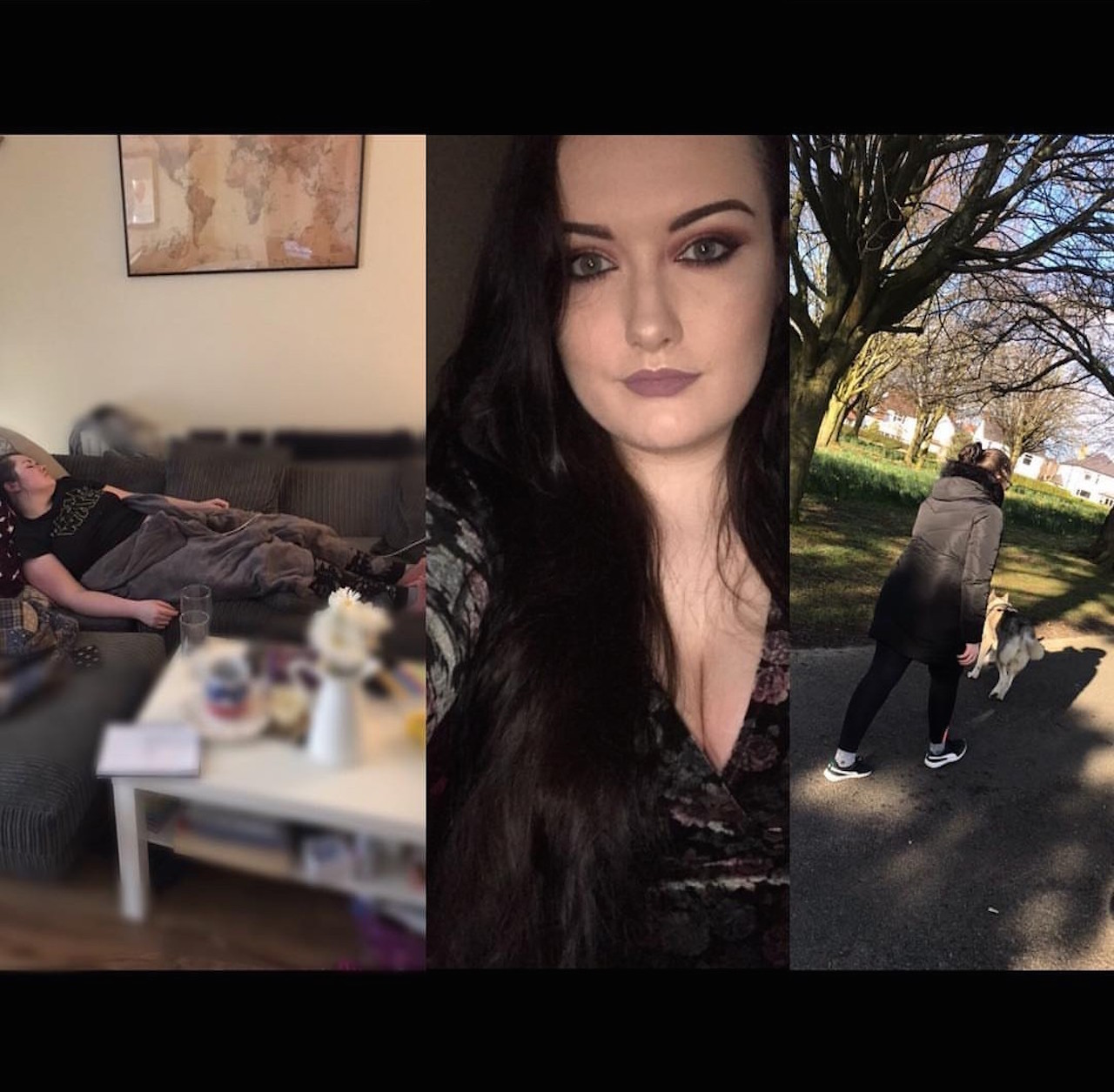

To make myself feel better on days I’m able, I put on makeup. On countless occasions, I and people I know, have been told by the doctor they look well when they come with mental health issues – as if the only form a mentally ill person comes in is unwashed, greasy hair, in sweats and no makeup. The same applies to the chronically ill. Having an invisible illness, doctors and assessors for disability benefits look for physical indicators like the ones I’ve just mentioned, and if you don’t fit the bill you aren’t taken seriously. Even when you do, sometimes you’re not taken seriously because there’s no tangible evidence. That’s why I present these three pictures side by side, taken over the space of 48 hours. I’m just as ill in all these pictures, just varying degrees of severity, a common occurrence in chronic or mental illness.

