Why This Televangelist's Comments About Mental Health and the Texas Shooting Are So Problematic

Sometimes the news isn’t as straightforward as it’s made to seem. Juliette Virzi, The Mighty’s Associate Mental Health Editor, explains what to keep in mind if you see this topic or similar stories in your newsfeed. This is The Mighty Takeaway.

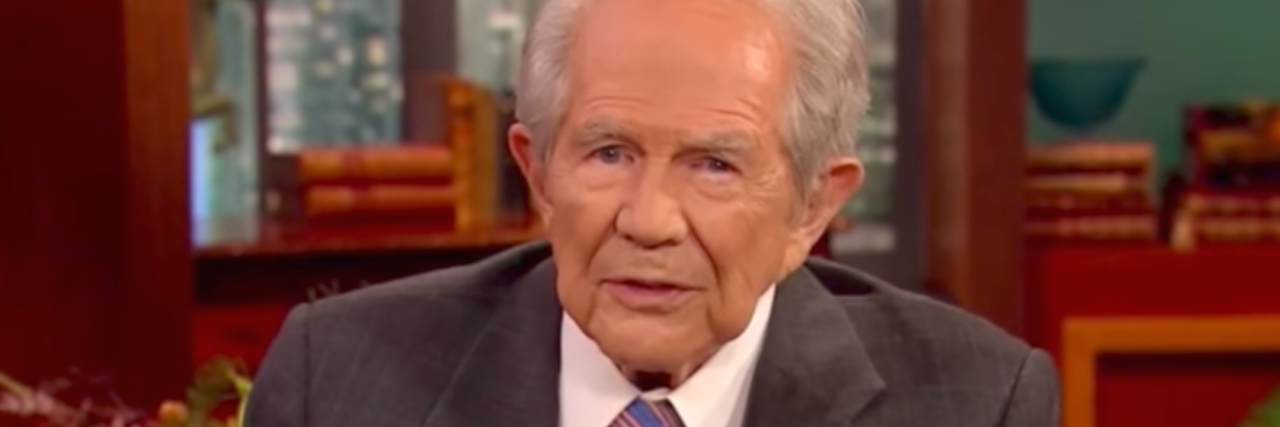

On Monday’s episode of “The 700 Club,” a talkshow on the Christian Broadcasting Network, televangelist and host Pat Robertson called for an investigation into the link between antidepressant drugs and mass killings in the wake of the Texas shooting.

There’s got to be a thorough investigation into the effect of antidepressants… There’ve been so many of these mass killings and almost every one, as I said before, has had some nexus to antidepressants. So, we need to see what we are giving people.

In the wake of tragedy, it’s common to look for an explanation — and unfortunately, people often jump to link mental illness or psychiatric drugs with violence. Pat Robertson certainly isn’t the first (and won’t be the last) to point the finger at antidepressants, but when well-known Christian leaders make claims like these, it hurts Christians struggling with mental illness, and we need to talk about it.

Though we know gunman Devin Patrick Kelley was indeed hospitalized for mental illness in the past, it’s important to note there has been no confirmation that he was on antidepressants or any other psychiatric medication.

But do antidepressants actually increase violent behaviors and thoughts?

The Mighty spoke with John R. DeQuardo, MD, a distinguished fellow from the American Psychiatric Association and a senior instructor at the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center’s psychiatry department. Countering Robertson’s comments, he said,

In my mind, there is no link between antidepressant medication and mass shootings, period. In fact, the evidence would be just as good for religious fervor and mass shootings as it would be for antidepressant medications. People like to jump to knee-jerk causality in these kind of things, much like people say, ‘we should do more gun control’ and I don’t know if that’s the answer either. Certainly stopping treating people for depression is not the answer to mass shootings.

Perpetuating the idea that being on antidepressants automatically equals violent behavior is not only damaging, it’s a tenuous argument at best. Since they were first introduced almost 70 years ago, antidepressants have been prescribed to millions of people. It’s unfair to blame the current wave of gun violence on antidepressants when there are other variables that factor into a person’s propensity to commit an act of violence. In an article examining international comparisons of mass shootings, The New York Times found that access to guns was the most likely factor in higher gun violence in the U.S., with the U.S. owning 42 percent of the world’s guns.

