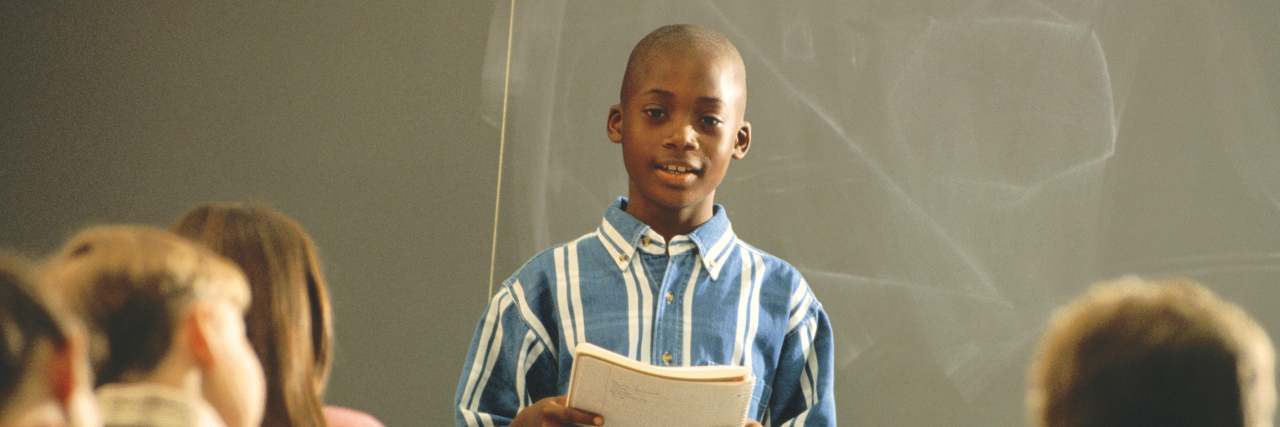

Why Making Anxious Students Do In-Class Presentations Isn't 'for Their Own Good'

I work in a high school in New York, and we are the first state to mandate mental health instruction, curriculum and awareness raising activities in grades K-12. I am the Outreach Specialist at my school and I have also been assigned to serve on our newly formed Equity Team, which has been created to offer support and resources to teachers in identifying signs and symptoms of mental health challenges with our students, and to also recognize that mental health is not always a negative thing. Indeed, all human beings have mental health.

The goal is to encourage knowing the difference between mental health wellness and when something has gone awry and a student may need help or support. We want teachers to know when the general sadness we all have from time to time may have slipped over to anxiety or depression that requires intervention, or a referral to a qualified mental health professional. We want to ensure no student falls through the cracks and all have equitable access to mental health care and support.

We have a number of students in our school that manage anxiety, ADHD or other mental health challenges and require and desire the same opportunities for educational success as everyone else. As a person who also stutters, I am acutely aware of the need for adults in a student’s life to be consistent, caring and meet students where they are at and with compassion.

I recently read a fascinating article on kids with anxiety who are self-advocating for the right to “opt out” of high pressure public speaking situations in the classroom. These kids often feel they are not ready to give a presentation in front of their peers, and that being forced to present may actually exasperate their anxiety. In my high school, our students are required to present often, as they should be; we need to be preparing kids for college and careers, where effective communication is a crucial life skill.

Many of our students are terrified of speaking in front of their class, and often ask for reasonable accommodations they are entitled to if they have a diagnosed disability and the accommodation is noted on their IEP (Individual Education Plan). Very often, our teachers will work with students in need of accommodations and have them present to just the teacher and one or two friends, rather than the whole class. The goal is always to have a hierarchical goal, where the next time the student will feel comfortable presenting in front of a few more people and eventually before the entire class. This approach demonstrates compassion for the students’ needs and also that we are “putting students first,” which is our school motto.

