What Karen Killilea Meant to Me as Someone With Cerebral Palsy

The world recently learned that Karen Killilea, who helped change how society views people with cerebral palsy and other disabilities, died October 30, 2020 at the age of 80.

When Karen was born prematurely on August 18, 1940, she weighed less than 2 pounds and was not expected to survive. She was later diagnosed with cerebral palsy at a time when people with disabilities had no rights and few opportunities. But rather than viewing her condition as tragic, Karen’s mother Marie fought for her to get medical care, attend school and find a place in the world. Karen went on to have a 40-year career as a secretary at a retreat for Catholic priests. She lived independently for most of her life, only spending the last few years in a nursing facility.

Karen was the subject of two bestselling books written by her mother, “Karen“ and “With Love from Karen.” They are the lens through which all of us who did not know her personally viewed her life. But were they her truth, or someone else’s?

A few years ago, I decided to write about Karen. I want to share an updated version of that article with you, to honor her while illuminating the limitations of the stories other people tell about us.

— — —

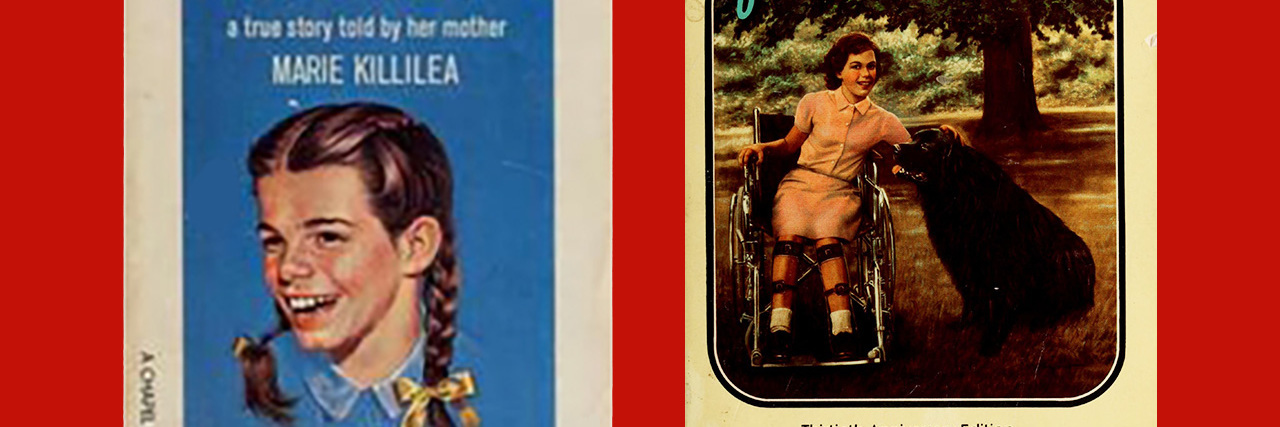

When I was about 7 years old, I found a paperback copy of “Karen” by Marie Killilea on my parents’ bookshelf. The cover showed a little girl with long red pigtails and a big smile. She was “the girl who lived a miracle!” The back cover featured her words in big letters: “I can talk. I can walk. I can read. I can write. I can do anything!” She was a little girl with cerebral palsy. She was like me.

I immediately wanted to know everything about her, this girl who almost shared my name. Almost 40 years separated her birth and mine, but there were so many parallels between our stories. Karen Killilea was born prematurely, whereas I was deprived of oxygen during birth, but the end result was the same for both of us: cerebral palsy. The words the doctors told our parents were, too. “She will never walk, or talk, or feed herself.” “She’ll be severely mentally retarded” (that was the term they used, and it was just as offensive then as it is now). “You should put her in an institution and go on with your life.” Thankfully, her parents and mine refused to believe those words. They believed we had potential. They searched the country for answers, until they found hope.

When Karen Killilea was a child, there were no laws guaranteeing children with disabilities the right to an education. She was fortunate that a parochial school was willing to accept her. I was born after the Individuals With Disabilities Education Act had passed, so I had a right to go to school, but that didn’t mean it was easy. My mother had to fight for me to be included in regular classrooms, and I spent a few years in private school because the local middle school wasn’t wheelchair accessible.

