Anxiety in very young children, or all children for that matter, is a pretty normal part of their development. They’re getting used to the world and making sense of their place in it. But for some kids, anxiety can have a more intrusive impact on their lives.

Explaining what anxiety is to older children and why it feels like it does will make a huge difference. They can do pretty amazing things with the right information. For younger ones, though, this can be a bit more difficult, particularly if their language is still developing. The good news is that there are plenty of things the grown-ups in their lives can do to help them through. The truth is there’s no one better.

1. Offer a comforting touch.

Humans were meant to be touched. It’s why we’re covered in skin and not spikes. If your little one is feeling anxious, touching them will initiate the release of neurochemicals that will start a relaxation response. Touching is one of the most healing things we humans can do. Try touching your child gently on the shoulder or the back — as long as he or she is OK with this, of course.

2. Or even better, hold them.

Even better than touching them is holding them. Anxiety feels flighty. It feels insecure and turbulent. Help your child feel grounded by holding them.

Research has found that hugging brings on a significant reduction in cortisol (the stress hormone). The huggable target doesn’t have to be human – just something huggable. (Though does it get much better than human?)

Let them feel you as a steadying presence. One of the symptoms of anxiety is clinginess. This isn’t surprising; actually, it’s another brilliant adaptive human trait. Young children might not be able to articulate it, but their body knows it needs to be grounded. If it’s what they need, give it. This won’t always be convenient, but if you can, let them fold into you. Stop cooking dinner, put down the phone and just for a couple of minutes, let them feel you keeping them safe. Make sure your own breath is steady so they don’t feel you as flighty. They’ll pick up whatever you send out.

Having said this, make sure after a quick cuddle, you also encourage a brave response. You don’t want to inadvertently reinforce their anxiety by giving them something positive (a cuddle) every time they become anxious. Cuddle them, then encourage them to try something that will ultimately move them toward learning an effective response, even if it’s just holding steady and breathing.

3. Use a soft toy pet to teach them about self-calming.

Make sure it’s an animal that’s fairly lifelike – a dog or a cat or something else that they would be happy to have against them. If you can get one that’s sleeping, all the better. At bedtime, tell them the puppy/cat/whatever has fallen asleep, too. Put it against their tummy or nestle it into the side of them and tell them they have to try to keep the toy pet asleep by breathing and moving very gently so as not to wake it up. This will focus them on their own body and develop their capacity to control their breathing – a valuable, relaxing skill.

4. Make sure their breathing is just right.

In the midst of anxiety, breathing changes from slow and deep to short and shallow. This is one of the reasons for the physical symptoms of anxiety in children, or anyone for that matter. Have your child practice breathing every day so that when he or she is in the midst of anxiety, it’ll be easier to call on effective breathing. Effective breathing comes from the belly, rather than the chest. Have your child practice their strong breathing by placing a soft toy on their tummy when they lie down. If the toy moves up and down, their breathing is perfect.

5. Use this specific kind of storytelling as a teaching tool.

We love stories because we can relate – to the characters, the feelings, the situation. As well as being good fun, stories can also be a powerful tool, particularly with kids. Let’s start with an example of a story and then we’ll talk about how you can use it. Make up a story about a child who has the same fear and shares other similarities with your child – maybe in relation to favorite foods, where they live, what they like.

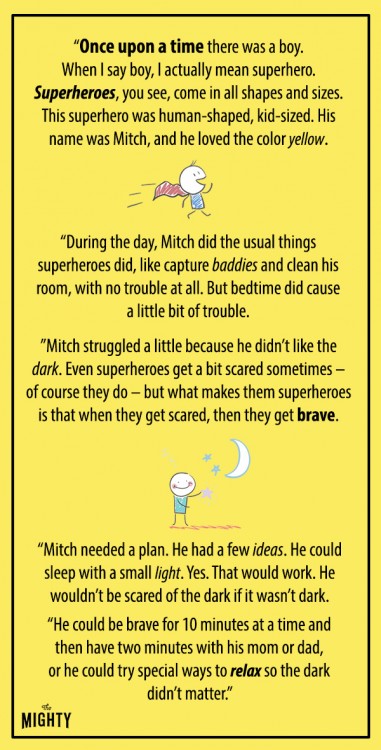

Here’s one idea to get you started. Add detail however you like:

This is just an example and as you can see, it doesn’t have to be a complicated story, just one they can relate to. A good story should do these things:

Help them understand more about the issue: Kids might find it easier to talk about feelings when they don’t have to own them directly. Stories facilitate this perfectly. Asking kids about the thoughts and feelings of a character can reveal a lot about where they’re at because their answers will be influenced by their own thoughts and feelings. For example, if you were telling the story above, ask your child: What does Mitch think might happen in the dark? What does Mitch need to feel better?

