Liz Atkin Uses Compulsive Skin Picking As Inspiration for Her Artwork

When Liz Atkin was 7 or 8 years old, she began picking her skin. “I was at boarding school away from home and I picked the spots on my upper arms,” Atkins recalled. “I didn’t realize what I was doing until large wounds travelled down both arms.”

The next day a parent of another child at the boarding school Atkin attended asked her what the marks on her arms were. Atkin lied and said she had chicken pox. “It was the first moment the shame and secrecy of the disorder began,” she said. “It’s not just a bad habit, it’s a recognized condition and the guilt, shame and horror of it can be overwhelming. For decades it controlled my life, affected my thoughts, my clothes, my relationships, my work, even my sleep. And I took great care to hide it from everyone.”

Now, Atkin is using the disorder that dominated her life for more than 20 years to create stunning works of art. “[T]hrough a background in dance and theater, I confronted the condition to harness creative repair and recovery,” Atkin, who is based in London, told The Mighty. “I create intimate artworks, photographs and performances exploring the body-focused repetitive behavior of skin picking.”

As Atkin honed in on the physical features of her skin picking, she began to recognize the different ways she was drawn to textures. “I have always been fascinated by peeling paint, lichen, distressed or aging surfaces.” Atkin said. “As I began to turn skin picking into a creative practice I found I was using these influences directly with my skin. I guess I navigate my skin as a soft canvas for imaginative transformation and ultimately healing.”

Much of Atkin’s art represents the body-focused repetitive behaviors of her fingers. For example, Atkin describes clicking the button on her camera as similar to the repetitive picking movement of her fingers. She also uses textural materials like latex, clay and acrylic paint to transform and re-imagine her skin, as well as capture feelings of depression and anxiety.

“The very places I used to pick, my face, my chest, my back, become the places transformed,” she said. “I take many thousands of photographs, so the hours of zoning out in skin picking is replaced by the mindfulness of hours of making. The bathroom becomes an art studio for me, instead of a place of picking.”

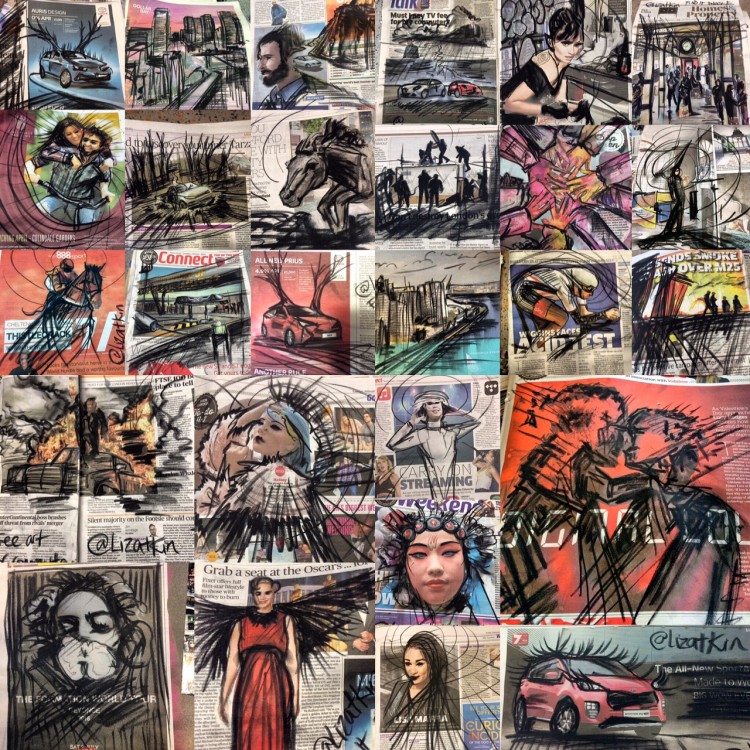

In addition to her picking-inspired artwork, Atkin creates works of art using newspaper and charcoal during her commute. “In 2015, I started giving away drawings on public transport in London,” Atkin said. “I have a long commute on three trains from Forest Hill to East Finchley twice a week, and I started taking a sketch book with me to draw. I ran out of paper on one of these journeys and picked up a newspaper beside me to draw as I realized the carriage was littered with them.”

Each of Atkin’s subway drawings takes one minute, allowing her to create a lot of artwork and minimize the amount of time she spends picking her skin. “Commuters are often intrigued and I began handing finished drawings to someone or leaving them on the floor. It delights people!”

“[Compulsive skin picking] is likely to be a permanent companion in my life,” Atkin said. “I can’t imagine life without it. I’ve had it longer than I haven’t had it, so it’s something that is part of me. Sounds strange but I wouldn’t want to lose it. I’ve had to learn to accept it, and in fact I have found value in it through my art.”