Disabled Stanford Student Isn’t Alone in Her Battle for Home Care Services

Sometimes the news isn’t as straightforward as it’s made to seem. Karin Willison, The Mighty’s disability editor, explains what to keep in mind if you see this topic or similar stories in your newsfeed. This is The Mighty Takeaway.

A new school year is starting, and once again a promising young university student with a disability is in the news. At a time when she should be excited about choosing her first classes, moving into the dorm and making new friends, Sylvia Colt-Lacayo is worrying she won’t even be able to finish her freshman year at Stanford University.

Sylvia has muscular dystrophy and needs 18 hours per day of support from a personal care attendant to get out of bed, shower, dress, use the restroom and manage other daily tasks. However, the state of California’s In-Home Supportive Services (IHSS) program is only giving her less than half that amount of care, which would leave her unable to attend Stanford.

After a months-long battle, Sylvia eventually obtained 11.5 hours per day of care through another California program, WPCS, but she still had to set up a GoFundMe to raise money for additional support. And she will face this ongoing battle for the rest of her life. In an article written by Kaiser Health News and republished by The Mighty, Sylvia says, “This is a debt that will follow me forever.” Sadly, she’s right.

The Promise of Stanford

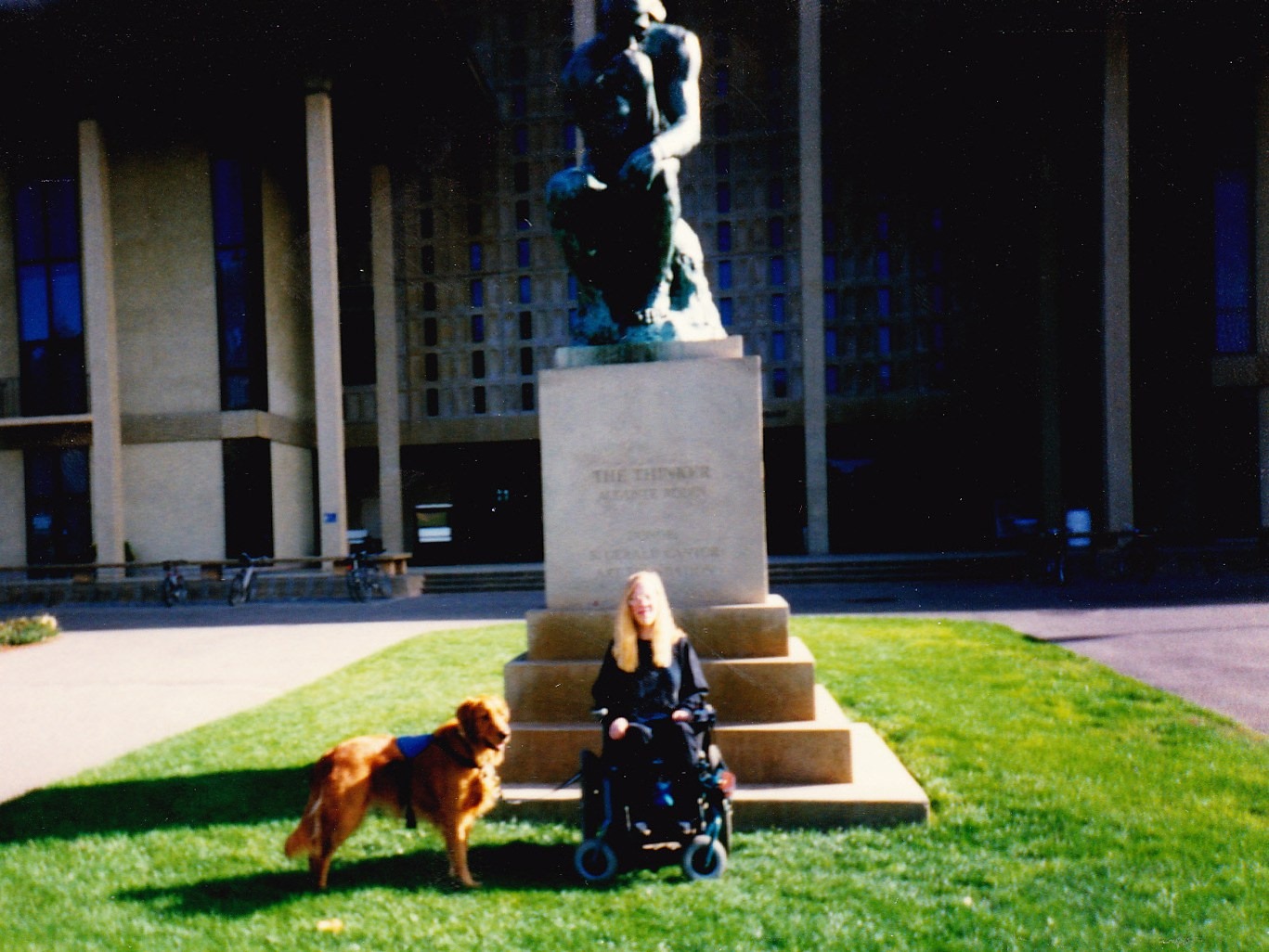

Sylvia’s story hits home for me. I am a Stanford University graduate with a physical disability and require personal care attendants to help me with most daily tasks, including dressing, bathing and using the restroom. Thankfully, when I was at Stanford I received financial support for paying my caregivers via Vocational Rehabilitation services in the state where I grew up. At the time, I didn’t know how fortunate I was to have that funding.

Stanford was like a utopia to me after growing up in small Midwestern cities. Diversity was celebrated there and I felt accepted as a person with a disability. I hired fellow students to assist me and was able to focus on my education and personal growth. I had an amazing experience at Stanford and I graduated feeling prepared to go out into the world and succeed.

The Debt That Follows You Forever

I moved to Los Angeles, where I worked for a couple of internet startups and later got my master’s degree. I was on my way to achieving the dreams my experience at Stanford taught me to believe were possible. But then I found myself with “the debt that will follow me forever,” and my life has been a struggle ever since.