People can’t comprehend that the look of our illnesses vary from one day to the next. We get the authenticity of our claim to illness questioned when we’re seen doing something normal; when we’re seen shopping, out for dinner, out a walk or on a night out. Usually this is because we’ve turned down plans with someone that is healthy, or we’re seeking help from a doctor or we’re being assessed for benefits. However, just as our illnesses are invisible, so are the preparations and compromises we make to do these tasks.

If I go shopping it has to be short or it will result in a flare. If I go clubbing (which is a rare occurrence these days), I dance sitting down – as funny as that may sound. When out for a walk I can’t go far anymore or, again, it will result in a flare.

If I’m to attend a gathering with friends or family, I have to rest intensely days before, and even then my body may not permit it. Like Christmas, for example. I got to see my mum a week before, yet on Christmas Day I didn’t get to see my dad and the rest of my family because my body was in a massive flare. Giving myself a week to rest can sometimes not even be enough. We are not unpredictable, but our illnesses are, and this is harder for healthy people to understand because all they have to go on is our word. It creates strains on relationships because they cast a shadow of doubt on our claim to illness. When they don’t understand our reasons to cancel or why our activity levels vary, it implies doubt and questions the integrity of our character.

When this comes from friends and family, it is hurtful. However, we expect this from the welfare system – it is their job to question our integrity. Their knowledge base of chronic and mental illness leaves something to be desired. Having been through the assessment process and knowing the criteria to qualify as disabled, it is disappointingly flawed. Through this process I heard the stories of many others and of how my chances would be lessened if I wore makeup, if I dressed up, along with many other things. I ignored all this and intended to act and look how I do on any given day. However, that morning I woke up exhausted and in a pain.

During the appointment I was wearing my pajamas, no makeup, hadn’t showered because my pain flare was in its third day and my electric blanket was wrapped around the lower part of my body. On the plus side I was having a good mental health day. I was able to explain everything out well with only a little brain fog, which I was proud of. Little did I know, this would be to the detriment of my case.

I was declined based on the fact I said I had mobility problems, yet I was able to retrieve my passport five steps to the kitchen at a normal speed, could touch my knees and head while standing, and the fact I didn’t display my cognitive difficulties and mental illness symptoms that day.

The phrasing was the worst thing, he wrote, “you say you can’t…I say you can” before and after every mobility difficulty I claimed to have. I don’t think I’ve ever felt as invalidated in my life. This decision perpetuated my self-esteem, confidence and self-worth issues, which were initiated by my previous doubtful, negligent doctors. My deepest fears were realized – it’s all in my head.

These were all my first intrusive thoughts, so I turned to my boyfriend and he reminded me of my daily struggles and therefore I didn’t give depression a chance to sink its claws in. If I had not got that support I may have given into my immediate self-destructive urges, to prove to myself just how ill I was by doing housework, walking the dogs, cooking until I couldn’t stand the pain anymore, creating the biggest pain flare I’d ever had. These intrusive thoughts being just another blatant indicator of my mental illness.

Having an invisible illness is difficult, especially at the age of 24.

Unless you have to crawl from place to place at my age, you’re OK.

Unless people can see what ails you, you’re OK.

Unless you’re crying in front of them in pain, you’re OK.

Unless you’re unable to answer them, your cognitive function is OK.

Unless you’re hysterical or shaking in fear, your depression or anxiety is OK.

The system is tragically flawed. It’s designed to make even those of us that are truly ill jump through hoops until we lose our resolve and give up our fight for help. If they cannot see it for themselves, it doesn’t exist and this causes mental harm in the process that we carry with us.

The fact you have good and bad days as a spoonie works against you.

The fact your mental health fluctuates works against you – and should you show no stereotypical physical signs of these in your 30 minute appointment with your doctor or assessor, then you are denied help.

We slip in and out of pain flares just like our mental health rises and falls therefore the look of chronic illness fluctuates also. There is nothing linear about our journeys through these illnesses, nothing black and white. However, this is all that the system recognizes.

They look at invisible illnesses as an attempt to cheat the system. They don’t look at us the same as a visibly physically disabled person because they check out on paper, and we don’t. Therefore should there not be a different process to follow, one in which we aren’t affected by anxiety in trying to prove that we have an illness you cannot see? A process that monitors and assesses us a different way than a half hour appointment in which we may be feeling relatively OK? For us, 30 minutes could be all it takes for our condition to flare-up, resulting in immobility for days or weeks on end.

How are our family and friends supposed to understand invisible illness when the healthcare system doesn’t? This will only change through open conversation – more articles, blogs and social media posts. We have to stand together.

“The only way that things are going to change is if people can see us.” – Jen Brea (“Unrest”)

This is why I choose to be radically authentic and open in my struggle with my chronic and mental illnesses; we create change first and foremost with ourselves.

Follow this journey on Instagram.