At age 20 I set out to complete a bachelor’s degree in industrial design. At the same time, I began experiencing mysterious physical symptoms, symptoms that would lead me to an unimaginable future.

I went from kicking soccer balls, running, and leading an active life to making use of leg braces and canes, and today, using a wheelchair full-time. After a tumultuous five years of searching for a name for this uninvited stumbling block, I would learn I had an extremely rare muscle deterioration genetic condition called hereditary inclusion body myopathies (HIBM), now referred to as GNEM, which could take my once active body to quadriplegic state. This rare condition affects 1,000 to 3,000 people worldwide. My condition is known to the medical world as an “orphan disease,” which is ironic, since I was born an orphan in South Korea.

All the doctors told me there was no hope. I was too rare to ever meet another patient like myself and I should quit college and lead a less ambitious life. According to their medical textbooks, my future looked bleak.

After completing my bachelor’s degree, I flew to California and found a design job as a toy designer. I also found two brothers who had my condition. One is a doctor, the other a research scientist. Together they set out to help propel advocacy and research science for HIBM. I was no longer alone and the medical world was wrong.

My world had opened, and I began advocacy to help spread awareness about my condition. I offered my design services and fundraised, but I soon realized it’s hard for people to empathize with medical textbook definitions, so I began blogging about my personal experiences with HIBM. I believe I was the first blogger with HIBM.

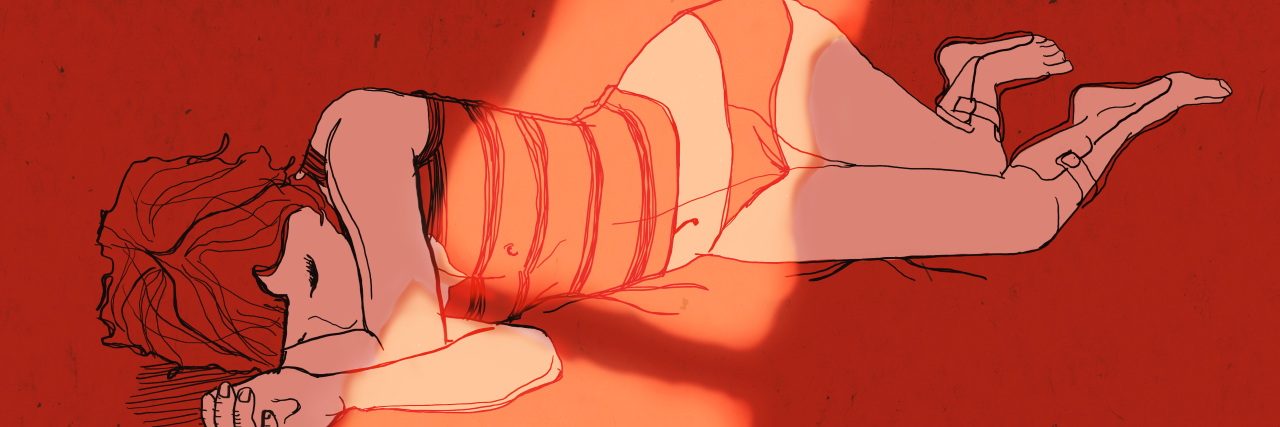

Then I realized some people respond to stories visually. So I taught myself illustration and began drawing out my experiences to raise awareness. I hoped my simple drawings would not only educate the viewer about HIBM, but also allow the viewer to see themselves in my drawings and relate it to their own struggles.

“Ultimately we know deeply that the other side of fear is freedom.” – Marilyn Ferguson

18 years later, I use a wheelchair, but live life even larger than when I was able-bodied. I’m constantly traveling and participating in daredevil stunts like skydiving, parasailing and scuba diving. I have a deep, unquenchable thirst for life and hold a philosophy of trying anything at least once.

HIBM came along when I was 20 and changed my whole world. Life felt both surreal and confusing. I was never one to fear death (except a painful one), but I never imagined becoming disabled—that was something that could happen to others but never to me, I thought.

When I went skydiving for the first time in 2011, my wheelchair had become a regular part of my life. I was using one during long-distance excursions and road trips, or even for getting around in shopping malls and art galleries. I had always been an avid traveler, but the reality of losing more and more muscle mass made my future a little murkier. As I sat there on the plane, about to jump out into the expanse below, I realized I had two choices: I could give up on the rest of my dreams by succumbing to fear, or face the challenge head on.

I chose the latter.

Life feels short, and nothing has made me more aware of that than my chronic condition. In a way, my condition has been a blessing, by forcing me to become more adventurous.

I tend to follow the lines of Twain’s “Write what you know.” And what you will find in my writing and art is an array of stories about my life that will hopefully resonate with many —the things that sometimes hurt us, challenge us, frighten us, make us laugh, make us brave or weak and make us cry.

While I am very public and comfortable with being and advocate for my rare condition, being an advocate and public about my condition makes me feel like this drawing most of the time.

I often hear “You’re an inspiration.” I get it. I say this to others too. But the truth is I don’t want to be an inspiration. Sometimes this comment makes me feel like a fraud — like I’m on a pedestal under false pretenses because I don’t want to be an inspiration. The “inspiration” just wants to be normal, preferably unknown.

My upper body has begun weakening and one day could be immobile, unable to draw. What do you do when you find out your future will be different than you thought?

You live, you draw.

Artwork by Kam Redlawsk