28 Years After the ADA, People With Disabilities Have Come a Long Way, but the Fight Isn't Over

Sometimes the news isn’t as straightforward as it’s made to seem. Karin Willison, The Mighty’s Disability Editor, explains what to keep in mind if you see this topic or similar stories in your newsfeed. This is The Mighty Takeaway.

July 26, 2018 is the 28th anniversary of the passage of the Americans With Disabilities Act. As we mark this momentous occasion, which has led to so many changes and opportunities for our Mighty community and beyond, let’s take a moment to look back to see how far we’ve come and forward at where we need to go.

The Americans With Disabilities Act was the result of decades of social change and activism by people with disabilities demanding our rights. Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act was among the first laws protecting the rights of people with disabilities, but activists had to occupy government offices to force the Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare to sign the regulations. This was recreated in a recent episode of “Drunk History.”

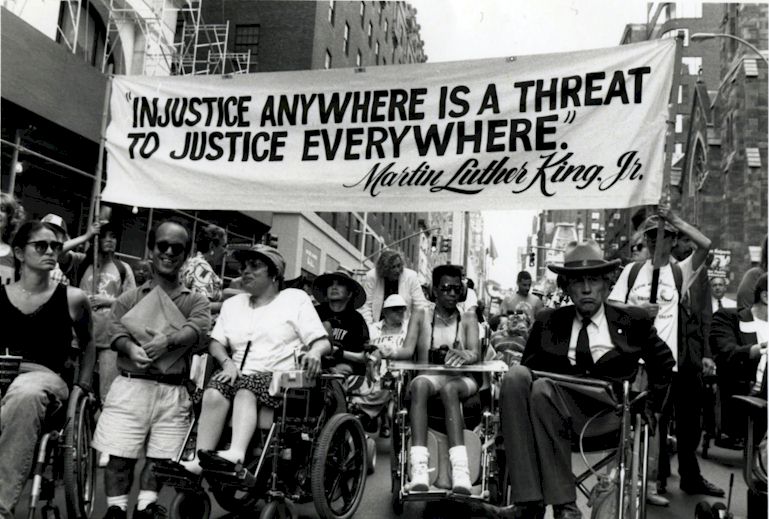

Across the country, disability activists adopted the principles of nonviolent civil disobedience and began blocking inaccessible entrances and buses to draw attention to the discrimination they faced. This black-and-white photograph shows demonstrators, mostly in wheelchairs, blocking transit buses in 1990.

At Gallaudet University in 1988, students leading the Deaf President Now movement fought to have leaders who were part of their community, an example of the “Nothing about us without us” philosophy that is a core part of the disability rights movement today.

In the 1980s, polio survivor Justin Dart (often referred to as the Father of the ADA) and his wife Yoshiko traveled around the United States talking to people with disabilities and documenting the injustices they faced. Using the information the Darts collected, Senator Tom Harkin and other lawmakers drafted the ADA and began working to secure its passage. The path wasn’t easy, though, and the bill eventually stalled in a congressional committee.

On March 12, 1990, over 1000 disability activists, including Dart, gathered in Washington to demand passage of the Americans With Disabilities Act. After a day of marches and speeches, 60 of those activists got out of their wheelchairs and crawled up the steps of the Capitol to show the barriers they faced every day.

This powerful demonstration pressured Congress to move forward and pass the ADA. Everyone with a disability reading this today should take a moment to remember these activists, many of whom are no longer with us, and honor their bravery and sacrifices.

I remember a time before the ADA, and I’ve lived through the transition period and the gradual evolution in the way society views disability. When I started school, it was still common for children with physical disabilities to be segregated, and my mother had to fight for me to be mainstreamed into regular classes. I remember being aware of how inaccessible the world could be. I remember going into restaurants through the kitchens and into theaters through the backstages. I remember being in a class where we were supposed to learn to read a bus schedule, and I said it didn’t matter if I learned because the buses were not wheelchair accessible anyway. I felt strongly that I wanted to accomplish big things in life, but I knew the world wouldn’t make it easy.

I was in middle school when the Americans With Disabilities Act was signed into law. I can instantly recall the iconic image of President George H.W. Bush signing the law as Dart and other disability rights leaders looked on.

My mother understood what an important moment it was for our country and for her daughter. It helped her transition from struggling with grief about her daughter’s disability into an outspoken leader in the disability rights movement. She fought to make sure the ADA was enforced in our community and taught me to accept myself and demand equal rights with the powerful new law backing me up. This is my personal story, but it was repeated in small towns and big cities all over the country where people with disabilities and our loved ones realized we had the power to create change.

I have a friend whose daughter has cerebral palsy and reminds me of myself. She is about the same age I was when the ADA was signed. She has grown up in a world where curb cuts are expected, even if they aren’t always present. She has been able to access many public restrooms without having to be carried from outside the stall. She can roll onto a bus and get where she needs to go. She can eat at restaurants with her family, have a good view at the movie theater, go to college someday, and simply exist in the world. It won’t be easy for her, but it’s easier than it used to be. People with disabilities are part of the community now, and seeing us out and about is normal.

