Learning to Celebrate the Small Victories After Becoming Disabled

“OMG, I can’t deal with this anymore!” (after waking up in pain again)

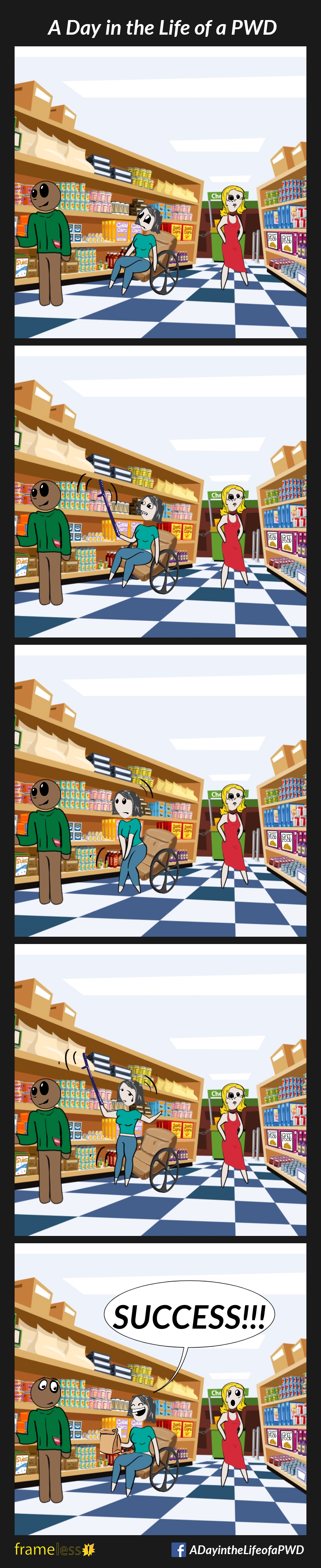

“Sigh. I’m so over this!” (after several unsuccessful attempts to reach for something)

“Dammit! I’m such a f-ing cripple!” (after dropping 14 things in one afternoon)

When I’m in the midst of angst or depression over my disability, I become mired in self-pity and dread for the future. I worry that if I feel such pain now, how will it be 40 years from now when I’m in my 80s? Then I contemplate what 40 more years in this body will be like, and it freaks me out.

I was once able-bodied, and when I dwell about all the basic things I’m unable to do now, it makes me sad. When I can’t do something despite my fervent attempts, it makes me angry. And when I think of the extra time effort it’s going to take to do the same thing my able body would have done quite easily, it makes me want to give up before I even start. If allowed to do so, my imagination will run zombie apocalypse or disaster scenarios. I’ll torture myself with images and scenes of myself unable to survive because of my disability. I can wind up wallowing in grief over my loss and fear for my vulnerability.

I was once able-bodied, and when I dwell about all the basic things I’m unable to do now, it makes me sad. When I can’t do something despite my fervent attempts, it makes me angry. And when I think of the extra time effort it’s going to take to do the same thing my able body would have done quite easily, it makes me want to give up before I even start. If allowed to do so, my imagination will run zombie apocalypse or disaster scenarios. I’ll torture myself with images and scenes of myself unable to survive because of my disability. I can wind up wallowing in grief over my loss and fear for my vulnerability.

How easily I forget where I began and what I have overcome. How easily I overlook each tiny step that has delivered me to where I am today. How easy it is to focus on the impossible and forget the possible. About this time nine years ago, I had just come out of a six-week coma. I was paralyzed, unable to speak, had diplopia and opthamoplegia, and a tracheostomy. I scored a 3 on the Glasgow coma scale, and the prognosis was not promising. But I eventually “came to” and spent 18 months in the hospital, then 2-and-a-half years in rehab.

Because my throat was still paralyzed, they thought I would have to have a tracheostomy for the rest of my life. It came out 11 months later. Because my feet were pointer-flexed, they thought I would never walk again unless my feet were amputated and I wore prosthetics. After tendon release surgery and a year of rehab, I was on my feet again, my own feet! As a result of the coma and bed confinement, both my shoulders are frozen and I have scoliosis and kyphosis. I also get abdominal spasticity, which is the main reason I need to use a wheelchair. It was thought that I would have to go to a long-term care home. Instead, I live a relatively independent and autonomous life in a Family Care house.

How did I get through all that? Sometimes it took a conscious effort to “be brave” and fight through the pain and refuse to give up. But to be honest, it was mostly just about living and learning to live in a new body. I got sick of being dependent. I got sick of waiting. Waiting for assistance with simple tasks, waiting for meals, waiting to do what I wanted. I began trying to do things for myself, getting things for myself, accomplishing things on my own. It became my way: always try it myself first before asking for help. I didn’t realize how important that was until I began remembering where I started. Now and again I am pleasantly surprised to discover that I can do something I wasn’t able to do before, all because I just kept trying before asking for help.

I weep for the woman I was before: immobile, unable to communicate, wracked with pain and discomfort, isolated, lonely and utterly dependent. But this helps me celebrate the woman I am today: independent, autonomous, strong, resilient and always growing. When I take the time to acknowledge and honor all the baby steps, all the little accomplishments, all the progress I’ve made, my angst and depression over my disability dissipates and is replaced with pride and confidence.

The next time you feel like you can no longer cope with your disability, I invite you to take a moment. Remember how you got here. Celebrate the tiniest of accomplishments, because those add up. Delight in the smallest of discoveries, because they matter. And allow yourself to be human, not a superhero or poster child. Just a normal human, trying to live your life in the best way you know how.

Getty image by Antonio Guillem.

This article originally appeared on A Day in the Life of a PWD.