Karen and I were both very intelligent, but frustrated with the physical limits that had been placed upon us. We both had some friends, but were still lonely, and found comfort in our beloved dogs. We both spent a lot of time in physical therapy.

Karen had learned to walk, the Holy Grail of human accomplishment as far as my mother was concerned. She wore heavy metal braces that locked her knees in place, and would swivel her hips to walk. By the time I was born, plastic foot and ankle braces were the new technology. They are a major improvement over metal braces, but still ugly and cumbersome. I had to wear shoes that were a few sizes too big and felt like a clown. My parents made me do physical therapy for at least an hour every single day. I only got my birthday and Christmas off. I felt miserable and trapped.

I remember reading “Karen” and being struck by how much her mother was like mine. Marie Killilea believed in her daughter, no matter what. She also pushed her, sometimes to the breaking point. I often wondered how Karen felt about her braces and therapies and endless trekking from one specialist to the next. Her mother portrayed her as almost entirely good-natured and cooperative. I judged myself harshly for not being the same way.

I think my mother hoped that Karen Killilea would inspire me to keep going, to believe I could accomplish everything she had and do it with a smile on my face. I’m not sure Karen’s story changed my mood much, but she did help me feel like I wasn’t alone. Somewhere out there was a girl with my name who had been through the same things I had. She was my soul sister, my older twin. I wondered what happened to her after the book ended.

A few years after reading “Karen,” my life changed tremendously. I learned to walk! I could use a makeshift walker made out of an old chair with wooden skis on the bottom, take a few steps on parallel bars, and a few steps with a regular walker. My parents were thrilled. I tried to be. Every step was exhausting, and I often fell and hurt myself. I was told it was a huge accomplishment, that I should be so proud. I couldn’t understand why I wasn’t happier about it, like everyone else.

In sixth grade, I was in the school library when I spotted a book called “With Love from Karen” in a rack full of paperbacks. The cover showed a girl whose face had become very familiar to me. It was “my” Karen. The book was a continuation of her story! I wondered why my mother hadn’t told me about it. I checked it out immediately.

When I brought it home from school, my mother’s reaction wasn’t what I expected. She said she didn’t want me to read it — or I could, but I wasn’t allowed to read the last few pages. She disappeared into her room and returned with her own copy of the book. The last several pages had been torn out. She took the library copy and made me return it the next day.

I couldn’t understand her behavior. She had promised to never censor what I was allowed to read. What could be so terrible in a book about Karen Killilea that she’d change her mind? Of course, I did what kids do when they’re told they can’t read or watch something. I found a way to read it anyway. My school aide didn’t know about my mother’s objection to the book, so she was all too happy to hand the library copy back to me. I sat in the nearly empty library between classes and read the last nine pages.

In that moment, Karen Killilea transformed my life. Her voice, mostly filtered through her mother throughout the first book, rang out loud and clear in the final pages of its sequel. One day in the garden, Karen broke down in tears, afraid to admit to her mother how she had been feeling. She had begun to realize that while walking with her braces and crutches was slow and painful, using a wheelchair gave her freedom. Here are her words.

“I’m so dependent in braces. I have so much more freedom in the wheelchair. Now — should I give up the braces and crutches — forevermore? Should I use a wheelchair exclusively? Should I?”

Her mother listened, but refused to state her own opinion, and said she wanted Karen to decide for herself. Then Karen said, “I’ve done some thinking about the 20 years you and Daddy and the kids have worked getting me to walk. To say nothing of the expense.” She said she feared being considered a failure.

Her mother replied, “We did not put 20 years into getting you to walk. Whatever we put in was to get you to your maximum potential for independence. Walking was never an end in itself — rather a means to an end. What you have to decide, is whether now, and in the future, walking will best serve that end.”

Karen was still struggling to decide, so she made a list of pros and cons on a piece of paper. After much thought, she said:

“I am going to ‘graduate’ from crutches and ‘commence’ in a wheelchair!”

