How to Use Pain Scales to Explain Pain (Even Though They All Suck)

The fucking pain scale. If you’ve ever sought treatment for pain, you’ve heard this more than once.

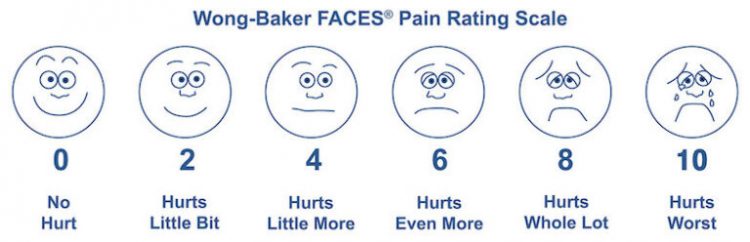

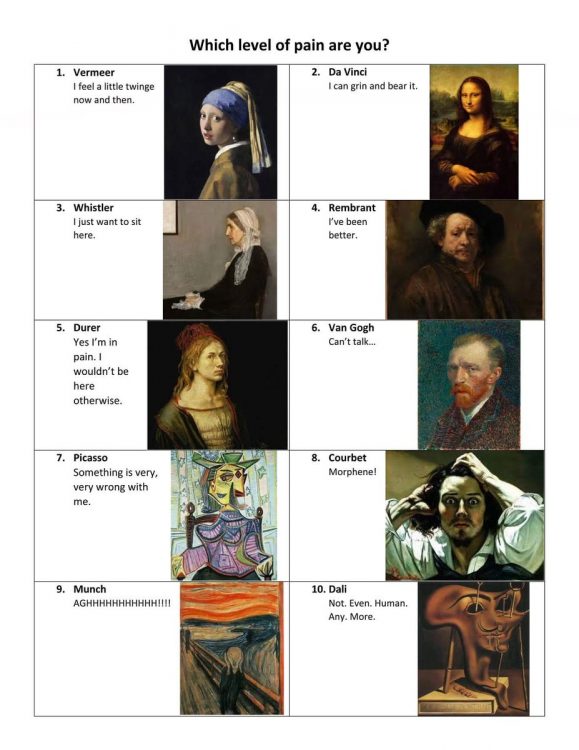

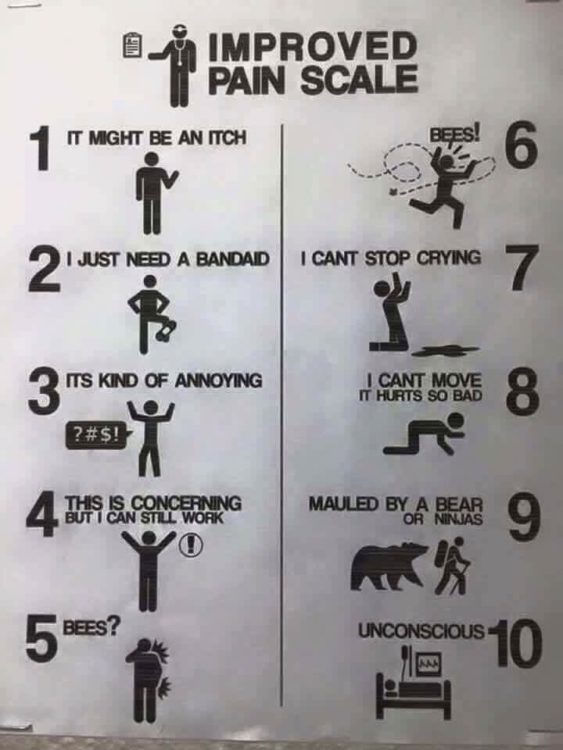

Ten means the worst pain you’ve ever experienced. Or else ten means the worst pain imaginable. Unless it means “bad enough to go to the ER.” Or just “very severe.” My new favorite is “Unspeakable / unimaginable. Bedridden and possibly delirious.” That seems closest to the gist of it. There’s even a visual scale for kids with faces!