Recently I posted the article on Facebook, which invited comments from friends. Many commented that students should have not have “the right” to opt-out of mandatory school presentations. “It’s a rite of passage,” one said. “We’re raising a generation of wusses,” another said. I countered with agreement that we should be preparing students for life after school, and communication skills must be taught and honed so kids are ready for college and careers. But in the spirit of mental health wellness and compassion, we should not force kids who are telling adults they are not ready to do it anyway, “for their own good.” Very often, “for their own good” causes harm to kids with anxiety or who stutter.

I had a harrowing, humiliating experience in college. It was my third year and I was majoring in Social Work. We were told at the beginning of the semester that we would be required to do a 10 minute presentation in front of the class. I stuttered, and for most of my life, including college, I kept this hidden. I was deeply ashamed and afraid of laughing, teasing, mocking and judgment from peers and adults. I had been mocked about my stuttering a lot by other kids growing up — and once in a while by adults too. That also shocked me, that an adult would laugh at a child who stuttered. I know now as an adult that it probably wasn’t meant to be harmful or malicious, as they probably just didn’t understand stuttering, but it was indeed hurtful. So I protected myself, avoided speaking situations and hardly talked at all.

I agonized and obsessed for weeks over having to do this presentation, to the point I was making myself anxious and even a little physically sick. I finally gathered up my courage and asked my professor if there was some other way to present my knowledge of the subject, as I didn’t feel ready to stutter openly in a college setting. This was the first time I had acknowledged my stuttering and fears and actually asked for help. The professor denied my request, and said I must either make the presentation or take a zero for the class.

I felt backed into a corner. Of course I didn’t want to take a zero, as it would harm my grade. But I was worried that stuttering openly in class would harm me.

I went ahead and did it the presentation. It was the most humiliating and agonizing experience I’d ever had. I stuttered on almost every word, and felt myself physically tense up, struggle to breathe and my face and neck were flushed. Once or twice, I glanced up and saw my classmates stare at me with such pained expressions, as if they felt sorry for me. At least they didn’t laugh. When I glanced over at the professor, she had the same pained expression, but she also looked disgusted. I’ll never forget that.

When I finally finished, to my horror, I felt tears welling up in the sides of my eyes. I was afraid I would start crying, and desperately did not want to do that in front of the class. So I headed back to my seat, feeling quiet stares behind me and silent tension in the room. Instead of taking my seat, I walked out of the classroom and into a bathroom right next door. By then I was crying, as I was so embarrassed. I also felt myself begin to hyperventilate, so I went into a stall and before I knew it, I was having a full-blown panic attack.

I grabbed one of the brown paper bags provided for sanitary napkin disposal, and began breathing into the bag in an attempt to calm myself down. Mind you, I was just one room away from my classroom. I had been gone from class for well over 15 minutes by the time I finally started calming down and had stopped crying. No one came to check on me. How could that be? How could a 20-year-old college student walk out of a classroom in obvious distress, and no one was concerned enough to find me and see if I was all right?

I will never forget that experience. It most certainly did not feel “in my best interest” or “for my own good.” How can humiliation of a student of any age be appropriate? Especially when that student specifically reached out and asked for help?

We should be teaching kids who struggle with anxiety disorders, other mental health conditions or who may stutter that they need to challenge themselves and develop crucial communication skills. But we should also encourage and teach these kids how to self-advocate, talk about their disability and not be afraid to ask for help. And when that student does ask for help, meet that request with compassion and help the student feel proud that they spoke up. Then figure out together what might work best for them.

After that humiliating college presentation experience, I took a “deeper dive” into trying to hide my stuttering. That came at a huge emotional price. I always felt like an impostor, and felt trapped by not feeling allowed to just be my true self. It took me 20 years and lots of “aha” moments along the way to “recover” from that “for my own good”experience.

Most people in the education field — teachers, counselors, support staff — are not doctors. But it may be helpful to adopt the stance of doctors everywhere — “first, do no harm” — when it comes to pushing kids too hard when they may not be ready.

Getty image by Comstock.