It’s clear the ADA has brought about tremendous changes for people with disabilities in certain areas. However, in other respects, we still have a long way to go. There is still tremendous ignorance surrounding invisible disabilities. People accept wheelchairs, scooters and walkers more readily and usually welcome guide and service dogs. But people whose disabilities are less apparent are continually doubted and sometimes accused of taking things away from people with visible disabilities. People with invisible disabilities have just as much right under the ADA to do things like use accessible parking spaces and receive reasonable accommodations at work. We need to acknowledge and accept all disabilities and believe people with disabilities about their needs. So as we move forward into the next 25 years of the ADA, let’s make sure this group of people won’t be left behind.

People with disabilities cannot rest on our laurels and take the ADA for granted. Earlier this year a bill designed to weaken the ADA passed the House of Representatives, but thankfully did not get through the Senate. This bill would have required people with disabilities to notify businesses before filing a lawsuit over inaccessibility and allow businesses to delay making access changes for months or even years. I don’t know about you, but I think 28 years is plenty of time to comply with the law.

Those who supported the bill said it was designed to reduce the number of so-called frivolous lawsuits over inaccessibility. But the vast majority of ADA lawsuits are not about things like a parking space that is two inches too narrow or a grab bar mounted an inch too high. They don’t need to be, because thousands of companies and municipalities around the United States are currently getting away with flagrant ADA violations. They are operating businesses which are not wheelchair accessible because of just one or two steps. They are refusing to provide caption systems or interpreters for deaf people. They are running taxi and rideshare services with no accessible vehicles and with drivers who will cancel rides and leave behind blind customers or people who have a service dog. In some cases, they are major cities with massive budgets that continue to have inaccessible subways and poorly functioning paratransit systems.

I call these kinds of blatant acts of discrimination “inexcusable inaccessibility.” They could easily have been fixed over the last 28 years, but those responsible have chosen not to do so. I believe they should be an important focus of activism and action going forward. To fully achieve the promise of the ADA, we need to make accessibility universal so in every city and small town, people with disabilities can plan a trip to go shopping and out to dinner without having to call ahead to check on accessibility or worry about how they will get there and back.

Today, people with disabilities are often less held back by physical inaccessibility and more held back by individual and systemic attitudes. We rely on a broken and outdated system to get the services we need, and that very system makes it difficult for us to use the rights the ADA affords us. We have the right to work, but getting disability benefits involves proving you can’t work. We have the right to shop and eat at restaurants, but if we make enough money to lift ourselves out of poverty and have disposable income, we risk losing benefits. There are work programs and ways around some of this, but they add exhausting and time-consuming hoops we must jump through which ultimately impede our success.

Despite the ADA, people with disabilities still face ongoing employment discrimination. Enthusiastic human resources managers fall silent when we arrive at an interview with our mobility devices, and companies become hostile when we request accommodations for invisible conditions. Technological advances have made working from home possible in many circumstances, but far too many businesses refuse to allow it. (The Mighty, with our largely remote team composed of many people with disabilities and chronic illnesses, proves you can run a successful company with employees who in some cases have never even met in person.) People with disabilities are also the only group that can legally be paid under minimum wage. Thus far, attempts at repealing this portion of the Fair Labor Standards Act have failed and tens of thousands of people still labor in isolated “sheltered workshops,” often earning only pennies per hour. We’ll never achieve full equality while we can be paid less.

Future expansion of the ADA should also focus on securing our rights to live in the community. People with disabilities have a right to accessible housing, but if we can’t get the support services we require to live there independently, it might as well not exist at all. Too many people with disabilities are still trapped in nursing homes or in their parents’ homes on waiting lists for accessible housing and other services.

The fight for disability equality is inextricably linked to the fight for equitable healthcare. We cannot move beyond survival mode if we are constantly in fear of losing healthcare or being denied based on a pre-existing condition. We cannot advance in our careers if we must limit our income because Medicaid is the only form of healthcare that covers in-home personal care services such as help getting dressed and bathing. We cannot build strong families when Medicaid makes it impossible for us to get married. Last year’s fight to save Medicaid echoed the Capitol Crawl and demonstrates how essential — though still inadequate — Medicaid is for the disability community.

And finally, we must continue to advocate against stigma surrounding disabilities. We must reform the criminal justice system so people with mental health or intellectual disabilities, the vast majority of whom are non-violent, receive treatment and support instead of imprisonment. We must strengthen hate crime laws and do more to prevent people with disabilities from being abused by caregivers. The ADA promised us a voice — but we must continue to fight to ensure we are heard.

Photo credits: Wikipedia, Smithsonian, Tom Olin.