Why Disability Representation in Hollywood Is Not Just About Talent

Recently, there has been a lot of discussion in the media about disability representation in Hollywood, with everyone from disabled actors, to film lovers, to celebrities weighing in with their opinions and experiences. Non-disabled actors are being slammed for playing disabled characters. Film companies are being pressured to be more inclusive. Celebrities are leading campaigns to improve disability representation in Hollywood.

Some people argue that roles for disabled characters should only be offered to disabled people. Others argue that this would be equally discriminatory against non-disabled actors. Some believe it shouldn’t be an issue because “that’s why it’s called ‘acting.’” And some simply say the best actor should get the role, regardless of whether the actor or the character has a disability. But as with every social evolution, none of these arguments are that simple.

Let’s begin with a question: Why are there so few Hollywood celebrities with disabilities? If I asked you for the names of the disabled actors that have won an Oscar, could you tell me? It should be easy, since there were only two: Harold Russell for his role in “The Best Years of Our Lives” (1947), and Marlee Matlin for her role in “Children of a Lesser God” (1986). So, why only two? Are actors with disabilities just not as talented as non-disabled actors? Could it be because there aren’t many disabled actors in the first place? Or perhaps it’s because, historically, the film industry has not made a lot of room for people with disabilities.

Historically, classical Hollywood film mostly portrayed main characters who were Caucasian, straight, cisgender and non-disabled. Main characters who fell outside these parameters were usually caricatured and stereotyped according to societal biases. Most actors cast in leading roles were Caucasian, non-disabled and attractive by society’s standards. Actors who fell outside these parameters were relegated to the roles of villain, goofy sidekick, weirdo, servant etc. Although more than 20 percent of the US population has a disability, only about 2.5 percent of speaking roles in Hollywood films portray disability. Accurate representation of disability is rarely included in classical Hollywood film, and if it is, the character is often inconsequential to the plotline or framed as tragic and pitiable.

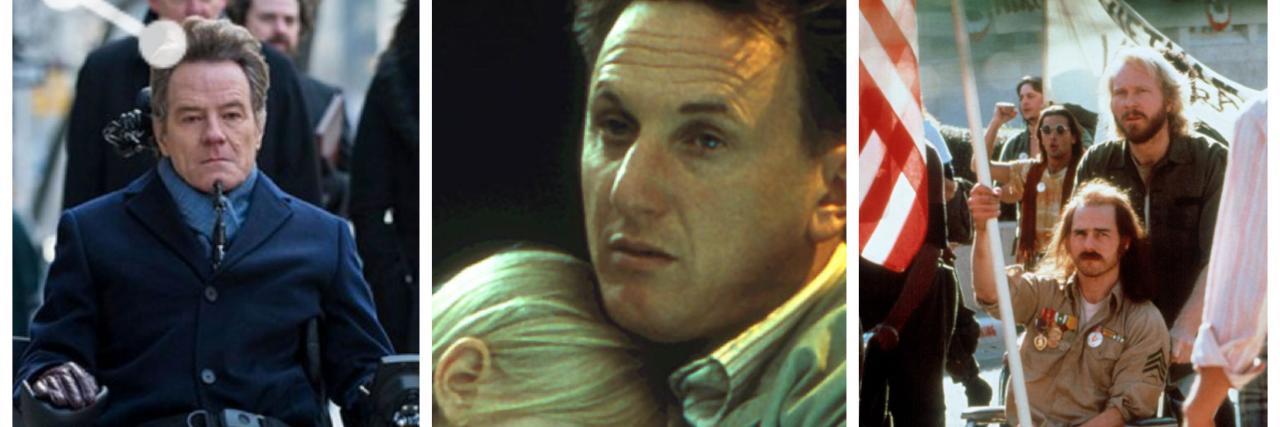

As disabled characters started to become more developed people with rich inner lives, motivations, and obstacles, these roles were given to non-disabled actors. In fact, 95 percent of all disabled characters are played by non-disabled actors. And playing a disabled character has proven to net great reward. Since Dustin Hoffman won an Oscar for his performance in “Rain Man,” Hollywood celebrities have been leaping at the opportunity to play a disabled character, and approximately half of the Best Actor Academy Awards have been received by non-disabled actors who played a disabled character.

Lack of opportunity is not the only barrier actors with disabilities face. Inclusion continues to be an area that is sorely lacking. Film producers often excuse themselves by saying “We couldn’t find a disabled actor to fill the role” or “Nobody with a disability auditioned for the role.” If casting directors don’t advertise a casting call, or invite disabled actors to audition, it’s not surprising that they don’t find a disabled actor to fill the role. There are thousands of disabled actors in Hollywood. Many of them are trained, and many are very talented. If casting directors cast a wider, more inclusive net, they would have no shortage of talented disabled actors to choose from.

Accessibility is another major barrier. Even if they are invited to audition for a role, disabled actors are often unable to do so, or to work in the film at all, because of lack of accessibility. Audition rooms, film studios and film sets are notoriously inaccessible for mobility device/aid users. Even the stage design for the Academy Awards has been woefully inadequate. In 1999, Dan Keplinger, an artist with cerebral palsy, won Best Short Subject Documentary for “King Gimp,” which he wrote and starred in. He was unable to accept the award because he could not reach the stage in his wheelchair.

Lastly, let’s talk about attitude. Historically, society’s attitude about people with disabilities has been one of pity, condescension, distaste, apathy and detachment. In society’s eyes, life with a disability is often regarded as tragic and horrifying, and stories about people overcoming their disability are inspirational and heart-warming. Audiences love disabled characters, but not disabled people, and Hollywood has only reinforced this attitude.

As you can see, disability representation in Hollywood is not just about an actor’s talent and ability. It is a systemic issue that has developed over the better part of a century, and will take time to change. In order to make that change, there needs to be a fundamental shift in attitude about disability, and a genuine effort to include actors with disabilities and provide the accessible space and resources for them to work safely and collaboratively. Hollywood needs to reach out to the disabled actors that have been reaching out to them for decades.

One of the great things about mainstream Hollywood film is that it is popular and far-reaching. It can reflect society’s values, and it can be a tremendous vehicle for change in society’s attitudes. The more Hollywood represents all people in society as having “normal” human struggles and emotions, the more society becomes accepting and respectful of differences. Disabled actors bring genuine life experience with them, and are able to play the character’s struggles and reactions with an authenticity one can only draw from actually living the experiences. They can provide valuable insight to help make the story richer and more believable. And they can bring skills and talents that have been hidden away or blocked from the big screen since the beginning of film.

With the tremendous increase in film budgets and advances in editing technology, there is no reason not to cast disabled actors more frequently. After all, in today’s age, it could be less costly and time-consuming to edit in Lt. Dan’s legs at the beginning of “Forrest Gump” instead of editing them out later in the film.

I have faith that in time, disability will be regularly and authentically represented in Hollywood film, and disabled actors will be appreciated and hired for their unique talents and experiences as much as non-disabled actors. Perhaps then, when barriers and biases are eliminated so disabled actors have equal opportunities, we will have the luxury of hiring actors based on talent alone. Although, by then, after having learned that lived experience is as valuable as talent, we may not want to!