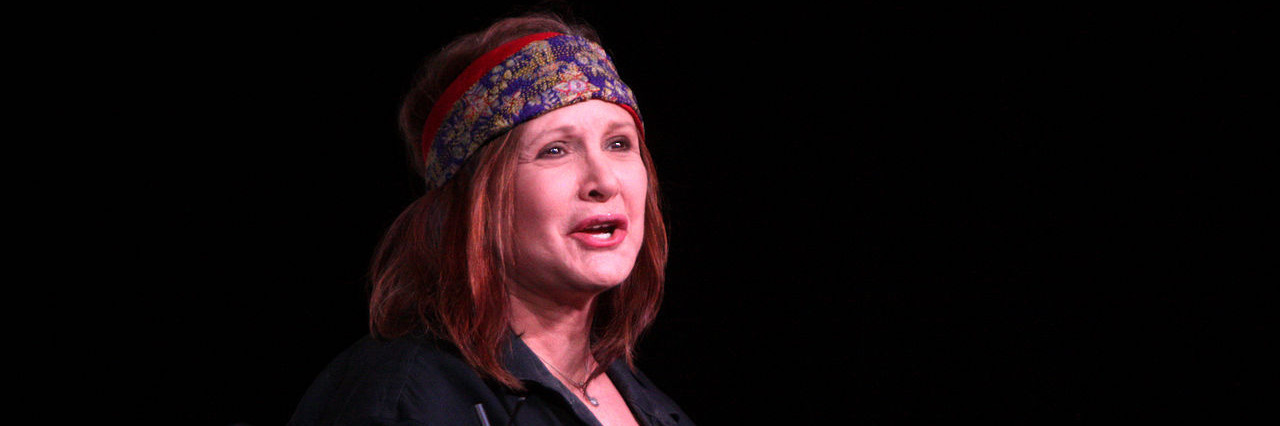

Carrie Fisher Showed Us How to Normalize Mental Illness Without Minimizing It

The previous night, it took me two hours to get ready for bed. I had to stand at my window on tiptoes opening and shutting the curtain until it felt “right.” I needed to wash my hands until my fingertips puckered. I knew I would have to get in and out of bed five, six, seven times before I could finally settle. For a while, I just stood beside the bed, exhausted and procrastinating the inevitable.

At work in the morning, I sipped my oversized coffee, dragging because I had gotten to bed so late. I watched a coworker fuss over a pile of papers she was organizing. Finally, she gave up, laughed and said, “Oh my god, I’m so OCD about this,” as she tossed a file folder into a drawer, shut it crisply and walked away. I envied her ability to discard an object like that, without being compelled to open and shut the drawer countless times, without anxiety crowding her chest.

I hate that my illness has become colloquialized, the punchline of someone else’s self-deprecating joke. I wanted to shout after her, “No, you don’t have OCD!” I wanted to explain that obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) patients don’t simply “care too much” about details, organization or cleanliness, as the stereotype dictates. I wanted to tell her that for many of us, this interpretation is flat wrong.

I’m the messiest person I know, and when I compulsively wash my hands, it’s not because I’m worried about whether they’re clean. I wanted to make her understand how much it hurts, sometimes physically, when I can’t stop a repetitive behavior. Yet, I said nothing because I was afraid of what she would think of me if she knew the truth.

Granted, the conversation surrounding mental illness has improved since I was diagnosed with OCD at age 11. At that time, the only model I had was Jack Nicholson’s character in the 1997 film “As Good As It Gets,” who is so emotionally numbed by his disease that it’s a near-miracle anyone could love him. In certain communities, a growing number of people attempt to understand the effect that language and representation have on people with mental illness.

In part, this is thanks to public figures like Carrie Fisher, who are open about their struggles. In the days after Fisher’s death, it was comforting for me to see fans mourned both her contributions to cinema and her role as an inspiration for people with mental illness.

Yet, even in these progressive circles, I am troubled by a growing trend in the way we talk about mental health. As it becomes more discussed and therefore more “mainstreamed,” most people rightly check their prior assumptions that mental illness is a sign of weakness or an indication that a person won’t live a full life. However, I often see people integrate their growing awareness of mental illness into their worldview by minimizing the struggle of people who live with it.

Many assume the only reason they know people with mental illness is that those people don’t really struggle with it and that they don’t really have a mental illness. It’s a trade-off: To see mental illness without the stigma, they minimize it. Stereotype is the language of this minimization as it enables someone to make light of a friend’s illness without realizing they are making light of it. This is exactly what happened when my coworker turned my illness into a punchline. If she had stopped to consider that OCD really is a struggle for some people or that those people can still be high-functioning (and therefore in her workplace, listening to her speak), she would not have colloquialized it as she did.

In addition to my coworker’s comment, I see this process of minimization when I attempt to describe for a friend what it is like to have immobilizing anxiety, and she brushes it off by saying, “Well, everyone experiences that sometimes.” I see it when I try to explain why I’m lingering in the doorway, taking my coat on and off, and someone laughs and says, “Oh, I’m a little OCD too.” I see it when, in order for my admission of mental illness to not be seen as a joke, I need to tell someone, “I have OCD. No, actual, clinical OCD.”

These situations tell me that, in the eyes of my peers, OCD is “mental illness light,” and my struggle is somehow negligible. Even if my friends and colleagues do not actually hold this view about OCD, the fact that I am made to feel this way indicates something is seriously wrong in the way we talk about it.

