Creating Opportunities for Blind Students in Higher Education

About 11 years ago, I arrived in the United States. I remember carrying my violin and a suitcase full of hopes and dreams throughout the Houston airport. I was so ready to conquer the world. I could feel my confidence and enthusiasm flowing through my veins. English is not my first language, but with years and years of going to a bilingual school, I told myself it was going to be bliss.

Two years later, a high school diploma, and lots scars from lessons I learned, I arrived at college. Being a 17-year-old woman, about 107 pounds, 5 foot 4 inches tall, Hispanic, and an international student it automatically put me in a bracket called “different.” Partaking of the so-called group “different” helped me to explore, learn, discover and live what others in that group bring to and need from this earth.

About two years ago, I went to an art exhibit at the Aspen Museum. “Bound and Unbound” by Judith Scott was an exhibit that changed my life. Judith Scott (1943-2005), whose career spanned just 17 years was a vibrant artist at Oakland’s Creative Growth Art Center, where she produced a remarkable body mixed media sculptures. Her powerful, complex forms of art were creative avenues of expression for her as someone with Down syndrome. I remember standing in the exhibit and thinking of how few resources we have for people with physical and mental conditions to express themselves, or for them to find their full potential.

Not too long after that, my father-in-law started to develop an eye condition. My father in law, a well-educated person, lover of books, and a local artist was being limited and forced to discover or even create new avenues of expression to keep up with his day to day life due to his vision condition. This family scenario inspired me to do research on blind and vision impaired people, but especially on blind and vision impaired students who seek higher education.

During the research for this paper, I went back in time to my first years of college. I remember struggling to learn American culture, American cuisine, but above all American education. I remember being desperate for help to find resources that would lead me to my goal. Now just take a second and imagine the same scenario but if I was also vision impaired. I recognized that it would be a lot different.

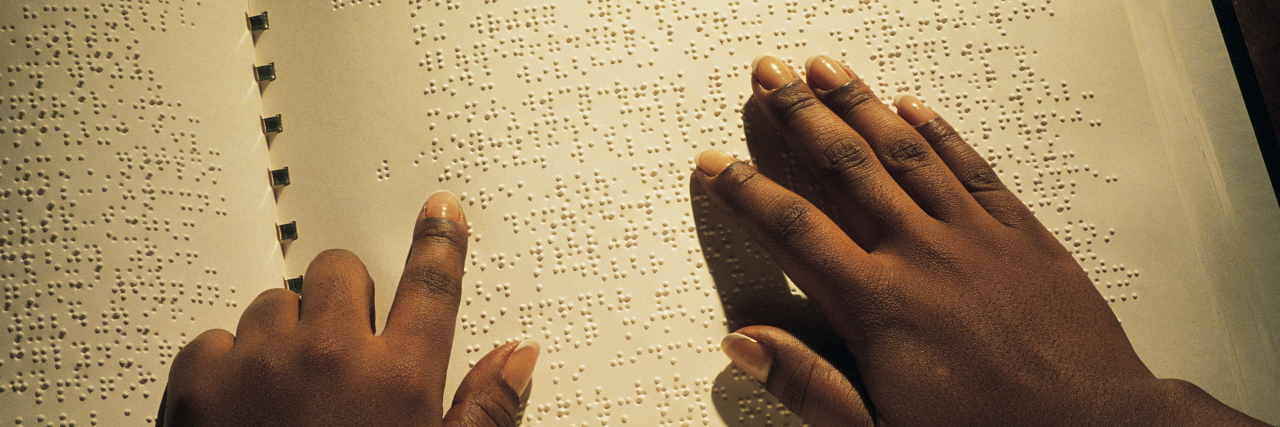

According to the American Foundation for the Blind, children with visual impairments need to change the way they obtain information about the world around them, and have limited opportunities to learn through observation of visual elements in the school curriculum and elsewhere. This means that the vision impaired student does not only have to learn the regular classroom studies, but also additional specialized skills. Some of these special skills include: technology and computer proficiency (computer equipment and screen reader programs), literacy skills (reading and writing with Braille, large print, optical devices, among others), age-appropriate career education, safe and independent mobility (use of long canes and other mobility tools), social interaction (understanding body language and other visual concepts), and independent living skills (personal hygiene, food preparation, money management, among others). These are already challenging skills for non-visually impaired students, but not impossible for either group.

When students are enrolled in a public or private school, they have people who are supposed to advocate for them such as special education teachers, parents, mainstream classroom teachers etc. But once vision impaired student leave those “controlled” environments, they need to become their own advocates for their physical and academic well-being. Of course this can be different for each family, but the goal is to have independent students with full social inclusion, and to achieve this independence is key.

According to the National Federation of the Blind and their statistics for 2015, blind people tend to attain lower levels of education than the general population. Only 14.9 percent of visually impaired students attained a Bachelor’s degree or higher, compared to 30 to 32 percent of the general population. This means the blind and vision impaired community’s Bachelor’s graduation percentage is less than half that of the general population.

After seeing this data, I began a couple of investigations and did some interviews in the community to see why the percentages drop so much for blind or vision impaired students to complete any type of higher education. I took an assignment for one of my Master’s classes and went to different local libraries and institutions to see how many useful resources I would find. Unfortunately, I did not find any physical books on the shelf at a local library.

I asked the librarian at the call center how she would direct a blind or vision impaired patron who needs to write an academic paper. She responded that the local library could help with finding resources for the assignment, but the items needed had to come from the state library, and unfortunately would arrive past the due date for the assignment. Also, she gave me a very good suggestion to recommend that blind and vision impaired students to set up a one-on-one meeting for 30 minutes with a librarian. At the end of our interview, she was so grateful I helped her her see the need of academic resources for blind and vision impaired people. The interview was her first time dealing with such a case.

During the month of February, I visited my home country, El Salvador and I went to an extraordinary non-profit group that supports all kinds of disabled people. Since the social inclusion of people with disabilities is not a priority to the current or previous government of El Salvador, many non-profit groups have started to create new avenues for education and social integration.

When I visited this non-profit organization, I was amazed at the level of passion, from the teachers to the students. Each room was not equipped with sophisticated or even basic tools to facilitate any kind of education for the students. Each teacher creates their own Braille with liquid glue. They also create multiple activities to nourish each student according to their disability, such as a sign language choir, individual and group physical therapy, and multiple health fairs to educate families and caregivers on hygiene and social events for the students with disabilities. I was so grateful to see that this non-profit organization is helping every family or person who has any type of disability. This non-profit organization really puts to shame organizations that have an incredible amount of funding, but they do not use funding for its specific purpose.

As an advocate for blind and vision impaired people, I ask myself what happens to these kids when they can’t or do not know they can advocate for their rights and seek higher education. How can we advocate for social inclusion? How can we start creating resources for blind and vision impaired students to reach their maximum potential? The answer is simple — advocate! Let’s become advocates and creators of new avenues of expression and education for blind and vision impaired students. Let’s build a revolution that’s blind and vision impaired accessible.

Getty image by Comstock.