After an abusive partner emotionally and financially exploited me, decimating the funds I had used to pay for caregivers after college, I had to apply for support through the California IHSS program. I was experienced at advocating for myself, so I knew to read all the online documentation I could find about IHSS, and got statements from my physician and a physical therapist stating I needed the IHSS maximum of 283 hours per month. I then created a document detailing every aspect of my day and how long each task I need assistance with takes to complete. With so much evidence, I felt confident I’d get the maximum IHSS hours.

That’s not what happened.

My first IHSS social worker seemed to already have a set number of hours in her mind when she arrived at my home to evaluate me. She was condescending towards me, outright said I wouldn’t get as many hours as I “wanted,” then made it evident that she would disregard my documentation, while also claiming to be impressed by it. When I received the results of my evaluation, I found she had given me only 180 hours of care per month.

I was shocked. I am visibly significantly disabled and need assistance with just about everything, and I had supplied more than enough proof to back up what common sense should have already made clear. The idea that I could survive with less than six hours per day of assistance is patently absurd. The idea that someone with no medical training could arbitrarily make such a judgment was even more absurd. I filed an appeal immediately.

A Brutal Appeals Process

Sylvia has not filed an appeal for more IHSS hours, but if she does, in my experience it is a grueling process. I’ve had several people share their appeal horror stories with me, but most didn’t want to discuss them publicly. So I will share mine.

I had to appear before an administrative law judge, with the IHSS social worker and a county representative on the other side arguing against me receiving additional hours of care. During the hearing, I was asked many deeply intrusive questions by the social worker and the judge, including how long I needed to spend on the toilet and how long my menstrual cycle lasts, even though I had included that information in my written documentation. When I answered, the social worker said she didn’t believe me and demanded more and more humiliating details about personal hygiene topics. At one point she started a protracted argument insisting emptying the trash took only three minutes, not the five minutes I had listed. Literally every minute of my existence was questioned and picked apart in excruciating detail.