The pain scale and its inescapable fuckery

All those things are completely different, of course. I mean… go look at that sentence again and think about how far apart some of those are. I’ve never given birth, had a kidney stone, or had my arm cut off without anesthesia, but I can imagine how badly those would hurt. If I truly went by “the worst pain you’ve ever felt,” my entire scale would have changed after my L5-S1 disc herniated. Does that mean that what was my 7 was now a 5 because the scale was stretched? “There are lots of problems that come with trying to measure pain,” Professor Stephen McMahon of the London Pain Consortium told The Independent in 2018. “I think the obsession with numbers is an oversimplification. Pain is not unidimensional. It doesn’t just come with scale […] it comes with other baggage. How threatening it is, how emotionally disturbing, how it affects your ability to concentrate.”

What does “the most pain you’ve ever been in” really mean?

I’ve been thinking a lot about this since I saw a post by someone new to chronic pain who said that they couldn’t understand the arbitrary value of a 1-10 scale of pain. She elaborated in a comment: “Especially when they say ‘10 being the most pain you’ve ever been in’ because yes the pain that I’m in all the time is the most pain I’ve ever been in but I always doubt that it’s a 10.” My response was: “Your instincts are right, you should lowball it. Don’t ever say 10, because they will dismiss you. If you’re not literally on your back screaming in pain, or flat-out unconscious, it’s not a 10. I say that not to be mean, but because I have been through this. Your normal everyday ‘worst pain’ is an 8. At MOST. That’s how you get a doctor to take you seriously.” And don’t ever, ever, ever say it’s an 11. Unless you’re Spinal Tap.

Turns Out Doctors Care About the Pain Scale Numbers, Not the Words

Here’s what drives me up a wall: the doctors who make us do this don’t know or care about the technicalities. A 10 is a 10 is a 10, I’ve discovered, no matter what the “definition” happens to be. Unfortunately, as someone who lives by words and who is very literal-minded in some ways, that realization took me faaaaaar too long.

The Pain Scale: Choosing the Best Version for You (Sorry, They All Suck)

Some people like to write their own pain scales, and there are a whole bunch of other all-slightly-different scales that do one thing or another. For instance, with the McGill Pain Index, created in 1975, doctors ask patients to select from among a list of sensory, affective, and evaluative descriptors for their pain, and assign a number describing their intensity. I’ve filled out this form so many damn times, even in my own medical journey over the last 20+ years (good lord, it’s really been that long, hasn’t it). But it’s still a subjective measurement that’s treated as objective and forced onto a numerical scale that truly doesn’t describe the situation.

Things I Wish I’d Known About the Pain Scale

I wish someone had told me at the start that my affect was being judged and noted every time I came in (“affect” in this case means the visible reaction a person displays toward events, often described by such terms as constricted, normal range, appropriate to context, flat, or shallow). I wish I’d known that the numbers on the scale matter more than the definitions that go along with them: even if a poorly-worded definition traps you at a 6, if your pain feels more like 7 out of 10, you should go with 7.

Describe Your Pain (Seriously, Actually Describe It)

But honestly, it’s better to just get done with the number and move on to the actual description. And that’s the right word, too: don’t just say your pain is bad. Describe how it’s bad. Describe the effect it has on your day-to-day activities. Describe the actual pain as best you can: not just “it hurts” but “it burns, it stabs, it clenches.”

My chronic pain started when I was 15. I wish, at the start, that I had the words to describe just how different my pain was at night than it was at 10 a.m. when I might have a doctor’s appointment. My affect at 10 a.m. and my affect at 10 p.m. are, well, like night and day. But just saying “it gets worse as the day goes on” doesn’t really communicate that. Turns out most pain gets worse as the day goes on, but not to the extent mine did, and it took time to figure out how to get that across.

Pain Scales: An Imperfect, Objective Measurement of a Variable, Subjective Experience

And that’s the crux of it: all these things are trying to objectively classify something that resists that categorization. There are so many types of pain, but even if you only have one (“only”), pain isn’t neat and tidy. So as you answer pain scale questions, keep the bigger picture in mind. Stress out less about the technical wording of the scale you’re using and more about how you’re going to get across the information you need to get across. Think of the pain scale as an intro to a conversation that might really be useful to both you and your doctor, rather than as the be-all-end-all. Or just scream “BEES!!!” and hope they get the joke.

This story originally appeared on JanetJay.com