Discrimination is shocking. Like a slap to the face — and I’ve only experienced it secondhand. Or maybe discrimination is too harsh a word. Maybe “misunderstanding” is the label I’m searching for in this context, but I don’t think so.

When it comes to my daughter Elyse, I have an overflowing jar of “meaning-wells” on my shelf, but somehow the more I receive, the less “well-meanings” I seem to have. With the sheer volume of superfluous good intentions, the point is lost, because good intentions and “meaning-wells” mean nothing when you’re drowning in them and when what you actually need is someone to listen and take you seriously. We are at risk of drowning in the well-meanings of others and losing Elyse at sea without careful vigilance.

It is often hard for parents who don’t have a child with Down syndrome to see, for anyone outside of individuals with Down syndrome and their family members to understand how people with Down syndrome are discriminated against on the basis of their diagnosis. Let me share a story to illustrate what I mean.

Around the time Elyse turned 3, was learning to walk, and we took the girls to Disneyland, Elyse learned the letters of the alphabet. Her speech was delayed, but she made sounds and enthusiastically yammered on, mostly nonsensically. Yet, she could say her letters. The year she turned 3, she attended an exceptional Montessori preschool that fostered life skills as well as academic pursuits. The school focused specifically on letters and letter sounds.

From the time Elyse was in the womb, we have read to her. In the NICU at the hospital, recovering from surgery as a newborn, we read to her. The nurses, too, would lean in for storytime. Sound has a way of curling around our insides like touch, and we aimed to heal our daughter’s wounds with our words. Books, comprised of letters and their sounds, were Elyse’s salve. At 3, we allowed Elyse to use the Sesame Street app that teaches letters on an iPad, which she was intensely interested in doing.

One day, when her grandma and grandad were over, Grandma pointed out that she thought Elyse was labeling her letters. I had an art easel out with letters printed on it, probably something I was doing to help Ariel, our eldest, who had yet to master the alphabet for lack of interest. “B, D, T,” Elyse said clearly, pointing to each letter correctly, one at a time, though she could barely speak. I was in shock! Elyse, 18 months younger, learned to label the letters of the alphabet before Ariel did. Keep in mind, Ariel, her older sister, is bright and inquisitive and receives excellent grades in school.

Fast forward now to junior kindergarten. Elyse is still 3 years old because her birthday is later in the year. I know how she looks to the outside observer with her pull-ups and small stature, but there is so much going on, so much that is not readily apparent because of her language delays. Then add in the fact that we send her to French school. Now she has to learn all of the letters again, in French. Admittedly, this takes her a while, but by the end of JK, she’s mostly there and into SK, surely she has solidified this knowledge she first latched onto so young.

Roll into grade one. Learning her letters shows up on her Individual Education Plan (IEP) as an expectation. I am adamant this be removed. Should Elyse choose not to demonstrate this knowledge, it’s because she is bored of it, not because she doesn’t know it. Her school is phenomenal. They listen to my concerns and we work together to get the expectations for Elyse’s learning where they need to be. Expectations are raised higher up, where they need to go. Once changed, the expectations remain realistic.

