Why Ali Stroker's Tony Win Is a Victory for People With Disabilities

Sometimes the news isn’t as straightforward as it’s made to seem. Karin Willison, The Mighty’s disability editor, explains what to keep in mind if you see this topic or similar stories in your newsfeed. This is The Mighty Takeaway.

On May 31, I saw Ali Stroker play Ado Annie in Daniel Fish’s dark reimagining of the Rodgers and Hammerstein classic “Oklahoma” at the Circle in the Square Theatre on Broadway. Just over a week later on June 9, she became the first performer who uses a wheelchair to win a Tony Award, for Best Featured Actress in a Musical.

We cay-n’t say no to Ali Stroker!#TonyAwards pic.twitter.com/d8f80ux4tP

— broadway.com (@broadwaycom) June 10, 2019

In her acceptance speech, Stroker said, “This award is for every kid who is watching tonight who has a disability, who has a limitation, who has a challenge, who has been waiting to see themselves represented in this arena. You are.” As someone who was once one of those kids, I want the world to understand the impact of a person with a visible disability winning the most prestigious award in the theatre world, and succeeding when so many of us have been told there was no place for us there because of our differences.

Stroker’s performance, which she also showed off during the Tony Awards broadcast alongside the rest of the cast, has been lauded by numerous media outlets, but most if not all the reviewers have been able-bodied. I want to share a different perspective as someone who loves musical theatre and has attended hundreds of professional and amateur shows over the years, yet never got to see someone like me on stage.

I went into the Broadway production of “Oklahoma” without knowing much about its unconventional approach to the material. Director Fish reveals the disturbing underside of what is usually a cheerfully sanitized story about the American frontier. The “hero” Curly now has a distinct sleaze in his swagger, heroine Laurey is conflicted about the narrow role her insular world pushes her to accept, and villain Jud Fry manages to be both sympathetic and someone you know would be featured on a true crime podcast. The orchestra has become a seven-piece country band, and the dream ballet a provocative performance art piece. This is not your grandmother’s “Oklahoma.”

In a production already smashing stereotypes, it makes sense Fish would decide to challenge audiences’ expectations further with an Ado Annie in a wheelchair. But casting Stroker was not a stunt, nor an attempt to make the story even darker — quite the opposite. Her raw, powerful singing and cheeky attitude gives the show the humorous punch it needs to avoid becoming mired in its more depressing elements.

I paid careful attention to all the elements of Stroker’s performance — not just her singing and acting, but how she moved within the space, how she interacted with the other actors and how they incorporated her into the choreography. I noticed the expressive ways she used her wheelchair to add to the movement and dancing; she even popped wheelies during certain high notes and exciting moments.

David Rooney of the Hollywood Reporter said Stroker maneuvers her wheelchair “like an extension of her body,” which he seemed to find surprising. But wheelchairs are legs for those of us whose legs can’t carry us, so it’s natural for an actress to convey her character through the spin of a wheel in the same way another might use the tap of a foot or a swing of a hip. It’s just something few people have ever seen before, because actors with disabilities are so rare in theatre. In fact, Stroker became the first wheelchair user to ever perform on Broadway just four years ago, in “Spring Awakening.”

Stroker’s role in “Oklahoma” is groundbreaking in large part because it defies stereotypes about disability, particularly the false assumption that people with disabilities cannot have sex or relationships. Women with disabilities in particular have very few role models to show us that we are deserving of pleasure and happiness. But as Ado Annie, Stroker sings boldly about sex and makes out with two different men, and she does so with joy and without shame. As someone who has struggled with my body image my whole life, who has almost never felt beautiful or sexy on the outside because of my disability, I found her performance refreshing and tremendously empowering.

Every interaction between Stroker and her co-stars models positive physical contact between disabled and able-bodied people — how to embrace a seated person while avoiding the awkward shoulder half-hug, how to dance with someone in a manual chair and how to express passion when a partner is on wheels. By the final bows, every person in the audience will have seen that people with disabilities have the same desires for sex and relationships as able-bodied people and can be desired in return. Her character even gets caught up in an epic Broadway love triangle — now that’s equality.

Performers with disabilities tend to be rewarded for how inspirational they can be, with “inspiration” narrowly defined as spiritually uplifting and pleasing to the sensibilities of ignorant non-disabled people. In the disability community, we call this “inspiration porn,” and most of us are sick of it. I always feared if we ever got a disabled musical theatre star, they would achieve fame through such a role, some rousing story of overcoming and becoming a saintlike hero who could do no wrong — and have no fun. I’m beyond thankful it’s wholly impossible to apply any such sentiment to Stroker’s Ado Annie. She is raw and frank and real, and her complete lack of pandering to disability stereotypes makes her Tony win all the more powerful. Nobody can claim she won because voters felt sorry for her. She earned this fair and square.

Stroker didn’t need to “overcome” her disability to succeed on Broadway, she needed to own it — and she does. She also needed an opportunity — someone to recognize how her wheelchair and her identity could add meaning to the story. Fish and his production team did, and they should be commended for it. I hope and believe her Tony win will pave the way for more opportunities for stage actors with disabilities.

With that said, we must all work to ensure Stroker is the first of many actors with disabilities to achieve success on stage. We must avoid a repeat of the Marlee Matlin Oscar win, where one disabled performerr continues to have a successful career but through no fault of her own becomes a token, someone the industry can use to claim it’s inclusive while other disabled actors and stories about disability remain unheard and untold. Just as Fish’s “Oklahoma” exposes the dark side of the frontier, I believe to achieve lasting change we must address the dark side of the theatre business, the pervasive prejudice actors with a disability or any kind of difference face in a discriminatory industry.

