Survivors Celebrate the End of the False Memory Syndrome Foundation After 27 Years

Editor's Note

If you’ve experienced sexual abuse or assault, the following post could be potentially triggering. You can contact The National Sexual Assault Telephone Hotline at 1-800-656-4673.

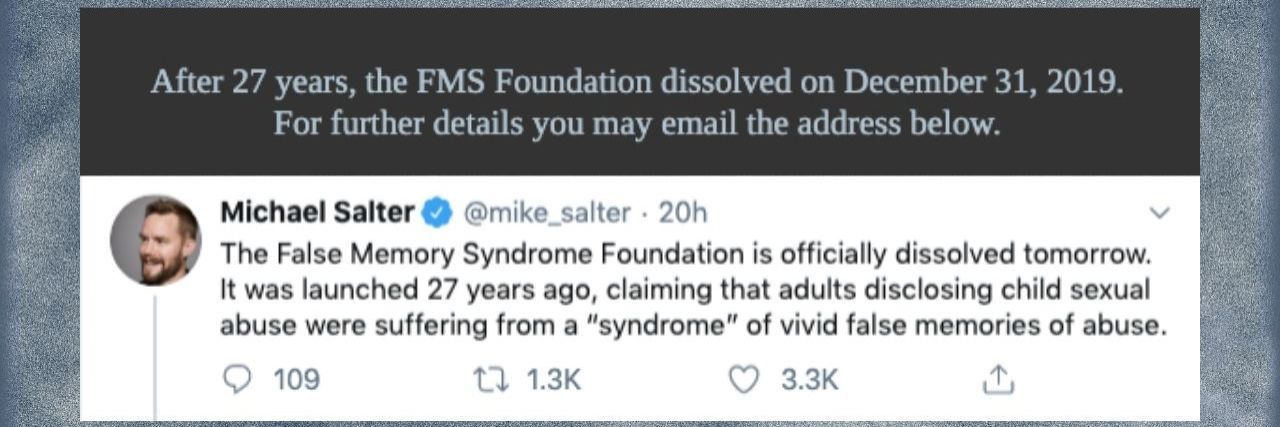

On Tuesday, an institution that worked to systematically discredit countless childhood sexual abuse survivors closed its doors after 27 years. The False Memory Syndrome Foundation quietly announced its dissolution, effective Dec. 31, 2019, in the footer of its website.

The False Memory Syndrome Foundation (FMSF) was founded in 1992 by Pamela Freyd and her husband, Peter Freyd. Peter was accused by his daughter — falsely by his account — of childhood sexual abuse at the height of the repressed or recovered memory controversy in the 1980s and 90s. It offered support to family members who believed they were falsely accused and highlighted memory research from major academics such as Elizabeth Loftus.

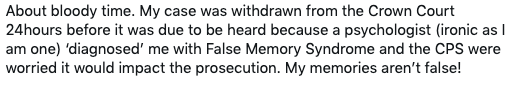

Among its key principles, FMSF elevated Dr. John F. Kihlstrom’s definition of a proposed “false memory syndrome” — which has never been ratified as an actual diagnosis — to question and deconstruct the rise in adults now accusing family members of sexual abuse that never happened. The FMSF amassed heavy hitters in academia and law to help defend family members “falsely” accused of abuse by their adult children, effectively swinging the public narrative to one of mistrust of survivors.

No such “syndrome” exists – it is, ironically enough, a false syndrome. The organization arose to contest law reform in the United States that expanded opportunities for sexual abuse survivors to pursue civil or criminal charges, and then quickly spread to other countries.

— Michael Salter (@mike_salter) December 30, 2019

Upon learning from Michael Salter, a researcher in the area of sexual abuse and complex trauma, about the dissolution of the FMSF, survivors celebrated the end of the organization. They pointed out how the organization’s influence impacted their lives as sexual abuse survivors.

Once it was successfully mobilised against trauma survivors, the notion of "false memories" has been used to undermine other truth claims by vulnerable groups, including survivors of the Stolen Generations and ethnic cleansing.

— Michael Salter (@mike_salter) December 30, 2019

Great news. They were as bad as churches that covered up #abuse.

‘False memory syndrome’ is a fake theory used to undermine abuse survivors & protect perpetrators.

When I studied psychology they taught this crap, but nothing about actual abuse rates or impact. I withdrew. https://t.co/SAdacSRFpB

— Indigo Daya (@IndigoDaya) December 30, 2019

This thread is a huge deal, folks.

False Memory Syndrome was fake psychology, engineered to call into question the childhood sexual abuse #metoo moment of the 1990s.

And today it is gone. https://t.co/3IPqHaqHzf— Steffen Christensen (@Wikisteff) December 30, 2019

But that doesn’t mean that abuse doesn’t happen. We know that. We still just don’t care about the majority of the victims because … I don’t know. So many things. Too many for a twitter thread.

