For 250,000 disabled U.K. residents, going to the toilet is a military operation. Only you never hear about it. Why? Because talking about going to the toilet isn’t exactly fun. Sure we joke about those type of Facebookers who write a status about every single move they make — including going to the loo! For the majority, going to the toilet is a private, dignified human need that is straightforward and requires no second thought. Only those 250K I just mentioned are living a very different existence, merely because going out of the house means they’re venturing away from the only accessible toilet that meets their needs.

I am one of those 250,000 and for 14 years I’ve been too stubborn and proud to stand up (no pun intended) and say surely I should be able to go out freely and not have to worry about the next time I need the loo, on top of all the access issues I and every other wheelchair user faces on a daily basis!

So what exactly is the problem? Let me explain…

It’s wonderful that you will find a “disabled toilet” in nearly every public place. It is. They consist of a toilet with grab rails, and sometimes space to park a wheelchair, but nothing else. This means if you are unable to self-transfer (physically stand or shuffle from your wheelchair to the toilet) then these toilets are not accessible for you. Due to having rods put in my back in 2002 at age 14, I lost the ability to self-transfer from my wheelchair. It was a very necessary surgery, but it wasn’t without its risks. One of which was that I’d lose a bit more strength on top of my already evident muscle weakness due to my muscular dystrophy. That surgery extended my life at a cost, but I’m not embittered by it. Though I do wish things were easier! From this point on I could only be transferred via a hoist or person lifting me. Lifting somebody with MD who also has metal rods in their back can be painful and risky. Not to mention for the PA/carer lifting a grown adult compared to a child can be a health and safety issue… So hoisting it was!

I quickly realized that if I drank normally, I’d need to leave wherever I was abruptly and get home as fast as possible to go to the toilet. I tried to persevere and due to my stubbornness of not wanting to let toileting dictate to me when and for how long I left the house, I developed a system. I did what disabled people do best, adapting to the hand we’ve been dealt, but again it came at a price. A price that didn’t raise its ugly head until many years later…

I quickly realized that if I drank normally, I’d need to leave wherever I was abruptly and get home as fast as possible to go to the toilet. I tried to persevere and due to my stubbornness of not wanting to let toileting dictate to me when and for how long I left the house, I developed a system. I did what disabled people do best, adapting to the hand we’ve been dealt, but again it came at a price. A price that didn’t raise its ugly head until many years later…

In order to go out and enjoy life, through trial and error via what they term “Pee Math,” I learned the only way to go 9-5 without being so desperate I had to abort wherever/whatever I was doing at the time was to limit my fluid intake to a measly 1-and-a-half child-size cups per day. It was a very slow adjustment to get down to that little liquid. If I’d have gone cold turkey, it would have backfired. So over those two years I’d mastered measuring the golden liquid content my bladder could hold all day. I learnt “tricks” to get past the thirst, such as applying lots of lip balm, chewing gum to produce more saliva and distracting myself whenever extreme thirst hit. I thought I had it all figured out. Family would give me a pat on the back and joked about my “bladder of steel!” Foolishly I thought this way of living was sustainable.

The let down once I was finally home and had access to the toilet was excruciatingly painful. My bladder often couldn’t relax; it’d spent all day holding it in and now it only let go in painful dribs and drabs. Often I’d sit for half an hour, holding my lower stomach in pain on the toilet. Yet once it was over I’d persuade myself it wasn’t that bad — because look at all I got to do out and about today! I’d convince myself it was OK to live in pain. It was better (in my mind) than being confined to my home, just for access to a loo I could actually use. Wouldn’t you do similar? A new day would start and I’d do it all over again, and again and again…

Five years into this way of living, it finally started to take its toll on my health. I was 19 and kept getting back-to-back UTIs. I was constantly at the GP for more antibiotics. I’d unintentionally done it to myself, and was what doctors termed “socially incontinent,” meaning I had full bladder control but lacked the ability to physically go to the toilet without a hoist and a PA. The infections were relentless. I was fever struck, hot flashes and constant urgency started to now ruin my ability to go out. Now I had to stay at home by the toilet or risk having public accidents. Now I was in constant UTI-related pain, not just when on the toilet. I saw people less and less. I even opted to wear pads at one point, just so I could try to go out.

My confidence was literally in the toilet and depression clouded my spirit. I am an active person and being chained to a toilet was like my disability was getting one up on me, when all I’d ever felt up to then was acceptance for the way I am. I’m very easygoing by nature and take most things in my stride, but this was beyond me. I saw no way out other than to stay at home, wear nappies or get a hospital-style catheter. What kind of options are those for a young woman?