Then she showed her mother the list. Under braces and crutches, she had written the words prison and pain. Under wheelchair, she wrote freedom. Mother and daughter embraced, as years of unspoken feelings and tension melted away. Then Karen said the last words she ever spoke publicly:

“No more will I be a drab, slow little sparrow that hops around with his head down. I’ll be free, really free. I’ll be an eagle with my face to the sun.”

The instant I finished reading, I knew why my mother had wanted to hide those pages from me. I knew Karen was right. For her, and for me, walking was painful and exhausting. It didn’t give us liberation or independence. Only a wheelchair could do that. I knew I couldn’t tell my mother this truth I had learned, but it didn’t matter in that moment. I knew, and I could keep the secret close to my heart, and be comforted in the knowledge that my feelings were not wrong.

It took a few more years, but my mother eventually accepted that using a power wheelchair was my path to independence. She became involved with the disability rights movement and learned to embrace disability as a difference rather than a limitation. I lost her to cancer far too soon, but I am grateful for everything she did. Even when she made mistakes, she only wanted the best for me.

I always wondered why Karen Killilea never chose to tell her story. I looked her up online many times over the years, hoping to find a news story, a social media profile, something. I found very little, aside from a quote attributed to Karen that was shared in a now-defunct Yahoo group for fans of the books. (Its Facebook continuation can be found here.)

According to this document, Karen said:

“I’m amazed that people are still so interested in me. But the person they come to meet doesn’t exist now and truthfully, never did!” She goes on to say, “I love my mother, but never forget that I didn’t write those books; she did. I was only the object of her books. No, I’m not going to write my own book. I am a people person, but I also like my privacy.”

That glimpse, that small window into Karen’s mind tells me so much. To someone who has lived it, her words speak volumes. I believe I know why she never told her story.

I think Karen believed the world had a certain image of her that she could never live up to — that perfect, perky little girl who took whatever adversity was thrown her way with a smile. She is frozen in their minds as innocent, saintly. How could people accept the real Karen, the adult Karen who had opinions and desires and aches and pains and wrinkles all her own? How would they have reacted to the truth of how she felt about her childhood and her mother’s sanitized version of her life being turned into a bestseller?

There’s a term the disability community uses now to describe the way Karen Killilea was portrayed in “Karen” and “With Love From Karen” — inspiration porn. Inspiration porn treats a person with a disability as a symbol, a prop to make non-disabled people feel better about their own lives. Inspiration porn stories are usually told by non-disabled people without the input of disabled people, and depict us in a one-dimensional manner that incorporates various stereotypes and assumptions about how we “should” think and act and be.

As a child, I felt such a kinship with Karen, but couldn’t understand why she was so relentlessly cheerful while going through what I knew to be physically and emotionally painful experiences. I couldn’t see that “Karen” was a character her mother created to tell a story. The real Karen was never that person. And when she came into her own, when she made a choice that went against the heartwarming “miracle” narrative, her story ended, as far as the public was concerned. She wasn’t inspirational enough anymore.

To be clear, Karen’s life was genuinely inspiring. Her family blazed a trail for disability rights and inclusion while facing a level of ignorance and prejudice we can hardly imagine today. The disability community would not be where we are today without Marie and Karen Killilea. But it’s also important for us to recognize that the way they talked about disability then is not how we should be discussing it now. People with disabilities need to be centered in the narrative. Nothing about us without us. We need to tell our own stories that convey the fullness of our humanity — our strengths and our faults. We don’t have to be saints to deserve equal rights.

As I grieve for Karen, I wish more than anything that I could have known who she really was. I wish I’d been able to meet her, to bring my Newfoundland dog to the nursing home where she spent her last years and see her wrinkled hand, twisted like mine, pat Daisy’s furry head. I wish I could have looked into her eyes just once and whispered “thank you.”

Thank you, Karen, for being a light when I desperately needed one, for fighting to be heard and telling the world it’s OK to be disabled. I wish you had told your story in your own words, no matter what people might have thought about it. But you didn’t, as was your right. You chose to live a quiet but full life by all accounts, filled with friendship and love. You had a long career. You made it to 80 years old, bringing hope to many of us with cerebral palsy who wonder how the complications of our condition could affect our lifespan. You did enough. You were enough. And I’ll forever be grateful to you. So fly to the sun now, eagle. Fly away in power.