I managed to stay calm and professional throughout, but as soon as I left the building, I burst into tears. I had provided them with more than enough evidence, yet I was treated like I must be lying or scamming. There was no respect for my dignity or awareness that so many of the questions were completely inappropriate. The whole process seemed designed to dehumanize me and make me beg for each minute of care I needed. I refused to do that — I fought for each minute instead, and I won.

A few weeks later, I received the judge’s decision in the mail. I had received nearly the maximum IHSS hours. But it was a hollow victory. I was emotionally scarred by the appeal hearing (to this day it remains one of the worst experiences of my life), I still didn’t have enough hours of care, and I now had to deal with the bureaucracy of the IHSS program.

Red Tape and Low Wages

I found myself still struggling financially, as I had to pay new caregivers out of pocket because it took months to get them enrolled as IHSS providers. I also had to supplement their wages as the county paid them less than they could earn even at local fast food restaurants.

I had one great main caregiver, but finding people for nights and weekends was a challenge. I started trying to hire workers who were already approved by IHSS, but I encountered mostly low-skilled applicants who could not handle my significant needs and active life.

Lack of Safeguards Leads to Abuse

Eventually, I was the victim of a violent attack after an already-approved IHSS provider I had let go for poor job performance sent her boyfriend to break into my home. He held me at gunpoint and threw me out of my wheelchair, but his plan was thwarted when my main caregiver managed to escape from him and run for help. The fired caregiver and her boyfriend later sent me death threats and I had to flee the state of California for my own safety.

I called my IHSS social worker to report that one of their registered caregivers had perpetrated this crime, but she did not return my call for over four months. By then, both the caregiver and her boyfriend had been arrested and charged with attacking me. They eventually received long prison sentences, but that does not undo the damage the IHSS program did to my life, nor did it lead to any changes to IHSS that might make it safer.

To my knowledge, IHSS still has no official process to report abusive caregivers and remove them from the program, and they allow individuals with serious felony convictions to work in the homes of vulnerable disabled and elderly people. In fact, after their release from prison, the individuals who attacked me could both work as IHSS providers immediately if the recipient they assist signs a waiver. Ten years after their release, they’ll be fully eligible to enroll, with those they care for not even notified that they committed a violent crime against an IHSS recipient.

This is the program one of California’s brightest young students must rely on as she pursues her education at one of the highest-ranked universities in the country. This is also the program many of California’s poorest, most medically fragile disabled and elderly people must rely on to survive each day. And it’s failing far too many of them.

Fighting for Support

I am a member of a few Facebook groups for people who receive services through IHSS, and asked if anyone had stories to share.

“Carol” (name changed to protect her privacy) has a 28-year-old daughter with autism and an intellectual disability. Her daughter has received IHSS services since 1997 and qualified for protective supervision hours because she can never be safely left alone. However, beginning in 2016 a new social worker began cutting her daughter’s hours, and removed her protective supervision hours in 2017.

Since then, Carol has appealed to reverse the cut multiple times without success; she stated that one judge, “told me… he didn’t want to hear ‘he said, she said,’ so we sat there for well over an hour saying nothing. [My daughter] was denied. I requested a rehearing which came 8 months later. I had a psychiatric evaluation done by our regional center. This judge was worse than the other one.” Carol is still fighting to have protective supervision hours reinstated for her daughter, but cannot afford an attorney.

“Laurie” (name changed), a disabled woman in San Diego County, has been searching for a weekend IHSS caregiver for over a year. When she contacts workers listed on the IHSS registry, she says most never even return her call. She further explains, “Most here don’t speak English so it’s hard to communicate. Most of these people, not all, can’t get a job elsewhere so that’s why they’re on the list. The one I have now comes on a bus and can’t even do my shopping etc. I have to take her which can be difficult when I am ill but she’s the best I can find… I live in a major city but no one wants to do this work. Not for $12.50 an hour. That’s minimum wage here. To compete IHSS needs to raise the rate to at least $17 an hour.”

A Nationwide Problem

To be fair, California is not the only state with a home care program that fails severely disabled people. Earlier this year, Anna Landre, a young woman with spinal muscular atrophy, nearly had to drop out of Georgetown University after New Jersey Medicaid wanted to reduce her hours of care from 16 per day to 10 per day. After considerable media attention and multiple appeal hearings, her care was reinstated and she was able to continue at Georgetown.

