In honor of Endometriosis Awareness Month and Women’s History Month, I’ve been reflecting on the experiences I had while seeking treatment for endometriosis. I learned the hard way that sexism is still common in the medical world: the myth of “female hysteria” remains pervasive, women’s pain is often dismissed, and to some doctors, the only thing that matters is a woman’s fertility.

It started at 14 years old with being told that vomiting, passing out, and writhing in pain for a week each month was considered “normal.” At 17, I learned that speaking up about my pain meant I was oversensitive or seeking attention, and the only possible diagnoses for any symptoms in a female teenager were pregnancy or depression.

By 19, I learned that severe, daily pelvic pain was to be dismissed by a doctor with a “suck it up and deal with it.” That a reaction of sadness upon finally receiving a chronic, life-altering diagnosis was to be patronized with a pat on the head and a “try not to look so miserable.” That being “sexually active” warranted shaming from a male doctor during a pelvic exam, and his suggestion to get pregnant is an actual “treatment plan.”

By 20, I understood that the perpetual violation of my body was to be done at my doctors’ will without any show of feelings from me, or I’d be chastised for being emotional and dramatic. I learned that sticking large needles into my uterus without medication or sedation is somehow an acceptable practice, and that being asked to be awake during surgery while they poked various places inside of my pelvis “to see my reaction” is the best they could do for trying to understand a woman’s pain.

At 21, when all treatment options had been exhausted, and each surgery, medication, and alternative therapy had failed, when a dozen doctors had given up on me and the years of horrific pain and neverending bleeding had rendered me bedridden, I learned that asking questions about a hysterectomy as a last-ditch attempt to regain some kind of a life signaled to the doctor that I was not in my right mind, and I needed to be sent to a psychoanalyst to assess the state of my mental health.

I was told that my fertility is important above all else, including my quality of life — even if I do not want to have children. I was told that I do not know what I want, but a male doctor, with whom I spent a sum total of 30 minutes, does. I learned that my only worth in this life comes from my ability to bear children; that my body is not my own, but belongs to a potential child I may or may not attempt to conceive in the future despite relentless pain and an inability to take care of even my most basic needs because my doctors could not, or would not, help me.

These experiences are not unique to me. A quick Google search reveals a plethora of articles, studies and statistics on how and why women’s health issues are dismissed, and the consequences that result. These statistics are typically even more grim for disabled women, BIPOC women and LGBTQ folks who, at the intersection of multiple marginalized identities, face compounding biases and additional obstacles in healthcare that must be navigated.

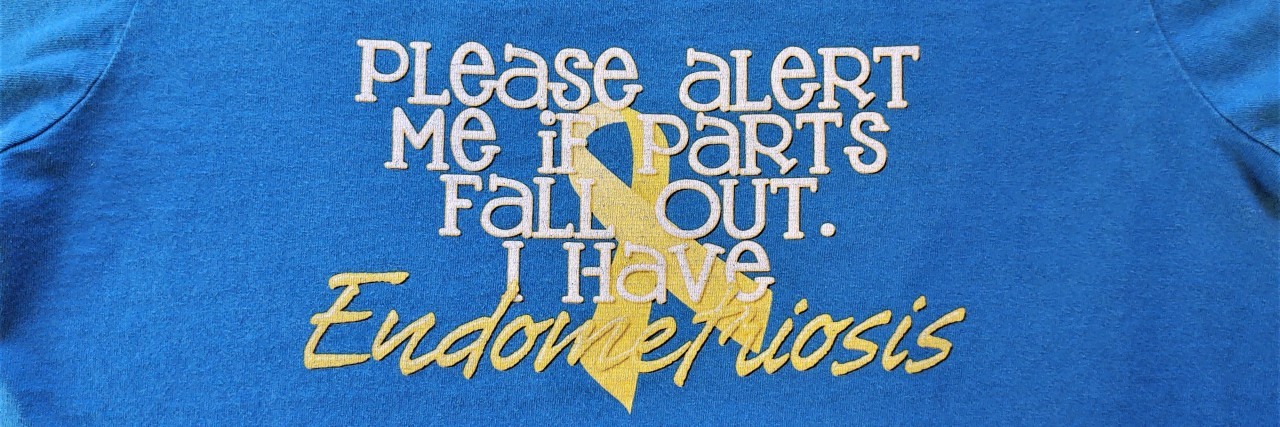

For endometriosis, studies have shown there is still a median diagnostic delay of eight years, citing the normalization of symptoms and the attitudes of health professionals as contributing factors. There is no known cure, and current treatments are not always effective. We still don’t know much about it, yet one in 10 women has endometriosis. Imagine how much agony and turmoil millions of people could be spared if women’s health issues were taken seriously — from how we are treated in the doctor’s office to receiving a prompt and accurate diagnosis to funding the research for efficacious treatments.

I don’t claim to know how to fix the myriad problems of the healthcare system, or the society in which it is situated. All I can do is offer ideas based on what I’ve done, or wish I had done, to make sure my voice was heard. We can start by advocating for ourselves. Keep notes about your symptoms, do your research, and write down questions before your appointments. Bring a friend or family member for backup and support. Be honest and firm with your doctor about what you need.

Remember: doctors are not the infallible heroes we see on TV. They are our consultants and partners in healthcare; we pay them for their expertise, not their judgment. If a doctor refuses to take your health concerns seriously and dismisses your pain, find another one. It may not be financially feasible for you to go from doctor to doctor, so you can narrow down the list of options by checking reviews for the doctors in your area, or read what they have to say on their websites. If you already have a diagnosis, join an online support group and ask for the names of the specialists they trust.

If you feel comfortable, take it a step further and share your experiences of dismissive doctors with others, both within those support groups and outside of them. Awareness is a predecessor of change; people can’t help fix what they do not know is an issue. This may look like posting on social media, writing reviews of doctors online, or filing a complaint if necessary. This can be difficult since you’re already struggling with your health, so don’t be afraid to ask for help from a trusted loved one, especially if the situation is serious enough to report the doctor.

We cannot change the entire medical system overnight, but we have to begin somewhere if we wish to claw our way out of this mess. Maybe someday, the medical community will listen and improve the education and training of new physicians, and established physicians will reflect on their own implicit biases. Maybe someday, research in women’s health issues will be more extensive and better funded, and diagnostic tools, clinical trials, and prescribing guidelines will improve. Maybe then, in this better world, an illness like endometriosis can be diagnosed quickly and treated effectively, or perhaps, since I’m dreaming big here, we will even find a cure.

As for me, I eventually found a doctor who listened to me, believed me and performed the surgery that gave me my life back. Within months I was pain-free and living a normal life. Ten years later, my endometriosis is still managed with one pill a day, and any occasional symptoms are mild. At 31, endometriosis is teaching me something new: I can use my voice and past experiences to raise awareness for these issues, so that maybe someday a 14-year-old girl won’t have to fight for eight years to get the medical care she needs and deserves.