The Bechdel Test for film and television has three criteria. To pass, there must be 1) two named female characters 2) who talk to each other 3) about something other than a man. The test “demonstrates how women’s complex and interesting lives are underrepresented or nonexistent in the film industry.” Like women, people with disabilities live complex and interesting lives yet are also marginalized in the film industry. Until now, however, there was no measure for gauging disability portrayal on screen. A simple test similar to the Bechdel test can help people decipher the disability messaging portrayed in a film.

In her book “Disability, Society and the Individual,” Julie Smart, Ph.D. writes that in film, disability is portrayed as “exaggerated” and “sensationalized” or used to “represent evil, anger, sin or internal aberration.” It is also commonly used as a plot device to elicit or heighten an emotional reaction. This is problematic for two reasons: first, even though most people can tell the difference between make-believe and reality, they don’t take the time to practice critical awareness about negative depictions of disability so all the negative messaging is internalized without them even realizing it. Second, widespread negative depictions of disability create and perpetuate an “us” and “them” mentality, effectively otherizing people with disabilities by situating them outside normalcy.

In truth, disability is both normal and common. So common, in fact, that in the U.S., people are more likely to have a disability than blue eyes. Only about 17 percent of people in the U.S. have blue eyes, while 25 percent of adults have “a disability that impacts major life activities.” Moreover, disability is the only minority group human beings move into and out of throughout their lives — sometimes multiple times — and is the only minority group a person will inevitably join if they grow old. Disability is a universal human experience and humankind would be better served if films normalized the experience rather than otherizing it.

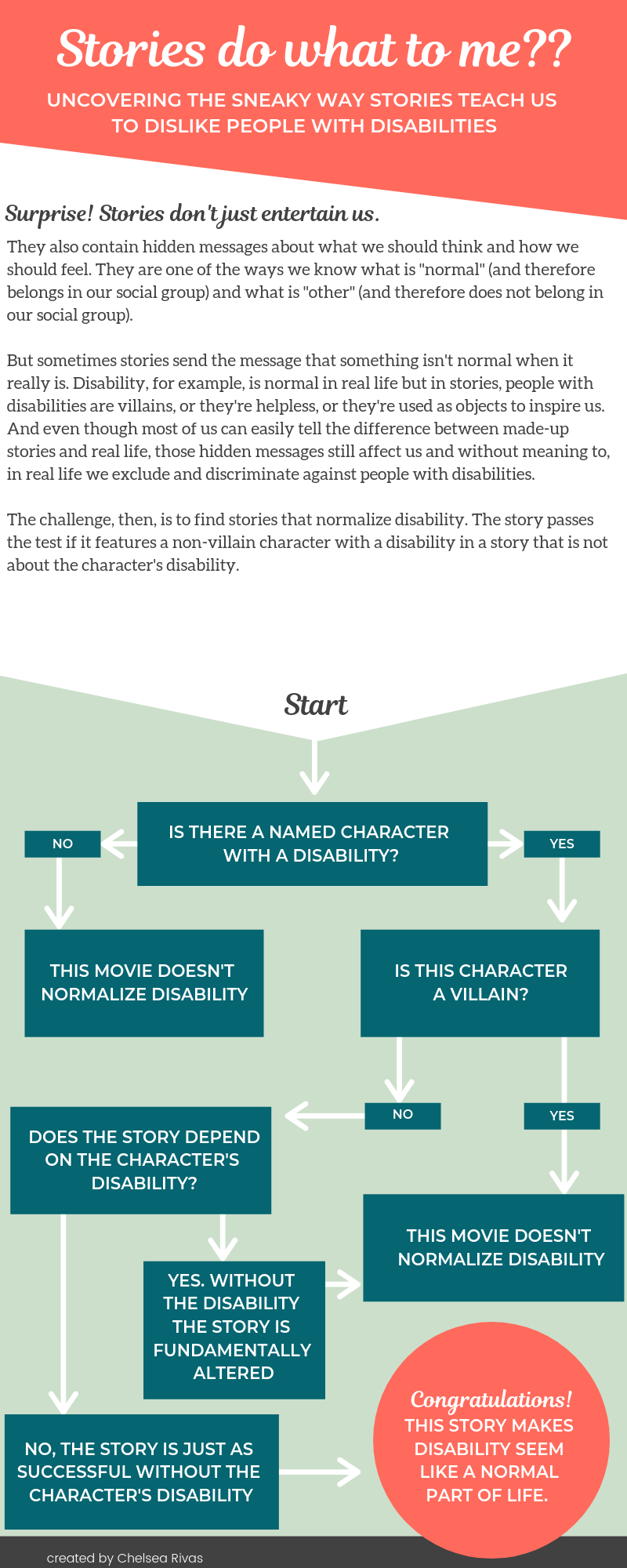

A film that normalizes disability should feature 1) A disabled character with a name 2) who isn’t a villain 3) and whose disability is not a critical plot point. If the plot depends on the character being disabled, it is often objectifying, otherizing or both. If the disability isn’t a critical plot point but the disabled character is a villain, then it too most likely falls into the “otherizing” category. However, if the disabled character isn’t a villain and the storyline would be just as successful without their disability, it’s probably a story that normalizes the experience of disability — which is the whole point. Storytelling is important. Stories convey important cultural information and people rely on story as a sense-making device.

The disability film test is an empowering tool, but it isn’t the solution in itself. The solution is better storytelling about disability. Ultimately, disability should appear as normal and common on screen as it is in real life. Storytellers and screenwriters shouldn’t be afraid to write stories that reflect the reality that disabled people are just like everyone else. And people shouldn’t be afraid to watch films with disabled protagonists. People need these stories. They need to see, hear and believe stories about disability until they assign as much social value to a person’s disability as they do to blue eyes: which is to say, none at all.

Getty image by Serg Velusceac.