In an interview with Newsweek, Carmine Pariante, professor of biological psychiatry at the King’s College London’s Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, stated that the claim that antidepressants cause violence could also be explained by chance.

There is no good evidence that antidepressants increase the risk of violent behavior, and the extremely rare (and tragic) cases that are cited in support of this theory could be explained by chance: antidepressants are prescribed relatively widely, and so by chance someone on antidepressants will commit a violent act. Moreover, people on antidepressants may be suffering from some forms of mental disorder or distress that may, albeit very occasionally, increase the risk of reacting impulsively or violently.

But if we put aside Robertson’s comments about antidepressants for a moment, we can see the problem goes much deeper than his distrust of psychiatric medication. It’s Robertson’s framing of mental illness, in general, that is so damaging:

Our hearts just break at the thought of innocent people in a tiny church in a little tiny city in Texas… here these people have come on Sunday morning to worship God and to pray and to receive communion and whatever else they did, and here they are innocently in this building, and this evil man comes in their midst — but he’s mentally unstable.

The juxtaposition of the tangible innocence Robertson depicts with the “evil man” who is “mentally unstable” is a prime example of the “othering” people with mental illness often face. By setting up the situation in this way, Robertson implies the gunman is evil not just because he killed 26 people, but because he’s also “mentally unstable.”

While this implication isn’t anything new (people with mental illnesses have faced systemic discrimination for decades), it’s significant because a prominent Christian leader said it. And when religious leaders talk about mental health in a damaging way, we need to call them out on it.

Christian pastor Steve Austin, who speaks candidly about his own experiences with depression and a suicide attempt, is no stranger to the stigma Christians with mental illness can face. “The Church is hesitant to admit that I can be a faithful person and also need medication, counseling and maybe even hospitalization,” he said.

When a famous religious leader like Robertson implies that taking psychiatric medication leads to violence, it can keep people from exploring medication as a possible treatment option, as well as prevent them from opening up at all. This is a big deal because people often seek help related to their mental health from the leaders of their religious communities. In a study on patterns of people contacting clergy members for mental disorders, it was found that a quarter of people who ever sought treatment for a mental health struggle went to a clergy member.

Unfortunately, the Church has a history of discussing mental health poorly — or not discussing it at all. Of his own experiences, Austin said,

In the fundamental churches where I grew up, no one talked about psychiatric medication like antidepressants. In the circles I was raised in, mental illness was equated with demonic possession. If you mentioned depression, for instance, during a prayer service in the church where I was raised, a team of people would prep to cast out a demon.

In addition to the societal stigma of mental illness, many Christians face stigma specific to Christian culture. For example, in my own experience as a Christian, I’ve been told my depression is a sin and a result of not praying enough — words that further isolated me in my struggle.

“It’s important for church leaders to talk about mental health in a non-stigmatizing way because we get plenty of stigma everywhere else,” Austin told The Mighty. We need to hold religious leaders like Pat Robertson accountable when they make uninformed comments about antidepressants and mental illness because it sets a precedent for how churches everywhere have conversations about mental health.

This is the kind of stigma that can make people feel unloved by God for struggling with their mental health. This is the kind of stigma that makes people ashamed when their prayers don’t “cure” their depression. This is the kind of stigma that keeps people from reaching out for help when they need it the most.

If you are a Christian experiencing mental health difficulties, Steve Austin has some words of encouragement for you.

If you’re a Christian who is struggling with mental health, know this: you are enough. And you are loved. Life is messy and sometimes the days are really hard, but I am living proof that no matter how hard life gets, no matter how much you feel like an outcast, we always have a path to grace. If you are anything like me, that path is often winding and unpredictable, but it’s worth the fight.

If you or someone you know needs help, visit our suicide prevention resources page.

If you need support right now, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 or text “START” to 741-741.

Image via Right Wing Watch YouTube Channel