Learning to Wear My Early Retirement as a Badge of Accomplishment

When you have lived your entire adult life with a serious, chronic illness, you learn to look at life differently than most other people. Ask the average person about their retirement plans and they will gladly tell you they would retire tomorrow if they could. So, when you tell someone you are retired and clearly not of retirement age, they automatically assume a response tinged with envy or jealousy that you were able to somehow achieve this amazing accomplishment.

What they often don’t understand is that, for those of us with serious, chronic illness, our “retirements” were not necessarily a welcomed event in our lives, nor did they come with the ability to choose our professional longevity or trajectory. Don’t get me wrong — I am not complaining, but illnesses such as ours take away so much of that illusion of control. So many of us worked so hard to keep our jobs and stay professionally viable that it comes as a stunning sense of shock and personal disappointment when we realize we just can’t fight fate any longer. I retired (early) at the age of 55, after working in my career for 32 years. Make no mistake — it was the right decision, given all of the ongoing medical issues I’ve had with my Crohn’s disease, peripheral neuropathy, Still’s disease and other ongoing autoimmune issues that my body battles every day and has done so for over four decades.

I was diagnosed with Crohn’s at the age of 18, so I know nothing different than living with Crohn’s as an adult. I fought to go to college, complete my degree, earn my master’s degree, then my doctorate and work in my professional field, all while balancing the disease processes and all it entailed. I worked hard not to be seen as “that” employee. You all know the one with Crohn’s disease, the one who takes more than the average number of sick days every year or seems to be in the bathroom so much more than anyone else. I balanced hiding in my job so that I didn’t stand out for my health issues, but somehow also standing out for my skills, abilities and talents. In doing so, I readily assumed the “I’m fine” mindset, even when I was obviously not well. I learned to downplay and under-react to my disease and what my body and health presented, which oftentimes left me sicker than necessary by the time I sought out support from my doctors.

I was the person who got so used to feeling terrible that it eventually became feeling “normal” for me, and I’d forget that I could even possibly feel better! So, after seven major surgeries in 16 years, I finally had to choose whether to return to work after an especially grueling surgery and challenging recovery, and after lengthy discussions with all my doctors (and I mean all: GP, rheumatologist, GI, hepatologist and oncologist) I made the decision that it was time to take care of me and my health. But, it was still the hardest decision of my life. For me, it meant I had to allow myself to admit it was OK and retiring wasn’t “giving in to the disease,” nor was it the end of my ability to be a productive and vital person. I learned to travel without feeling guilty. When someone asks me what I do for living and I say, “I am retired,” it almost always brings raised eyebrows and a moment of awkwardness. With invisible illnesses, our outward, physical presentations rarely match the severity of our ongoing, internal health issues. I still find myself feeling the need to add I retired early due to my medical issues, as though I owe them a justification.

Retiring for someone who is healthy and chooses their path in life is a celebratory experience. For those of us who have it thrust upon us without the proper time to acclimate to all it implies, it can trigger the sense that, “The disease has finally won.”

I had survived 32 years in a highly stressful and wonderful professional field and had earned the right to sit home and take care of myself, both physically and emotionally. But it took time for me to find ways to remain relevant and productive in my own life and in the community around me. I had to stop feeling strangely guilty when I told people I was retired and to learn to wear my retirement as the badge of accomplishment it actually was. I accomplished much in my profession as well as survived with multiple chronic diseases.

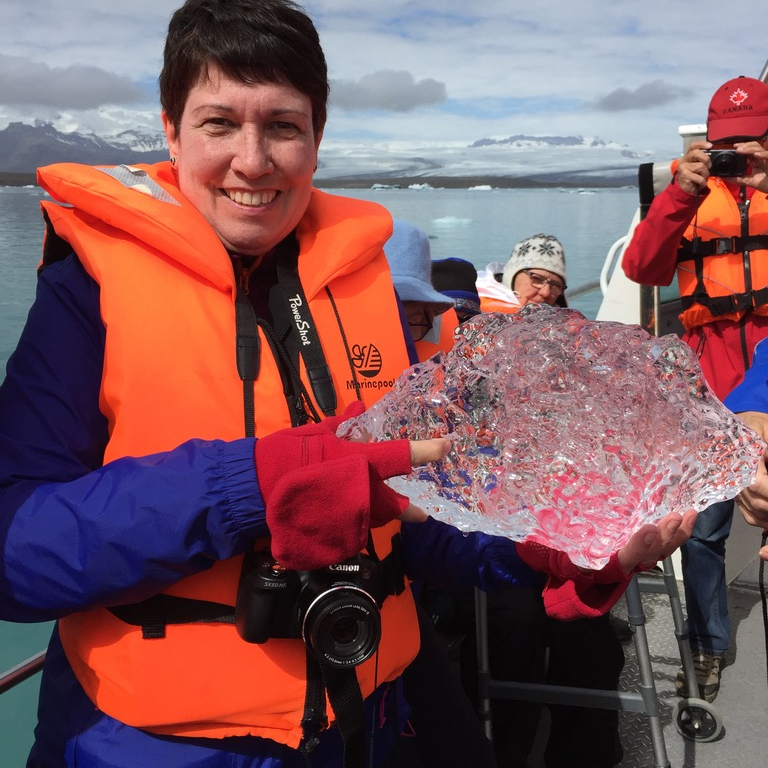

Lead Photo by rawpixel on Unsplash. Photo in article via contributor.