It wasn’t until I was 21 that “Changing Places” was becoming known through word of mouth in the disability community. Everybody, including me thought this was a huge breakthrough. Finally an accessible toilet for those who need more than just grab rails! Changing Places toilets are spacious. The toilet is clear on either side for carer support if needed. You have a ceiling track hoist that runs over the toilet and across the room over an adult-size adjustable changing table. Basically my exact setup at home, only I get changed on my bed then get hoisted as my bathroom isn’t big enough for its own changing table. The first Changing Places loo I ever used was on a trip to the Trafford Centre and it was amazing! To be able to go shopping and literally “nip to the loo” like everyone else was so empowering. Using that toilet made me feel less disabled then I’d felt in a long time!

Sadly, these toilets are costly and although disabled people are campaigning up and down the country, writing letters to local councils and MPs to get at least one of these accessible toilets in every town/main attraction/shopping centres etc., the reality is they are few and far between. In fact, most able-bodied people don’t know they exist at all.

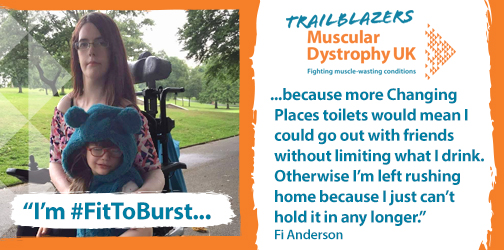

In the meantime the Trafford Centre Changing Places toilet is my local accessible loo and it isn’t exactly local at two hours away. I’m lobbying as a North West Trailblazer to hopefully convince my local council to install one in the town centre etc. but I’m running out of time. Life goes on despite when you endure.

Due to now developing a high resistance to six common antibiotics that target UTI’s and having the “cillins” off the table to me as I’m allergic to all in the penicillin family, I am having to take drastic action. My urologist doesn’t know what will happen when I become resistant to the low dose continuous antibiotic I am on now. At best it’s taken away the burning sensation, but my body is still in a constant state of infection. I’m feverish on and off throughout the week, I’m fatigued, I’m weak and I’m done! Reaching out to others with MD who have lost the ability to self-transfer I learnt there’s a way out of this cycle through getting a suprapubic catheter. Keep in mind I’ve been outright refusing a standard catheter (that goes through the urethra) since I was offered it as a pre-teen as catheters cause infections too, plus I didn’t want a bag attached to me constantly. I still have full bladder function after all. It’d be foolish to knowingly take away an ability my MD hasn’t made me lose just because it’s an easier toileting option. I heard my fellow MD friends out and I realized, this wasn’t about pride anymore. This was about toileting impinging on my quality of life and I felt an SPC would give that and my dignity back. Something I feel I haven’t had for years…

But what’s the difference between a standard catheter and a SPC? A standard catheter (or ISC) goes directly into the urethra and drains your bladder continously into a bag strapped onto your stomach or leg you try to hide under your clothes. A SPC is a catheter that goes into your bladder through a small incision or stoma into your navel area. You have the option of a “flip flo” valve and still feel when you need to urinate. You literally go into bathroom, park your wheelchair next to the loo, hold your catheter tube over the loo and flip the valve to drain. Or you can attach a bag. This gives the user independence in that they no longer have to transfer and some people can manage to operate the valve themselves, therefore becoming in control of their toileting needs again. With a SPC you still have the option to have a wee normally should you want to as well.

I’m now on the waiting list for this operation, a voluntary surgery that is medically unnecessary. The catheter will give me a new lease on life and control over my toileting for the first time since childhood, but there are risks with any surgery with MD. My respiratory system is compromised so I cannot have a general anesthetic; I’ll be awake during the procedure and I need to be on my BiPAP. There is also the risk that due to pain or complications I could end up in ICU with difficulties breathing through my limited lung capacity. Yet these risks with surgery for the SPC are just as risky as carrying on the way I am, eventually running out of treatment options for the infections and potentially ending up with sepsis. That is the bottom line.

All this because I can’t use a standard disabled toilet. It’s mind-boggling. It’s mine and 250,000 other disabled persons’ reality. I bet you can’t fathom going out for a drink with friends and staring at your glass thinking “If I drink the rest, I’ll have to go home to the toilet.”

It’s been a long 14 years but this is me taking control back the only way I can.

Follow this journey on Life of an Ambitious Turtle.