— mossby pomegranate, badass therapist (@angrykittenpaws) December 30, 2019

An organization that did untold damage to survivors of sexual abuse is finally dissolved – there is no such thing as False Memory Syndrome https://t.co/l11P0gmcie

— Iseult White (@iseult) December 30, 2019

While false accusations of abuse and the possibility of remembering abuse that never happened sometimes occurs, it’s not the norm. The American Psychological Association (APA) and other experts said the media played a large role in sensationalizing false narratives. In addition, Salter said in the 1990s, the media glommed on to the rash of “false accusations” but didn’t do a great job of looking critically at the biggest detractors, often academics and lawyers who earned thousands defending against “false” accusations.

“For at least a decade after the Foundation was launched, the media uncritically circulated damaging propaganda from a lobby group of accused abusers,” Salter told The Mighty via email. “Many journalists and members of the public still believe that ‘recovered memories’ are necessarily false despite all scientific evidence to the contrary. It’s going to take a long time to repair the damage and that’s a lesson for all of us on the power of media coverage.”

This obvious conflict of interest went largely unchallenged by journalists at the time. The FMSF catalyzed a 180 degree turn in global media coverage of CSA so that, by the mid-1990s, news stories about CSA focused predominantly on the threat of false allegations.

— Michael Salter (@mike_salter) December 30, 2019

“The issue of repressed or suggested memories has been overreported and sensationalized by the news media,” wrote the APA in an FAQ about memories of abuse, adding:

Media and entertainment portrayals of the memory issue have succeeded in presenting the least likely scenario (that of a total amnesia of a childhood event) as the most likely occurrence. The reality is that most people who are victims of childhood sexual abuse remember all or part of what happened to them.

The APA, along with other organizations such as the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, generally posit that completely repressed memories of childhood sexual abuse are very rare, but can happen. It’s more common survivors will have snippets of memory, triggers or even confusing body sensations like pain of childhood abuse. However, survivors may not put together the narrative completely until later in life, and it may never be complete. More research into the complexity of memory is needed.

Because humans experience trauma as a mind and body fear response, traumatic memory is also stored differently as outlined by scholars like Peter Levine (“Waking the Tiger“) and Bessel van der Kolk (“The Body Keeps the Score“). The stress response shuts down the executive functioning part of the brain during trauma as a survival mechanism. Survivors may remember crisp details right before or after a trauma, but the abuse itself may be blurry.

According to Salter, “about one third of child sexual abuse survivors will experience partial or full amnesia for their abuse.” He added:

This amnesia or delayed recall has multiple sources. As children, they may have dissociated or gone ‘blank’ to cope with their abuse. Shameful feelings prompt many children to avoid thinking about the abuse at all. Children may not know that what happened was abusive due to the manipulations of the perpetrators. All of these processes disrupt memory encoding and recall.

In adulthood, survivors may then encounter triggers that remind them of the abuse and find themselves recalling childhood events that they were previously unaware of. This process is often profoundly distressing and destabilizing. The return of these memories is a common reason for abuse survivors to seek mental health care.

Dr. Christine Blasey Ford explained her own incomplete sexual abuse narrative when its integrity was brought into question while testifying against Judge Brett Kavanaugh. “It’s just basic memory functions, and also just the level of norepinephrine and epinephrine in the brain that … encodes memories into the hippocampus so that trauma-related experience is locked there [while] other memories just drift,” Blasey Ford testified.

Mighty contributor Elyse Brouhard shared the confusion of what it’s like to realize her memory fragments are the result of childhood abuse and the struggle she experienced coming to terms with what happened. Brouhard wrote in the article, “How Admitting the Truth of My Childhood Abuse Is Setting Me Free“:

There are memories and half-memories from my early childhood that I have spent over 20 years telling myself were simply not real. Or that I said just did not add up to mean the things my body and mind kept suggesting they added up to mean.

I told myself I was ‘crazy’ for years. For decades, I called myself a liar and urged myself to stop feeling, stop thinking, stop remembering the things that did not make sense. The things that did not add up to a full picture, but pointed at some pretty disturbing events. I told myself, over and over, to ‘shut up, you crazy girl.’ And I did a damn good job at convincing myself to stay quiet, to stop remembering and to believe that I was, indeed, a little ‘crazy.’

Our understanding of trauma has progressed since the 1990s. What hasn’t changed much is the high rate of childhood sexual abuse and a much higher likelihood these crimes go unreported. According to the National Center for Victims of Crime, approximately one in five girls and one in 20 boys experience sexual abuse before age 17. The National Sexual Violence Resource Center reported only about 12% of childhood sexual abuse cases are reported to authorities.

Though similar active organizations still exist worldwide, many survivors and advocates, in celebrating the end of the False Memory Syndrome Foundation, hope for a more affirmative future for childhood sexual abuse survivors.

“The FMSF closes with a whimper rather than a bang. They have been inactive for many years, with almost half of their advisory board deceased, and many of those still alive in their 80s and 90s,” Salter wrote. “But the legacy of their lies and distortions remain, alongside unanswered questions about media ethics and academic accountability.”

But the legacy of their lies and distortions remain, alongside unanswered questions about media ethics and academic accountability.

— Michael Salter (@mike_salter) December 30, 2019

The Mighty reached out to the False Memory Syndrome Foundation for comment and has yet to hear back.

Article updated Jan. 2, 2020.