Involve them in the solution process: If kids feel as though they have some control and input, they’re more like to stick to the strategy you put in place. In your story, include the different strategies you might use to ease the bedtime ritual, and ask your child to choose. “So, if you were Mitch, what would you do? … You’re a bit of a superhero, I think this could work for you. Let’s try it.”

Help them find an anchor: An anchor is a word or phrase they can call on when they’re feeling anxious. Chances are, in the thick of an anxiety attack there will be no words, which is why it’s important to decide on the word or phrase beforehand and remind them of it when they need it. It might be as simple as “relax,” or “I’m OK.” Ask what would be a good thing for Mitch to hear when he gets scared.

6. Practice mindfulness with them.

If your child is worried, ask them where in their body they feel their worry might be living. Is it in their tummy? Their head? Arms? Legs? Chest? Ask them to gently put their hand on it, or they might prefer yours. Next, have them concentrate on their hand (or yours) and feel it comforting them. Remind them to breathe slowly in and out. As they breathe in, invite them to imagine the air going straight to their worry spot. Then imagine that when they breathe out, the breath is taking some of worry out with it. Just enough to make them feel more comfortable with the feeling. It doesn’t matter if it doesn’t go completely. The idea is to make it manageable.

7. Try the stepladder approach to anxiety-inducing situations.

The idea of the stepladder approach is to gradually expose kids to the feared situation or object so they can get used to it gradually. Start with a mild version of whatever it is that causes your child to feel anxious. Expose them a few times until they can handle it (make it super easy to start with), then move on to something a bit more anxiety-inducing. Expose them a few times until they get used to it. It’s important you don’t force them, but let them go at their own pace.

Here’s an example for someone who’s scared of dogs:

- Start with a book about dogs. Spend some time looking at the pictures.

- Move to a fluffy toy dog. Touch it and hold it with them.

- Look at dogs on television.

- Hold a friendly little dog and encourage them to look at it.

- Hold the little dog and encourage them to touch it.

- Let them hold the little dog.

- Encourage them to look at a big friendly dog.

- Encourage them to pat a big friendly dog.

8. Explain to your child there are better places for worries than keeping them inside.

Have them draw their worries, and when they feel done, invite them to rip up the paper and throw it away. Whatever you do, don’t forget to explain this is what you’ll be doing. You don’t want to be ripping up any precious masterpieces.

9. Create a source of comfort they can carry in their pockets.

This is a powerful technique for kids who struggle with separation anxiety. Copy a photo of you and a photo of your child onto a piece of paper. Make sure the photos are touching. Then cut the paper in half and fold it up – to keep it safe. Give them the photo of you and you take the photo of them. When they’re away, the photo of them stays in your pocket and the photo of you stays in theirs. At night, the photo comes back together and stays on the fridge or their mirror, or wherever it can be visible.

10. Don’t encourage avoidance.

The more your child avoids a situation, the harder it’ll be to face. Though you don’t want to push them too hard, don’t go out of your way to avoid the feared object. This could inadvertently reinforce the fear by communicating to them it’s scary and should be avoided. Praise any attempt they make to show brave behavior.

11. Avoid labels like “anxious” or “shy.”

It’ll become a part of their self-concept and they’ll behave in such a way as to reinforce the way you see them. Anxiety usually means that brave behavior is coming. Even if it doesn’t come straight away, generally they’re working on it. Focus on their attempt to be “brave,” rather than their “anxious” behavior.

For kids with anxiety, parents and the people who love them are so important and can really make a difference. Decide on the strategies that seem to fit for your child and stay with those strategies. Don’t worry if they don’t work the first time, or the first few. Anxiety can be robust and persistent, but with you behind them, your child can be even more so.

A version of this post originally appeared on Hey Sigmund.

Getty image by Catherine Falls Commercial