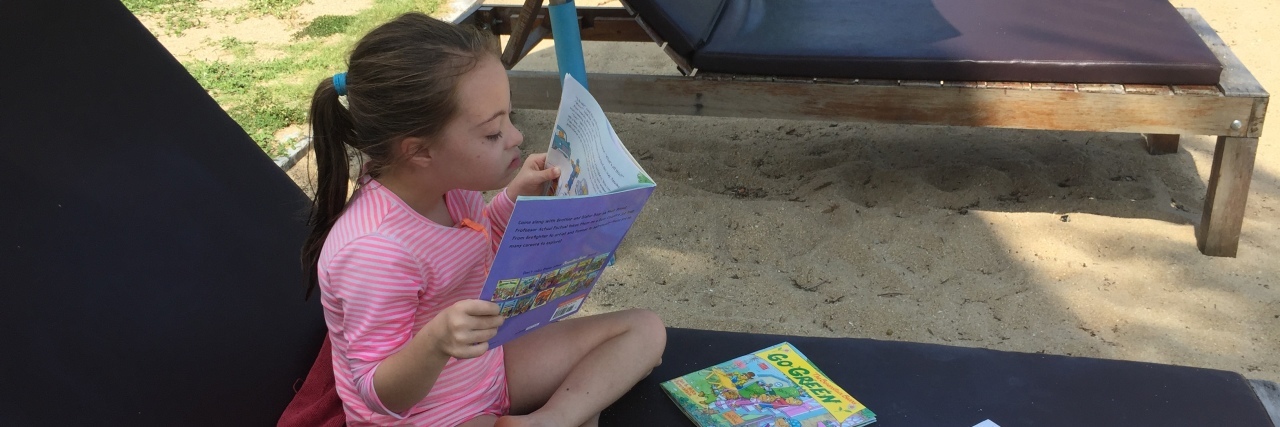

Enter grade two, the grade she is currently in. Letters are no longer on the school agenda, thankfully, but sounds are up there, as they should be. As you might have predicted (or maybe not?), Elyse is obsessed with books. She looks at books all day long in her spare time and we offer her an abundance in French and English. She has an intense interest in examining each page, but she isn’t quite able to decipher those words yet. She will likely learn to read holistically by decoding whole words by their shape, rather than how most kids are taught, which is using a phonetic approach, i.e. by sounding words out. Of course, there is great value in Elyse learning her sounds and the plan is that she will come to reading by blending the two strategies (holistic and phonetic). She can read certain repetitive short texts already, small sight words, it’s a matter of building on what she knows and where she is at. The same as for any child.

If we were really to take genetics into account when it comes to Elyse learning her letters, then we should probably look to her parents. I am a writer and a teacher who taught grade one students a second language and then taught those same students to read in that language. Now I help adult writers with their words. I read no less than 100 books a year, and you can damn well bet my kids are going to experience literacy to the fullest. In addition to a litany of scientific papers, my husband has one book to his name, in the form of a Ph.D. thesis. Our kids have two devoted parents, actively involved in their children’s lives. And don’t get me started on their incredible grandparents. Would you doubt our children would learn their letters?

But there are unfair barriers to Elyse’s success. Every new year is like a new beginning of convincing others what Elyse can do. We recently started a special reading program and the therapist outlined goals. On the third week of Elyse’s sessions, I arrived to find an alphabet chart out.

“What are you doing with that?” I asked cautiously.

“We’re working on her letters!” Oh no, you’re not. I quickly, calmly, explain Elyse is way past that. The therapist then hands me a paper with four attainable learning goals for Elyse laid out. These are the goals Elyse will be working on for the duration of the program. The second goal reads, “To recognize 10 letters.”

“No, absolutely not, not this one,” I pointed out immediately.

“You’re a woman who knows what she wants!” the therapist replied.

No, I’m a woman who knows what her daughter needs. This therapist means well, I know they do, and Elyse loves them. I believe that they care and that they are good at their job. I am so grateful for the work they do because our family benefits from the support. But thank goodness they were consulting me and open to my suggestions/demands. Elyse will not be subjected to “learning” her letters again.

The feeling I’m left with from the experience (and this is not the first nor will it be the last time) is that learning outcomes are too often being made based on assumptions, prejudices and discrimination — misunderstandings if you will. She has Down syndrome; she is Down syndrome, therefore she will only be able to do X, Y, and Z. No, no, no! These folks mean well, but no! I share this story not to shame; the problem is a societal issue.

It’s time to raise the bar. To presume competence, capability and intelligence. Elyse’s preschool teacher, a woman I know who really saw her, used to say to me all the time, “She’s a smart cookie!” And you know, she’s my kid, but I don’t care, I’ll say it anyway — she is a smart cookie and she deserves to be treated as such. She deserves the same respect other students do, the same chances at inquiry, the same push to succeed and grow, all of the best efforts to get her to learn. She does not deserve to relearn the alphabet. Every. Single. Year.

In Elyse’s place, wouldn’t you be bored? And how forgiving of misunderstandings would you be if it was your child?