Two of my best friends are professional actors, and they have told me how psychologically brutal the audition process can be, even for performers like them who do not have physical disabilities. Talent often means far less than it should; a person can lose a role for being an inch too short or tall, or for not having the “look” a director wants. Sexism and ageism are pervasive in the industry, and although race-inclusive casting has increased, racism remains a major issue. Ableism is ever-present, but almost never acknowledged even when Hollywood and Broadway are called out for other forms of discrimination.

When disabled actors speak out about able-bodied actors being cast as disabled characters, they are often dismissed with flippant comments like “any actor should be able to portray a disabled character; it’s called acting.” But when they audition for characters not specifically written as having a disability, they are also often rejected, even if nothing about the character would preclude them playing the role. I want to believe “Oklahoma” will change all that by showing people with disabilities can play all kinds of characters, and even a character we’ve always imagined as able-bodied doesn’t have to be. But for that to happen, we must fight for inclusion at all levels, from school plays to Broadway and onscreen. How much talent are we missing out on because young people who look or move or think differently are never given a chance?

My story is an example of what often happens to aspiring performers with disabilities. As a kid I had two passions in life — writing and musicals. I spent years performing in shows, taking voice lessons and learning adaptive dance methods while also battling through grueling daily physical therapy for my cerebral palsy. But in high school, a choir teacher who I believed to be an understanding ally discriminated against me when casting the spring musical. Despite a stellar audition, I did not get a main role. Devastated, I asked the teacher why. Was I not good enough? If he had said I wasn’t, it would have been painful to accept, but fair. But his reply stunned me.

“Oh you’re good enough. You’re very good. But what would we do with your wheelchair? It would be in the way.”

His words have haunted me for over 20 years. That day I learned it didn’t matter how talented I was, my disability would always be seen as a barrier. Worse still, the people who usually supported me — including my own mother, who had always relentlessly fought for my rights — just wanted me to let it go. There was nothing anyone could do, she said, but what I heard was the battle wasn’t worth fighting because I didn’t belong in the theatre anyway.

So I stopped performing. It’s the only time I’ve ever given up, the only thing I’ve ever let my disability — or rather, people’s perceptions of it — stop me from doing. I’m happy with my chosen career, but I do sometimes wonder about the road not taken. I imagine myself having become a director, playwright or lyricist and I wish I’d had someone to show me those paths were open to me.

Back then there were no Broadway stars in wheelchairs. There was no one I could point to and say to that teacher, “You’re wrong.” But now we have Ali Stroker. Now all the little girls with disabilities who dream of being on stage have someone they can look up to, someone who is showing the world you can act and sing and dance in a wheelchair. She is living proof that when somebody tells you that you can’t do something because of your disability, they are the ones lacking in imagination. Her wheelchair is not “in the way,” and it never will be. Neither is mine. Neither is yours.

Stroker’s Tony win is a victory not just for her, but for the disability community. Now it’s up to all of us, disabled and non-disabled, to fight discrimination and lift up talented people who look and move and perceive the world differently. Directors, you can be the change by casting qualified disabled actors in all kinds of roles. Producers, fund the work of disabled directors and writers who create plays and musicals that reflect their lives — some focusing on disability and others where it’s just a small part of a character’s story. All cast and crew, make your production a safe space for professionals with visible and invisible disabilities, chronic illnesses and mental health conditions to be open about their experiences.

One in four Americans have disabilities. If we were fairly represented in the arts, there would be disabled Tony, Oscar, Emmy and Grammy contenders every year. Ali Stroker’s motto is “Make your limitations your opportunities.” With people like her blazing a trail, I believe we can.

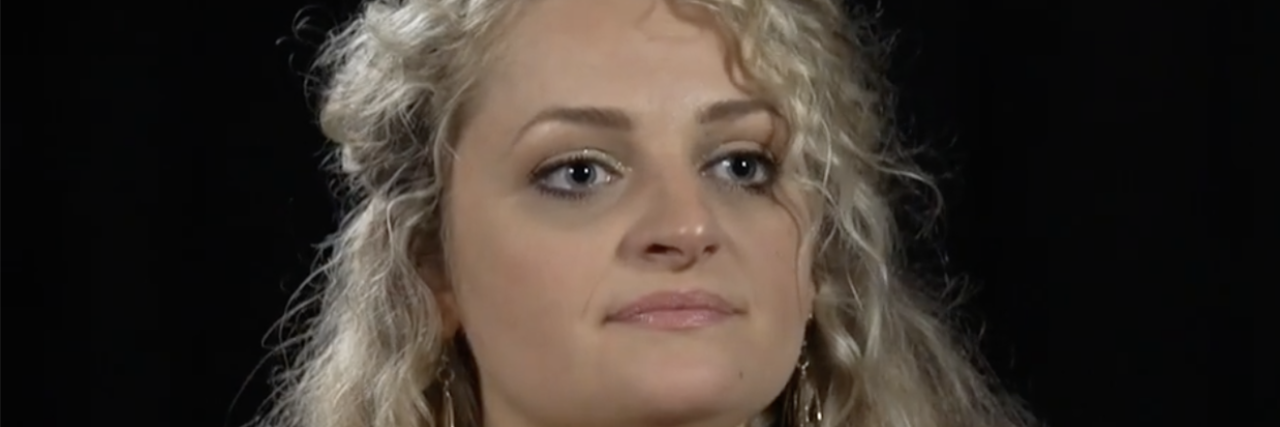

Image via Creative Commons/The Tony Awards Youtube Channel