Getting Medicaid-funded home care often depends on where you live. Emmy award-winning filmmaker Jason DaSilva qualifies for 24-hour care in New York due to progressive multiple sclerosis, but after his son’s mother moved to Texas and he tried to relocate nearby, he discovered the state would only provide the amount of care he needed in a nursing home. His latest documentary, “When We Walk,” chronicles his heartbreaking dilemma: should he move and lose his independence, or stay in New York and miss out on precious time with his child as his disease continues to progress?

People with disabilities who need Medicaid personal care attendant services face these kinds of gut-wrenching “choices” every day. My boss offered me a raise; do I have to turn it down because making $2,000 per month will make me ineligible for the $4,000/mo in caregiver services I need? Should I divorce my spouse so they don’t have to go bankrupt before I can get Medicaid home care? Should I hire this poorly qualified applicant to assist me after struggling for months to find anyone willing to work for such low pay?

The Poverty Trap

People often ask me, “Can’t you get insurance to cover your care?” The answer is no — there are no private insurance companies that cover long-term in-home care, unless you bought long-term care insurance before becoming disabled. People with disabilities who need many hours of personal care attendant services have no choice but to apply for Medicaid and deliberately impoverish themselves or stay in poverty.

As a Stanford graduate, I might be considered more likely to get a high-paying job. Indeed, I count several doctors, lawyers and software developers among my Stanford alumni friends and classmates. But I don’t believe any of them would be able to easily afford the over $4,000 per month my care would cost without Medicaid — except for Marissa Mayer, former CEO of Yahoo, who lived in the same dorm as me. I’m not even jealous that I don’t have $620 million like she does — I’d just like to be able to use the bathroom without having to fight for it in front of a judge.

I want that for Sylvia too. I want Anna and Jason and Carol’s daughter and every other person with a disability to be able to get the care they need while going to school, working and living in the place they choose.

Fixing IHSS and Other Medicaid Home Care Programs

We can improve home care programs right now, with both small and larger changes in attitudes and policies.

Social workers in the IHSS program and others, stop under-assessing people you know need significant support to thrive. Be an ally to the clients you serve and fight for them instead of against them. If someone calls you to report they’ve been abused by an IHSS caregiver, take action immediately to protect them and other IHSS recipients from harm.

California legislators, expand IHSS to allow more hours of care for people who need them, and increase wages to make the job more appealing to honest, skilled workers. Stop allowing people with violent felony convictions to care for IHSS recipients, and make sure anyone who commits a crime against an IHSS recipient can never work as a caregiver again.

National legislators and policymakers, we need your help to pass the Disability Integration Act, which would ensure people with disabilities in every state have access to home and community-based services.

I’d like to see my Stanford classmates — and one day Sylvia’s — take on this issue and change the system so anyone with a severe disability can receive in-home care, regardless of income. Realistically, all of us who are not Marissa Mayer will never make enough money to support ourselves and pay for our care out of pocket. So why must we be stuck with programs that force us to be poor and treat us as subhuman?

Medicaid personal care attendant programs can be good. In Indiana where I live now, I receive 13.5 hours of services daily, more than twice what my IHSS social worker claimed I needed. My Indiana case worker is wonderfully supportive and advocates for me if I encounter problems. The pay is low so I still have to supplement, and I have to keep my income within a fairly low range, but overall it’s a far better program and my quality of life has improved tremendously.

So I say to my fellow Stanford alumni and others in a position to advocate for change, will you join me in speaking out? If you work in health care policy or for Medicaid, will you reach out to me and other advocates with disabilities to learn more about these problems and how to solve them? Millions of people with disabilities, including Stanford freshman Sylvia Colt-Lacayo, are counting on you.

More Information and Resources

- Medicaid Home Care Directory — a state-by-state list of consumer-directed personal care attendant programs

- Tips for Getting Medicaid Personal Care Attendant Services — how to win the fight and get the care you need

- In-Home Supportive Services Program (IHSS) — general information and how to apply

Lead photo by SPVVK / Getty Images.