The Diagnosis

“What do you think I am going to tell you?”

“Oh, I know I have it.”

“Well you’re right, you have Friedreich’s ataxia. That means probably by the time you reach high school, you won’t be able to walk very well and eventually you won’t be able to walk at all. Your life will be very different than that of your friends and family; most people with this disease have shortened lives. You may lose use of your hands and your speech may become very labored. You will have to re-imagine everything you thought for your life…“

Children’s Hospital of Michigan

April 14, 1998

I tune the doctor out at this point. I stare at a yellow school bus painted on the wall behind where he stands; it’s probably meant to preoccupy little ones while their parents are given life-changing news. I am 12 years old and I already know how life works. I’m not going to let some bully doctor tell me what I can do or how my life is going to turn out.

I am going to be an actress: singing, dancing, and acting are how I walk through my every day. It might be more of a challenge now, but I know it is an inevitability for me. This doctor is missing the most important part of this story: I have a living, breathing example of what someone with this disease can be: my big brother, Chris.

Chris had been diagnosed nearly 8 years ago, when he was 12. And now, at 20 years old, Chris is the coolest person I know. Yes, he had started using a wheelchair when he was in high school, but he didn’t let it slow him down. Music and art are his thing. He is always in Detroit at some concert with his local rockstar buddies. He wins awards for his drawings and designs, even though his hands give him trouble sometimes. All the doctor’s talk about having to give up your dreams or accept realities aren’t true for the one person I look up to more than anyone else, and they won’t be true for me.

The Talent

“To a girl I would be friends with, even if she wasn’t my sister.“

Love, your big brother, Chris

Wayne-Westland Junior Miss Program Booklet

November 15, 2003

After weeks of rehearsals, I’m not any more confident that I belong on this stage. I sit in my wheelchair next to cheerleaders, brainiacs, and dancers: all 22 are the most popular girls in my school. I had almost given up once, but now I don’t care that I won’t win, I want to be seen. I need to be seen.

We will be judged on Academics, Interview, Poise, Physical Fitness and Talent. The physical fitness routine is what almost made me quit. It is deemed that I have to complete the same six-minute routine as my competition. It’s certainly fair, and I won’t have it any other way than to have the same expected of me as everyone else. I just look ridiculous. I’m not putting myself down here; I legit have to do jumping jacks, push-ups, sit ups, and a couple high “kicks” from the comfort of my wheelchair. I force a smile on my face and pretend not to notice the absurdity of punching the air to the tune of “Walking on Sunshine.”

My talent’s a monologue I wrote about beauty. Beauty is in the “Eye of the Beholder;” pointing upwards, my voice breaks as I explain there is only one Beholder I recognize as my judge. Amidst talents of flashy dance numbers and gymnastic feats of flexibility, this monologue is my way of saying, “go ahead and judge me, because in the end, it doesn’t really matter.” I appreciate the irony; after all, I am voluntarily being judged in attempts to win a scholarship/beauty pageant.

There isn’t a dry eye in the house. The first thing I hear is my brother whooping loudly from the back of the auditorium, followed by the applause. The standing ovation is a surprise. As I wheel offstage, I am reminded why I love to be there; I earned this. The cheers and hollers are mine. The fact that I got it all for sharing the truth of who I am and what challenges me, makes it so much sweeter than I’ve ever known.

The rest of the program goes by fast: the onstage question, parading around in pretty dresses, and finally lining up on risers for the awards ceremony. First they announce the individual category winners. The two brainiacs win for Academics. The Physical Fitness awards go to a couple of the cheerleader/dancers, whose high kicks made the rest of us look like we were kicking off our shoes. The next awards are for onstage Poise, Interview, and finally, Talent. They call my name as a winner for Poise. I guess I carry myself well onstage: evidence of years of practice. Next they call my name as a winner for Interview. I wheel forward to collect another cash envelope and bundle of flowers. Now comes the Talent award. This is the one that really matters to me, the one that kept me in this competition when I wanted to give up. This is what I want to do in my life; this award could be validation that I still can, even though I do it differently.

“And the Talent award goes to… Emily S. for her jazz tap solo to “Yankee Doodle Dandy!” Of course it went to a dancer. Historically this competition awards dancers, singers, or those who play instruments. “Another talent award also goes to… Robin Bennett for her monologue “Eye of the Beholder!” I looked up from the flowers in my lap; did they just say my name? I am beyond honored. Yet this is not the feeling of validation I had expected. I feel the redness in my cheeks as I accept more flowers and see the crowd clapping happily once more.

That is my validation. Even when I was young, before my diagnosis, in Christmas plays and school productions, the reward of applause made me want to work harder and look past my challenges of standing up straight or moving as fast as my peers. Onstage, those limitations don’t hold as much power, because the stage is an even playing field where my abilities could outshine my disabilities.

