rights, an equal society and a better environment, you’ll find some of the most passionate voices can be the autistic ones.

Need to share something honest? Downloading our app makes it easy to post Thoughts and Questions on our site.

People on the spectrum don’t see the same boundaries as non-autistic people do, which is a huge bonus when it comes to thinking up new solutions to seemingly unsolvable problems and leading the way to a better world for everyone. But there are often challenges in the way autistic people express their desire to help when it comes to emotional support. Since they tend to be very logical and want to solve puzzles and problems, they can come across as very black and white in their thinking and may miss the more subtle emotional needs of others in a situation.

Autistic people often don’t like to hug, or they hug too tightly, which is a natural way for non-autistic people to show empathy, and this can help perpetuate the myth that they’re uncaring. Putting your hand on someone’s arm or your arm around their shoulder when they’re upset are both instinctive gestures for neurotypical people, but can be beyond awkward for autistic people who struggle to pick up social cues as to how much physical contact is appropriate in any given situation.

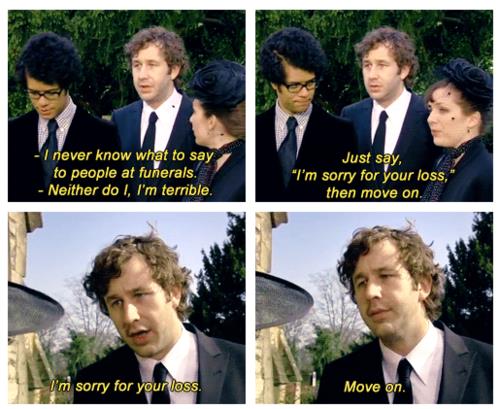

Happy celebrations like weddings and birthday parties can be incredibly difficult to navigate if you’re autistic, as can emotionally draining gatherings like funerals. Learning to “say the right thing at the right time” can be extremely confusing and lead to all kinds of misunderstandings, but even though they might get things wrong, they really do care, and are trying their best to be supportive.

So those are the basics of empathy, and how autistic people process and express them. I’ll leave you with a real-life example of one autistic man’s version of compassionate empathy which pretty much sums up why I no longer ask my husband for fashion advice.

I’d been dogged by some very serious illness and injuries for several years and as a result had put on quite a bit of weight. We were going out, and I squeezed myself into a pair of jeans I hadn’t worn for ages but was unsure about whether or not to wear them in public. I mentioned to my husband that I felt a bit uncomfortable about how my legs looked. Instead of the standard “You always look beautiful to me, darling,” reply I was hoping for, he spent way too long staring at my thighs and came out with the ever-so-helpful statement “Yes, they are pretty big. Just wear a long coat.” Sigh.

Getty image by Holly Powers.