How Frida Kahlo Made Chronic Pain and Disability Visible Through Art

“I paint self-portraits because I am so often alone, because I am the person I know best.” — Frida Kahlo

At the Frida Kahlo: Timeless exhibit that closed recently at College of DuPage’s McAninch Arts Center in Glen Ellyn, Illinois, what gripped me as much as her artwork, the 26 paintings on display, was how profoundly her life and art were shaped by disability. I knew from the biopic with Salma Hayek that she led a life of physical pain, but had no idea she was bedbound so often and so long that she created a lot of her great art there. They even placed a replica of her bed right in the exhibit!

At age 6, Kahlo contracted polio that left one leg shorter than the other. At 18, she survived a bus crash that killed several passengers. Kahlo was pierced by a metal handrail that fractured her pelvis and punctured her abdomen and uterus. Her spine was broken in three places, her right leg in 11, her collarbone was broken and her shoulder dislocated. That fateful moment dealt her a lifetime of agony, isolation, and miscarriages, but also tempered her artistic vision and strengthened her resolve to realize it no matter what.

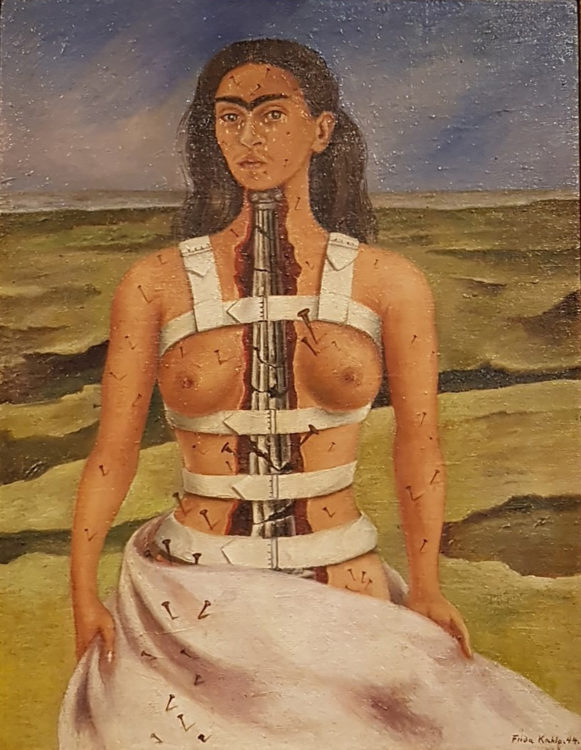

At times she saw herself and others in an almost disembodied way. She created surrealist paintings that looked like medical charts of her miscarriages, vehicular accidents, and the metal rods that propped up her back and caused chronic pain.

She turned that same almost clinical eye on her portrait subjects and on the way women are treated. One of the paintings shows the brutality a woman from the headlines had suffered at the hands of a murdering man, and Kahlo pulled no punches on the details, making sure viewers got to see how many women are treated. But on the other hand, her eye could capture the lace as fine as dewdrops on the sleeve of an otherwise poor and plain young girl whom she painted, signaling the beauty she saw inside of her young friend.

The exhibit highlighted the disability theme throughout the exhibit, and amplified the message by mounting a side gallery of works by Tres Fridas, a collective of artists Reveca Torres, Mariam Paré, and Tara Ahern. Tres Fridas (the name is a nod to Kahlo’s painting, Dos Fridas) stage disability-related recreations of famous paintings. The nameplates of their works show the original artworks to compare with, as well as explain issues that people with disabilities are dealing with today. Kudos to the McAninch Center for taking this opportunity to underline important issues that the general public gets little exposure to, and highlighting disabled artists.

Kahlo embraced her own disability as an intrinsic part of her whole self. She wore support braces around her torso, three of which were re-created for the exhibit. One was of burnished leather that resembled a hunting vest or leather armor. Another was molded plaster, decorated with exotic painted flowers and designs. Kahlo also had a leg amputated later in life and decorated her prosthetic.

Another way that disability was manifest in her art was in her subjects, especially herself. As a young woman (she died at 47), her energies and mind engaged with the wider world, yet for much of her life, her body would not let her. She and her famous and influential husband, the painter and muralist Diego Rivera, reveled in the company of artists and thinkers in Mexico and worldwide. One item in the exhibit is a short film showing her and Rivera with the historic revolutionary Leon Trotsky after he came to Mexico in exile from Russia. (Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin would send an assassin to kill him shortly afterward.) All this, and still Kahlo led much of her life in her bedroom, alone.

And yet, even forced to lie on her back, she created art. To create requires willpower even for someone able-bodied. That she continued to do so through pain and depression is a testament to her power as a person and artist. As I deal with similar issues, she amazes me.

Of course, Frida Kahlo is not only a disability artist. She was also a painter, provocateur, fashionista, and proud Mexicana (in the Mexican Revolution of 1910, Mexico threw off the yoke of dictatorship, and the society of Kahlo’s day embraced and celebrated its native culture and history). All of these things made up Frida Kahlo as a person and as a life, and she incorporated it all into her art and expression. Even her disability and isolation were not overlooked or kept hidden: they were turned into a source of power that made her work unique, that is, uniquely Frida Kahlo. Until recently, disability and depression were forbidden subjects. Now think about the taboos back in Kahlo’s time! Things like these seem like common sense, and yet we (me) sometimes have to learn basic truths like this, and it can take a great artist and museum to help us understand.

Viva Frida Kahlo!

Lead image via Wikimedia Commons. Other images provided by contributor.