I am back in my place at the foot of the risers; the 22 girls behind me are waiting for the final awards of runner ups and the Junior Miss title. I am content. I have done what I came to do. I was seen. Everything else is a bonus at this point. They call the four girls who are runners up. They line up in front of me with their bouquets and sashes. I can no longer see the audience. I look down at all the flowers and envelopes that I did not expect to win, and realize that I am holding the most flowers for winning individual categories. My heart begins to beat rapidly. My entire body feels numb. I can’t see, I can only hear as the announcer says, “And the 2004 Junior Miss Wayne Westland is… Number 12, Robin Bennett!“

The Challenge

“This is the last year that he and I share. Almost 8 years ago, my big brother, Chris, died from the disease he and I will always share. He was 26. I turn 26 tomorrow… On the brink of meeting him at the age he still stands at in my memory, where indeed he will always be, I am filled with fear… Fear – mixed with uncontrollable hope that I will surpass this even playing field we both are now on and become the “big” sister.

Broken Bird: A Collection of Writings

February 1, 2012

Chris passed away 10 months after my Junior Miss win. Entering the years after age 26, years that he was not given, I can’t help but take stock of where I’ve been and where I am. I graduated college with a Bachelor’s in creative writing and theatre arts. Since the initial shock of “What in the world am I going to do with this degree?” wore off, I’ve taken jobs that have allowed me to speak, write, and teach as an advocate for people with disabilities. I have not been on the stage since college and am intrigued when the therapeutic recreation program I work for announces they need a staff member for an inclusive theatre program called 4th Wall.

In the years since graduating college, I have been involved with independent living and direct services for individuals with intellectual disabilities. Having a disability, I have been so blessed to work alongside someone with a different type of disability so they can have fun, find their voice to advocate for themselves, or practice the skills that may not come easily for them. Now as I staff my first 4th Wall workshop, it all comes together: the joy of finding oneself in the communication, movement, and imagination of the theatre meeting the celebration of what is unique about every ability.

“You’re really good at this!” says one of the co-founders when class is over.

“Oh, thanks! I actually have a degree in theatre from Eastern Michigan University,” I reply, doing my best to seem humble.

“Really?” The other co-founder, overhearing us, walks up and exchanges a look with her counterpart.

The Passion

“This is what 4th Wall was founded upon: the idea that the magic of the theatre is something that should be shared with everyone, regardless of their different abilities (…) The true transformative magic of the theatre lies in self-discovery, in finding oneself and becoming comfortable in sharing with others what you’ve found.”

Annie Klark, 4th Wall Theatre Co. Co-Founder

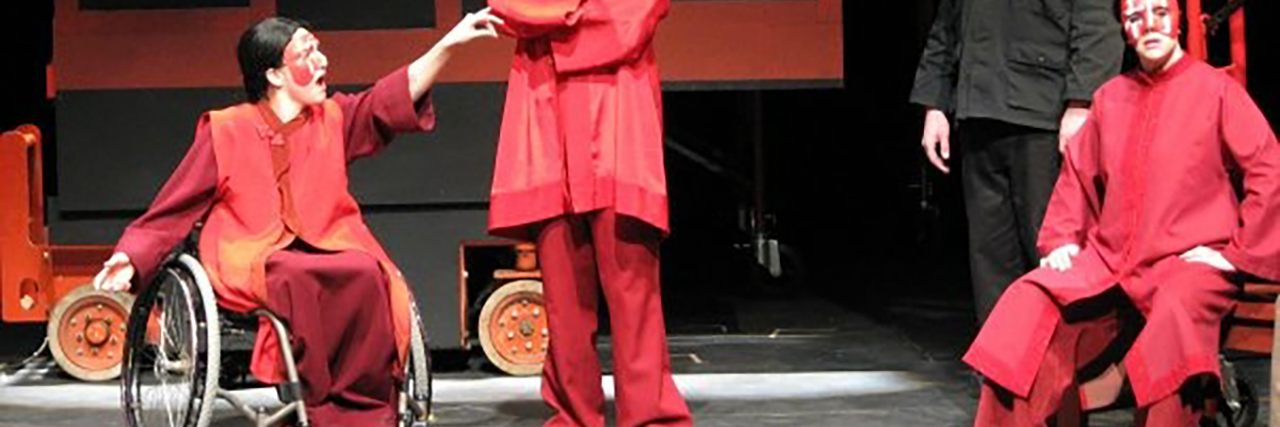

As of 2017, I have been an instructor and writer for 4th Wall Theatre Company for four years. The connection I have shared with students of all abilities has been strengthened by my limitations. Being an example of trying your best and keeping a good attitude, even if you have to do it differently, is my mission as an instructor and actor. For several years during my life, I thought I wouldn’t be able to label myself as an actor anymore. “My voice is too weak.” “My hands are too unstable.” “My strength is fading by the day.” Society, and sometimes even I, get too preoccupied with disability’s label.

Through this theatre company, I have taught children and young adults that society has labeled by their differences. Those who don’t speak. Those who don’t understand. Those who don’t fit typical expectations. But as I learned years ago from my lifelong hero and from my Junior Miss experience, disability fades away when you allow ability to take the spotlight.

A version of the story appeared on 4th Wall Kids.

We want to hear your story. Become a Mighty contributor here.

Photo by contributor.