I’ve had a chronic illness since 2002. It’s what I have, what I have had and what I will continue to have for, as the name suggests, chronos – or, a lifetime.

There is a kind of deep discomfort that others exert in the presence of someone with a chronic illness. Erene Stergiopoulos touches on this in “The New Chronic” where she distinguishes between the acute and the chronic. She writes how acute illnesses encourage short-term, intense compassion that culminates in the inevitable outcome of life or death, but culminates nevertheless. There is something so exhausting, then, with the idea of sustaining said compassion long-term, as is the case with chronic illnesses.

We’re the exception to the life-or-death culmination of compassion. We’re permanent occupants of the liminal space between life and death.

With chronic illness there is also so much inconsistence within the consistence. The existence of the condition remains stable but how it manifests sees drastic ebbs and flows. Tasks can be manageable one minute and impossible to complete the next, making participation in capitalism a constant Sisyphean battle.

Capitalism is structured at the expense of marginalized groups. Capitalism functions as per the production it can create. We are all workers and consumers, and our value is contingent on the labor we exert and the expenditure of the resultant earnings. However, people with chronic illnesses can often participate in neither. In Australia in 2012 almost half of all people with chronic conditions were not working. Even when we are active in the labor force, in America we earn .63 cents per one dollar an able-bodied person would make. In Australia the relative income of those with chronic illnesses and disabilities is approximately 70 percent of those without.

Capitalism hates people with chronic illnesses and disabilities because we cannot be utilized, and because keeping us alive costs billions of tax dollars.

Let’s consider then how chronic conditions intersect with other manifestations of marginalization. Let’s consider the position this puts us in. Women with disabilities have a higher likelihood of experiencing domestic violence, sexual assault, rape, neglect and negligence, maltreatment and exploitation, and the instances in which these acts occur are almost never reported. Capitalism sets the standard for how we can be treated – dehumanized and disregarded with great ease. Let’s think then about disabled people of color. Let’s think about disabled women of color. Let’s think about disabled, queer women of color. Think about Stephon Watts. Think about Charleena Lyles. Think about Magdien Sanchez. Think about Laquan McDonald.

People with chronic illnesses and disabilities aren’t just pushed to the margins at the hands of capitalism, we’re pushed to the margins at the hands of anti-capitalism too. Anti-capitalistic movements often fail to consider the participation of their sick and disabled friends. Johanna Hedva articulated best when she lamented on how people for “whom these protests are for, are not able to participate in them” and thus are rendered invisible in such movements.

In 2014 I visited a friend at a crust punk occupied space where I was fed dumpster dived beer. I thought it was so cool and anti-establishment until I got sick. In late 2015 I went to a warehouse rave with no toilet and no mention of this on the event page. I have a gastrointestinal disorder. In 2016 I went to an anti-racism protest where I was in too much pain to continue standing upright. I kept standing upright. I was in bed, bruised, for almost a week. What else could I do?

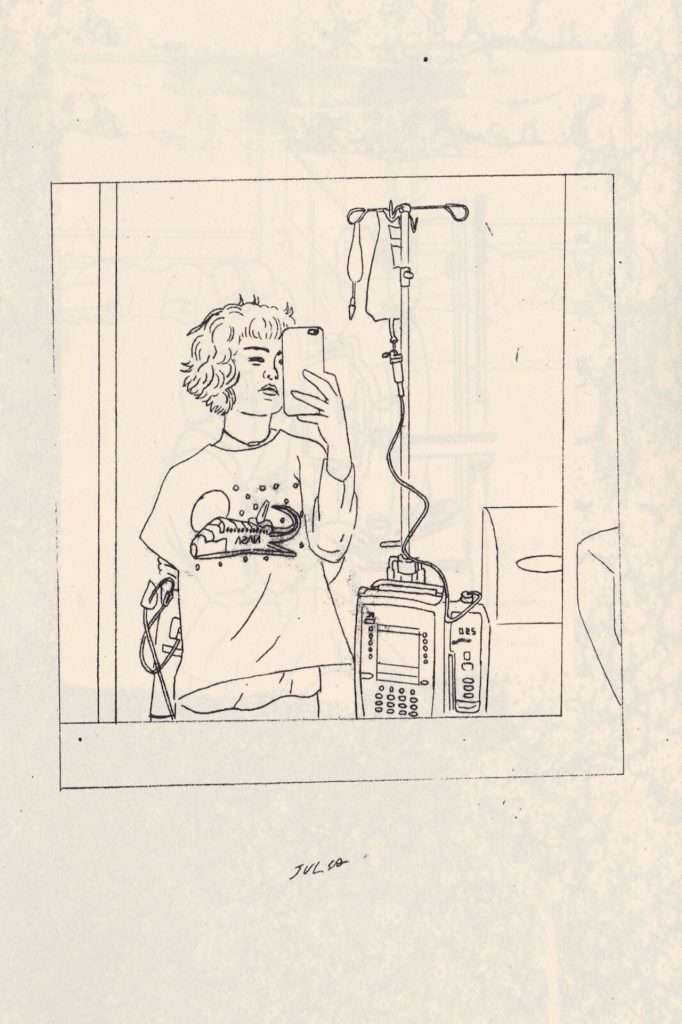

Queer spaces, which often pride themselves on being inclusive, aren’t much easier to navigate. Where in Melbourne queerness has been conflated – with or without intention – with club culture, there is little room for people like us. I’ve seen time and time again friends of mine fade into the margins following either the diagnosis of a new illness or the flare-up of an old one. We get likes on Instagram for our bed or hospital selfies. We get likes on Facebook when we share articles on ableism. We get likes on Twitter for our short quips about the pains of being in pain. What we don’t get is actual, tangible support.

The current means in which able-bodied queer people thrive in Melbourne isn’t conducive to the experience of a sick or disabled person. For a lot of us it’s inaccessible, it’s unattainable and it feels as though there’s no other option if we want to be not just seen and heard but remembered in the queer scene.

What’s great though is the emergence of networks that allow people with chronic conditions to connect, communicate and organize. What’s even better is the resistance I see from sick people in their respective mediums. I see creative expression with unabashed acknowledgement of our limitations in our production. I see groups forming on Facebook that are ours, where we can prioritize each other and ourselves from the comfort of our bedrooms.

I see me writing this in bed, in pain, and I see someone reading it and feeling that long overdue sense of connection. Our worth is not contingent on our production – our worth is our selves, our love, our hope, our anger and our drive. As a collective we are going to accomplish incredible feats through resisting the notion that we cannot resist the notion.

What we need is for people to unlearn their discomfort towards us and create environments in which we can co-exist and flourish. So listen to Johanna Hedva. Listen to Angel Powell. Listen to s.e. smith. Listen to Annie Segarra. Listen to Jax Jacki Brown. Listen to Kay Ulanday Barrett. Listen to Leah Lakshmi Piepzna- Samarasinha. Learn their names. Listen to and learn from them.

Because disabled people and people with chronic illnesses are warriors. We will never be able to stop fighting. We might be bed-ridden, we might subsist on a diet of whatever’s closest and we might have all the mugs in our bedrooms, but our existence is strong, and our resistance is – and will continue to be – even stronger.

Illustration by Grant Gronewold