Why This Popular 'Comfort Zone' Graphic Doesn't Apply to Trauma Survivors

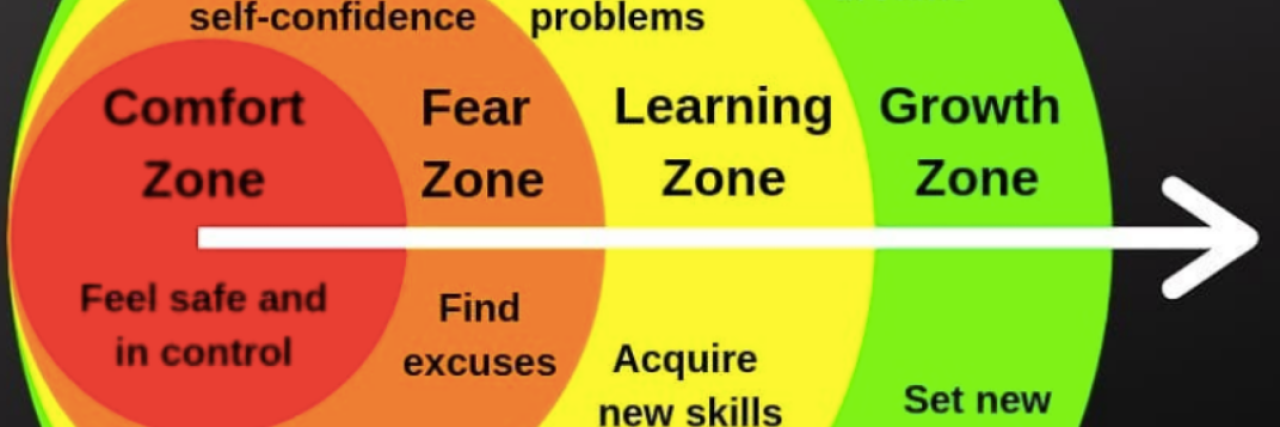

A graphic that explains how to grow through different “comfort zones” recently resurfaced on Instagram, likely providing motivation for people who are trying to push past their “comfort zone” and into their “growth zone.”

According to the graphic — created by personal growth and finance blog The Wealth Hike — the “comfort zone” is characterized by feeling safe and in control, while in the “fear zone” you lack self-confidence, find excuses and are affected by others’ opinions. The “learning zone” is where you deal with challenges and problems, acquire new skills and extend your comfort zone. Lastly, the “growth zone” is characterized by finding purpose, living dreams, setting new goals and conquering objectives. While I recognize this graphic is intended to motivate individuals to push themselves in a professional capacity, it is a very oversimplified perspective of growth and fear, which presents some problems, particularly for survivors of trauma.

Firstly, as a trauma survivor, I don’t have a comfort zone. I don’t ever feel safe and in control the way people who haven’t experienced trauma do. Sometimes just getting out of bed in the morning feels as difficult as moving Mount Everest single-handedly. Every step, every decision and every interaction involves risks of which I am acutely aware.

Does this mean I’ve moved into the fear zone? Not exactly.

I have settings in which I feel safer or more in control, but it isn’t black-and-white, safe or not safe, in control or out of control. For me, those are the settings in which I am most comfortable. Personally, I’m most comfortable at church, sitting in nature, listening to music or spending time with animals. Still, because I am a trauma survivor, I’m continuously processing and often reliving situations that no one should ever have to experience and absolutely no one would find comfortable. I don’t have a linear journey that starts with my version of a comfort zone because the majority of my childhood was completely out of my control and genuinely unsafe. Reliving that would be uncomfortable for anyone, but it doesn’t mean I’m making excuses or intentionally limiting myself — it means I have survived something horrific and the ways my brain processes fear, risk and comfort have all changed as a result.

Some mornings, this one included, I wake up after a night filled with flashbacks and pain and I don’t want to function. I don’t want to get out of bed. I don’t want to do my homework. I don’t want to get something to eat. I don’t want to take a shower. I don’t want to do anything because everything feels terrifyingly unsafe. Sometimes I push myself because there are things I know I need to get done, but sometimes I let myself rest for a bit — and that’s OK too.

For trauma survivors, returning to the things that make them feel more comfortable can be an important part of healing. Because I function with the mindset that everything is unsafe all of the time, returning to those spaces that feel safer and more in my control serve as a reminder that this world can be a good place, that not every experience is going to hurt me the ways I was hurt in the past.

Another unrelatable aspect of this graphic is the way the growth zone is presented, as if it’s a linear process from comfort to fear to learning to growth, with no movement back and forth or overlap between the spaces. It suggests that one must be permanently outside of their comfort zone before they can reach a space similar to what Abraham Maslow referred to as Self-Actualization, or the ability to fulfill one’s greatest potential.

Any successful athlete can tell you how important it is to rest when you’re working really hard. Returning to that semi-comfortable zone is a trauma survivor’s version of rest, which is often also the space in which a survivor is most able to attend to their needs. Without that time and space to be mindful of and attentive to one’s innate needs — which Maslow categorizes in a hierarchy, beginning with physiological needs (food, water, shelter) and ending with “esteem” needs (respect, freedom) — burnout is nearly inevitable and reaching one’s fullest potential is essentially impossible.

That said, as a trauma survivor who stepped back into my semi-comfortable zone just this morning, I have done things that this graphic would categorize in the growth zone. I lived my dream of publishing a book, which was a bestseller. I’m in college studying things I love with a 3.5 GPA as a dual major while working one full-time job, one part-time job and having a freelance writing career. I clearly have goals that I am working towards, some of which I have already achieved. My decision to step back into a more comfortable space this morning doesn’t negate that. It doesn’t mean I’m regressing. In fact, the awareness that I needed some time to step back and the conscious choice to do so was a sign of growth — a testament to the fact that I’ve learned to honor my own limits and take time for myself so I can continue to grow and be the best version of myself.

For trauma survivors, growth and fear can both be messy, complicated topics — and oversimplified models such as this graphic, while well-intended, often lead to misunderstanding and invalidation of our experiences.

To any other trauma survivors out there: know that whatever your journey looks like, it’s OK. It’s OK if you need to rest. It’s OK if you want to push yourself further (but please do so safely). It’s OK. Do whatever you need to do for yourself because you are important and your worth is so much more than your productivity.

Image via @thewealthhike on Instagram