Why I'm Reclaiming the Word 'Fat' in Eating Disorder Recovery

Editor’s note: If you live with an eating disorder, the following post could be potentially triggering. You can contact the Crisis Text Line by texting “NEDA” to 741-741.

I had a major surgery on July 17. I tell everyone that it was for polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), unable to admit that while this is true, I’m omitting the fact that it was also a bariatric surgery. This feels embarrassing and shameful — that I allowed my body, myself, to become so out of control that an operation was my only way out.

Of course, I know this is my eating disorder voice. This, right here, is the hardest part of my recovery. You can learn to nurture your body instead of denying it, to accept that you are perhaps worth something besides the number on the scale and how little you are able to eat, but this voice, the one that whispers “you are disgusting, too much, out of control and therefore a bane on society,” never really goes away. You learn to ignore her, to offset her cruel words with positive reinforcements and self-care, but she is always there, lurking in the shadows.

Having an eating disorder, for me, is what I imagine it’s like to be an addict. You have a predisposition for this particular way of dealing with things. Alcoholics turn to liquor and drug addicts turn drugs, but you turn to numbers and scales and cutting your food into tiny pieces and chewing and spitting and lying — oh, the lying! You and the alcoholics and drug addicts have that in common as well. And you are always “in recovery” because being triggered and going back to that method of dealing with your sadness or anxiety is always there, waiting for you to slip back into it, like your favorite pair of old tennis shoes you know offer no support but are comfortable and familiar nonetheless.

She never had a name. I didn’t call her Ana or Mia or Ed, but she was a part of me and, what I thought for a long time was the better part. And I did learn to set her aside, that I would rather live in the real world than merely exist in my wonderland, but she never disappeared completely, the way I tried to. I still hear those whispers, getting louder at my most insecure moments: “He would love you if you were thin.” “You would have gotten that promotion if you weren’t so fat.” “She wouldn’t have discarded you like a piece of trash if you had your weight under control.” And sometimes it can be hard to ignore her, since I know there is a grain of truth in her malicious words.

Because, in fact, the world can be just as cruel as she is.

Numerous studies have documented harmful weight-based stereotypes that fat people are lazy, weak-willed, unsuccessful, unintelligent and lack self-discipline. These stereotypes give way to stigma, prejudice and discrimination against fat people in the workplace, health care facilities, the mass media, interpersonal relationships and more.

- Fat people get fewer promotions and may receive up to 6 percent less earnings than thin people. Women are up to 16 times more likely to receive weight discrimination in the workplace than men. (In fact, women overall experience higher levels of weight stigmatization than men, even at lower levels of excess weight.)

- Fat people often experience prejudice, apathy and lower quality of care from medical professionals, which may result in patients choosing to delay or forgo crucial preventative care to avoid additional humiliation. 31 percent of nurses in one study said they would prefer not to treat a fat patient.

- Children as young as 4 are reluctant to make friends with an overweight child.

- Defendants in lawsuits who are fat are more likely to be found guilty.

- More than half (61 percent) of people see no harm in making negative comments about a person’s weight.

- Research examining political candidates has found that overweight female candidates receive lower ratings of reliability, dependability, honesty, ability to inspire and ability to perform at their job than non-overweight female candidates. (This finding did not hold true for men.)

- Federal law does not make it illegal to discriminate against people based on their weight. Let me break that down for you: that means if my employer decided to fire me because I’m fat or my landlord decided not to let me renew the lease on my apartment because of my weight, they could, and I wouldn’t be able to fight it.

I am not telling you this so you feel sorry for fat people, and especially not so you feel sorry for me. As a white woman, albeit fat, I have significantly more privilege than some. But when the world reinforces the words you hear from your eating disorder — words that aren’t supposed to be true — it confuses things. Because while she may have been lying when she told me I was much too fat all those years ago, we both know she isn’t lying now.

This word — “fat” — has been one I’ve avoided all my life, ranking it up there with racial and homophobic slurs as words I would never dream of using, that I stiffen at when I hear others say. Historically, I have undoubtedly used the actual “F” word more than this one (sorry Mom.) “Fat” is a reflection of my shortcomings, my deepest fears, my biggest (pun intended) insecurity.

On an episode of “This American Life” last year, Lindy West tackled this issue when she described “coming out” as fat:

“I always felt like if I didn’t mention it that maybe people wouldn’t notice. Or it could just be this sort of polite secret, like, open secret that we didn’t address, because it felt so shameful. It just felt impolite to talk about, like me not wanting to burden you with my failure.”

But this stigma of the word “fat” enables the continued stigmatization of fat people. It also gives my eating disorder voice power when I equate the word “fat” with shame, instead of merely an accurate descriptor of my body. So I’m joining others in taking the word “fat” back. I am fat. I am in recovery from anorexia. These things aren’t mutually exclusive. And that’s OK.

Follow this journey here.

If you or someone you know is struggling with an eating disorder, you can call the National Eating Disorders Association Helpline at 1-800-931-2237.

We want to hear your story. Become a Mighty contributor here.

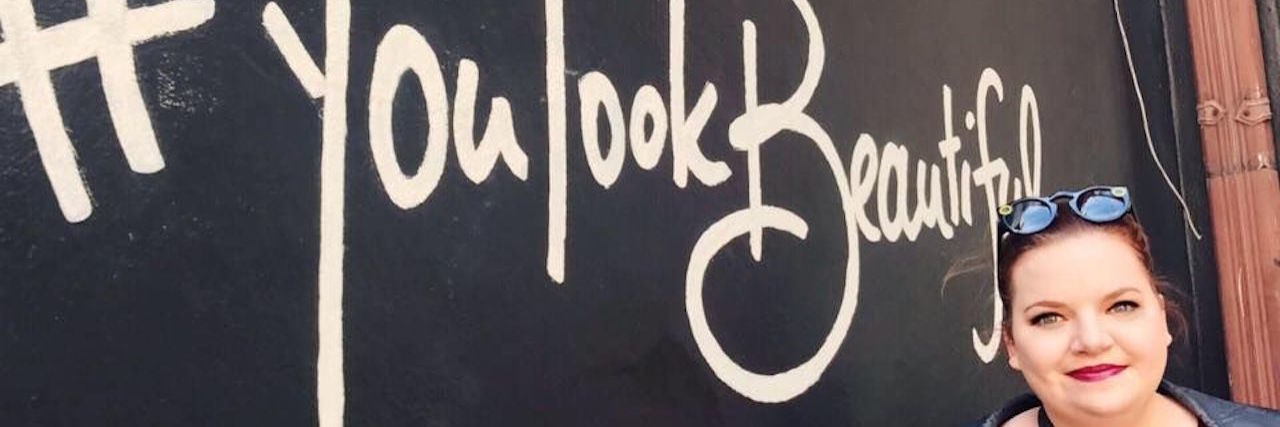

Lead image via contributor