About 10,380 children under the age of 15 in the United States will be diagnosed with cancer in 2015, according to Cancer.org. Cancer is the second leading cause of death in children after accidents.

Despite this, of the $4.9 billion 2014 National Cancer Institute (NCI) budget, only 4 percent went to research around childhood cancer, according to the Coalition Against Childhood Cancer (CAC2).

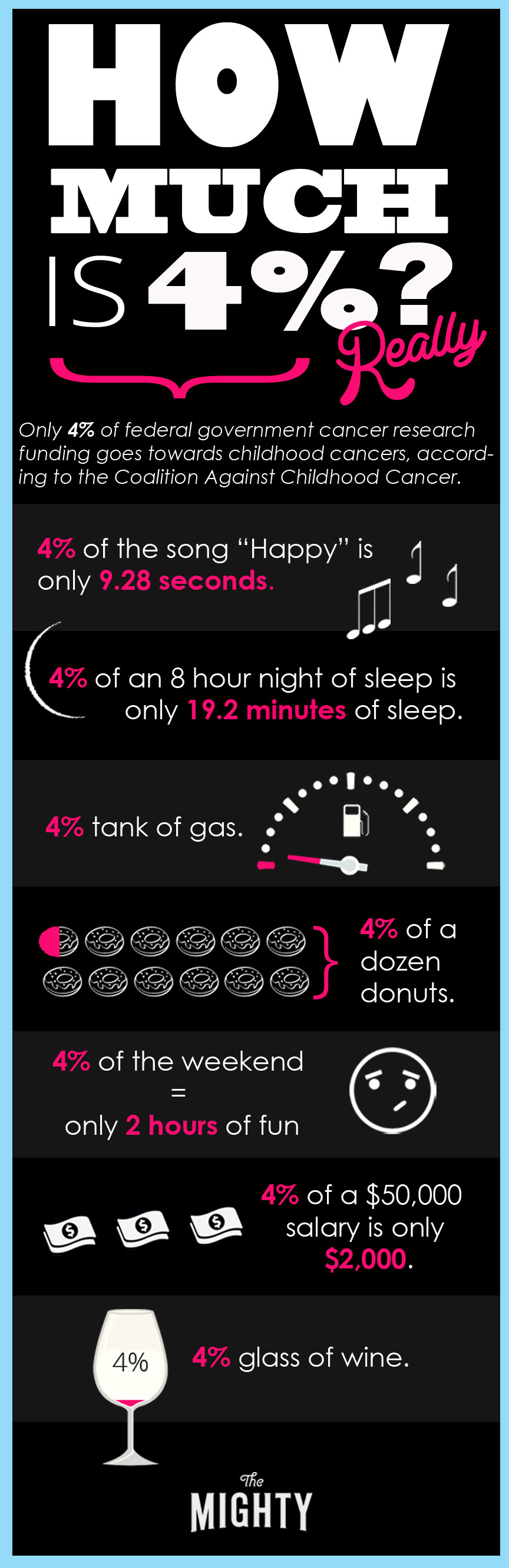

To put that in perspective, this is what 4 percent of something looks like:

According to Vickie Buenger, President of the Coalition Against Childhood Cancer (CAC2), the number itself isn’t the only problem.

“Anytime we start talking about childhood cancer, it is appreciably different from adult cancer,” Buenger told The Mighty. “The causes of the cancers are different, the way they act in the body is different and the treatments for adults may or may not be helpful in children’s cancer because they are affected by different kinds of cancer.”

Because of this, treatment options for children with cancer are often limited and sometimes outdated. Buenger’s own daughter, Erin, who diagnosed with neuroblastoma and passed away in 2009, was at one point taking a medicine that Buenger’s grandmother took as a treatment for breast cancer in the 1970s. Buenger says her daughter spent close to three years of treatment on drugs that were developed in the 1950s and 1960s.

“We were happy to have those drugs because they kept her alive. I don’t want to complain that we had those drugs,” Buenger told The Mighty. “I’m just saying there have only been four or five drugs developed specifically for children.”

Since 1980, only three drugs have been approved in the first instance for use in children, and only four additional new drugs have been approved for use by both adults and children, according to the Coalition Against Childhood Cancers.

This in part has to do with how cancer research is funded.

“The funding picture is incredibly different for adult and children cancers, the difference is that for adult cancers, except for the rarest, there’s also going to be efforts being made not just through federal dollars but also through pharmaceutical companies running clinical trials and trying to do development,” Buenger told The Mighty. “They are using corporate dollars as well as the federal dollars; more than half an annual budget is still being spent by the private sector. In childhood cancer, that is just not true.”

Because children are often diagnosed with rare diseases and the profit pot for pharmaceutical companies developing a drug for a pediatric cancer patient is limited, most of the breakthroughs come from the funding given to childhood cancers by the NCI — the 4 percent.

This means that not only are childhood cancers getting a small portion of federal funding, but they are more dependent on this small portion because developing cures for children’s diseases is seen as less profitable than cures for adults. The financial motivation to develop drugs for children just isn’t there.

“It’s not a matter of raising the [4 percent] number or even doubling it, although that would be nice,” Buenger told The Mighty. “It’s about thinking as a community… My goal as an advocate is making sure children have all kinds of reasons to be a priority so we dont think of them as second-class citizens and we don’t give them 50-year-old medicine. We need to incentivize private industry to think about developing drugs for kids and we need to be a higher priority at the NCI.”

Childhood cancer advocates argue that pediatric cancer should be a higher priority both because other cancers have private funding options and because children have more years of productive life following diagnosis.

“I don’t want to play cancer olympics where we say children are worth more or adults are worth more because I think we’re all affected by cancer,” Buenger told The Mighty. “The 4 percent is the starting point to a question that really has to do with priority for children to take advantage of the great science going on in the United States… We can do better as a nation than we’re doing.”