This perception that a mental illness is either “really bad” or something mild to be made light of maintains the problematic, old-fashioned notion of mental illness: That if someone really has a mental illness, they must not be high-functioning. It also makes it nearly impossible for those of us who are high-functioning to get the emotional support we need from friends and loved ones. For most of my life, I have been too afraid of the lingering stigma of mental illness to talk about my own for the fear of losing a respect I have worked hard to earn.

Yet, since Carrie Fisher’s death, I have been thinking a lot about what it means to “come out” as a person with mental illness. Her frank narratives of living with bipolar disorder not only uplifted other individuals with bipolar disorder but they also demonstrated how anyone with a mental illness can be honest about their struggle while still demanding the respect they are due.

Thus, the way Fisher spoke about her bipolar disorder is one possible model for acknowledging mental illness in a way that does not minimize or misrepresent the struggle of people who deal with it. In her 2008 memoir, “Wishful Drinking,” she addresses the stigma of mental illness head-on:

“One of the things that baffles me (and there are quite a few) is how there can be so much lingering stigma with regards to mental illness … In my opinion, living with manic depression takes a tremendous amount of balls… At times, being bipolar can be an all-consuming challenge, requiring a lot of stamina and even more courage, so if you’re living with this illness and functioning at all, it’s something to be proud of, not ashamed of.”

Here, she acknowledges the seriousness of her mental illness, but instead of allowing that seriousness to be something that marginalizes her, it becomes the reason she deserves respect. This is key to the way we should be talking about mental illness: A person is not strong despite their mental illness, but they are strong because of it. It is not a weakness, but an obstacle. If a person is attempting to overcome that obstacle, then no matter their degree of success, they deserve the utmost respect of the people in their lives.

Watching the reactions to Fisher’s death, I have realized that talking about mental illness (that is, talking about it in a way that acknowledges, not minimizes and uplifts, not condemns) often begins with people with mental illness talking about themselves. Despite my instinct to hide, I see the benefits of “coming out” as someone with a mental illness on both the speaker and the listener. I use the term “come out” because, as it recalls the complexities of coming out as LGBT, the term encapsulates the great risk and the great potential reward of presenting one’s full self to the world.

For the speaker, it is an act of catharsis. When Fisher wrote, in detail, about her experiences with bipolar disorder, I imagine she did so not only to inspire her readers, but also for herself. There is power in refusing to hide pieces of yourself, as it puts you in control over the narrative of your life and therefore, over the way others see you.

This honesty is also a relief. OCD spans the full terrain of my day-to-day, and so hiding it feels both necessary and unnatural (not to mention exhausting). I’m a master of excuses for why I’m, say, adjusting my position in a chair over and over. In addition to the energy already consumed by my obsessive-compulsive behaviors, the explanations I must manufacture for them take yet another layer of focus away from my life.

I have a fantasy about what it would be like to stop making these excuses. In it, I’m having a particularly difficult day, and it takes me a couple of tries to sit in my chair. When my coworker asks if I’m OK, I say, “I have obsessive-compulsive disorder, and I need a moment,” without having to worry whether she will lose respect for me. She gives me the moment I asked for, assumes I’m being serious and knows I’m no less competent at my job for having to struggle in this particular way. We move on from the whole thing pretty quickly, but the moment contributes innumerably to my energy and sense of self-worth. I can proceed without feeling ashamed, insecure or drained by the effort of fabricating a narrative to cover my mental illness.

In this fantasy, me coming out is a moment of growth for my listener. She realizes someone she already knows and respects has a mental illness, and thus, she sees that a person can have a mental illness and be high-functioning. She sees me as honest and brave. Sometimes, this fantasy even includes a young person listening from the corner, whose shame about her own mental illness and attempts to hide it only compound her anxiety. Watching me come out helps her see the world need not be stacked against her any more than it already is.

Inspired by Fisher, I have lately tried to enact versions of this fantasy, and I have realized that versions of it, messy, sometimes awkward, but mostly satisfying versions, can happen. When I have “come out,” many of my peers have listened and proceeded to treat me with the same respect as before. These interactions are rarely as brief or as idealized as in my fantasy. People often have questions. Sometimes, there are uncomfortable silences, but that’s part of the process of learning. I am learning how to be “out” about my condition, and they are learning how to coexist with people who are no longer hiding their mental illnesses.

A big part of the learning process is setting boundaries. Once, I bristled when someone close to me asked what I talk about in therapy. She defended herself by saying if I had a broken leg, it would be normal for her to ask about my recovery. However, I don’t have a broken leg. I have a mental illness. I reserved the right not to answer her because my mental illness is rooted in deeply uncomfortable feelings that I simply can’t share with anyone other than my therapist, and that’s fine.

I am not calling for people to share their deepest, darkest secrets with everyone they know. I also believe it’s wrong for people to ask probing questions about our mental illnesses. The point is I should be able to talk about it when and how I want to without losing the respect of my peers. Being afforded that right often begins with me talking about it more and setting boundaries for my listeners, so they can react more appropriately the next time someone in their life opens up about a mental illness.

It is certainly no one’s responsibility to “educate” others about mental illness by coming out. For most of my life, I would have balked at the idea of telling a coworker about my OCD, and I had every right to keep it under wraps. However, I do believe the problematic conversations around mental illness cannot be fully reshaped without the open participation of those of us who have them. Ideally, our peers would catch on to respectful ways to talk about mental health without us having to explain it. Yet, in the end, no matter how much our minds are studied, only we know what it really means to live in our heads, not to mention that there is empowerment in being forthright about those experiences. With the loss of Carrie Fisher, one of our greatest champions, our voices have quite a void to fill.

We want to hear your story. Become a Mighty contributor here.

Image via Wikiemedia.