The Good and Bad of Involuntary Psychiatric Treatment, From an Involuntary Patient

In light of the recent Supreme Court Charter challenge to involuntary psychiatric treatment under British Columbia’s Mental Health Act, I was prompted to reflect on my own situation as an involuntary patient living in the community. This challenge has sparked a lot of debate, with one side strongly supporting the challenge, while the other states the challenge is “misguided.” In this piece, I’m not going to side with either argument; I’m simply going to present 10 facts and personal opinions about my experience as a person receiving involuntary treatment on extended leave from hospital.

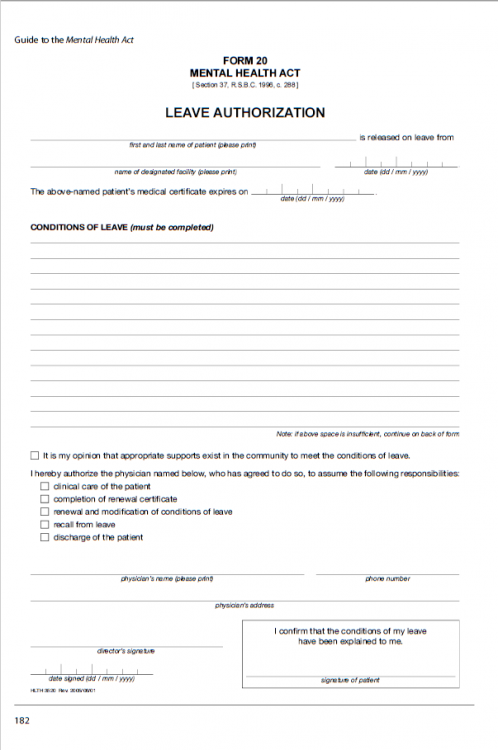

1. What is community committal or extended leave?

In B.C., community committal is a legal mechanism that allows for compulsory psychiatric treatment for a person without their consent. However, the person does not need to stay in hospital; they can stay in the community.

Extended leave is a type of community committal in B.C. that is usually used for patients who:

- have a diagnosed, severe and persistent mental illness

- lack insight due to the nature of their illness, and are unable to voluntarilyseek or comply with treatment; and

- need treatment in order to prevent deterioration that would predictably result in grave disability, or harms to self or others.

2. It can make you feel like you’re not in control.

When I was first put on extended leave, I wasn’t quite sure what it meant. It’s a scary term, being on “extended leave” from hospital. Will I need to report back to the hospital regularly? Does that mean I’m never going to be free from the mental health system? Do I have to eventually return to the hospital?

Then the conditions of my leave were explained to me:

- Attend appointments as scheduled by my mental health team, EPI.

- Comply with medications, including depot injection as prescribed by my treating mental health physician.

If I do not meet the conditions of my leave, I will be sent back to the hospital.

This, needless to say, made me feel like my autonomy and control was taken away from me. Who are they to tell me what I must do? I should be able to choose what to do with my life and my own body. I should have a say in who I’d like to see for follow-up, or if I’d like to follow up at all. But no, it has been decided for me what I am to do and the consequences.

3. It sucks to be forced to take medication.

Being forced to do anything isn’t fun, and when you’re mandated to take medication, that’s just plainly unpleasant. Being brought up in an all-natural, no-medication household, the idea of taking a synthetically-produced, chemical drug does not sit well with me. I don’t believe medication can help me much, besides lowering the intensity of my experiences that are labeled as psychosis, so, naturally, I hold strong reservations about medication. When I was told I am to report to EPI once a month to receive a long-acting, injectable antipsychotic, I was obviously not happy about it. Who wants to be subjected to a needle in the buttock once a month? Why not prescribe me oral medication? The only reason they set it up this way is to ensure I stay on medication, and to keep an eye on me. I find it dehumanizing and infuriating.

4. It feels oppressive.

I believe threatening hospitalization, forcing medication, and mandating treatment to a marginalized group is not only unfair, but also oppressive. Why don’t we have the right to refuse treatment, like those who receive general health care?

5. It makes hospitalizing you easier.

Another thing is it makes it easier for you to be given a bed in a psychiatric unit. Because you’re technically on leave and still certified as an involuntary patient of the hospital, when you need to go back to the hospital because of a flare-up or deterioration, you get first call on the first bed that becomes available.

6. But it shortens hospital stays.

Because your mental health team can “get you the help you need” faster and earlier, it reduces time spent in the hospital. They send you in, adjust medication and/or resources, stabilize, and send you back out. Ultimately, that shortens the overall hospital stay and gets you out faster.

7. And it decreases and prevents re-hospitalization.

Since I am required to have regular follow-up with my mental health team on extended leave, if anything is out of sorts, my team can hopefully catch it and deal with it before it gets worse. This can prevent a full-blown relapse, and therefore prevent re-hospitalization. Extended leave gives health care professionals the opportunity to handle things in the community rather than in the hospital, freeing up a hospital bed and saving lots of resources.

8. And it often helps reassure family and friends.

Having a loved one on extended leave often reassures family and friends because they know they’re loved one is getting the support and treatment they otherwise might refuse or not know they need.

9. And when you think about it, it doesn’t affect your day-to-day life that much.

Besides having to see my mental health team regularly and get an injection once a month, extended leave has minimal effects on my day-to-day life. I can go to school, volunteer, write, hang out with friends, go shopping, do fun things and not-so-fun things and basically live however I want. It’s more of the idea of being on extended leave that leaves a bitter taste in my mouth. At the end of the day, being on extended leave is a much less restrictive option than being stuck in a hospital, and I appreciate that.

10. But it still sucks…

Extended leave/community committal ignites heated discussion in the mental health community. While professionals and family members see it as life-saving legislation, a method to keep people stable and out of the hospital, avoiding a “revolving door” and providing reassurance to caregivers, friends and family — patients can often feel it is unfair and an infringement on individual rights, depriving them of their autonomy and leaving them feeling like they are less than human and have no control. That’s how I feel anyways.

Lead Image via Thinkstock.