Aspire Hanley Middle School Apologizes After Teacher Limits Students to 2 Bathroom, Nurse Passes Per Month

Sometimes the news isn’t as straightforward as it’s made to seem. Jordan Davidson, The Mighty’s editorial director of news and lifestyle, explains what to keep in mind if you see this topic or similar stories in your newsfeed. This is The Mighty Takeaway.

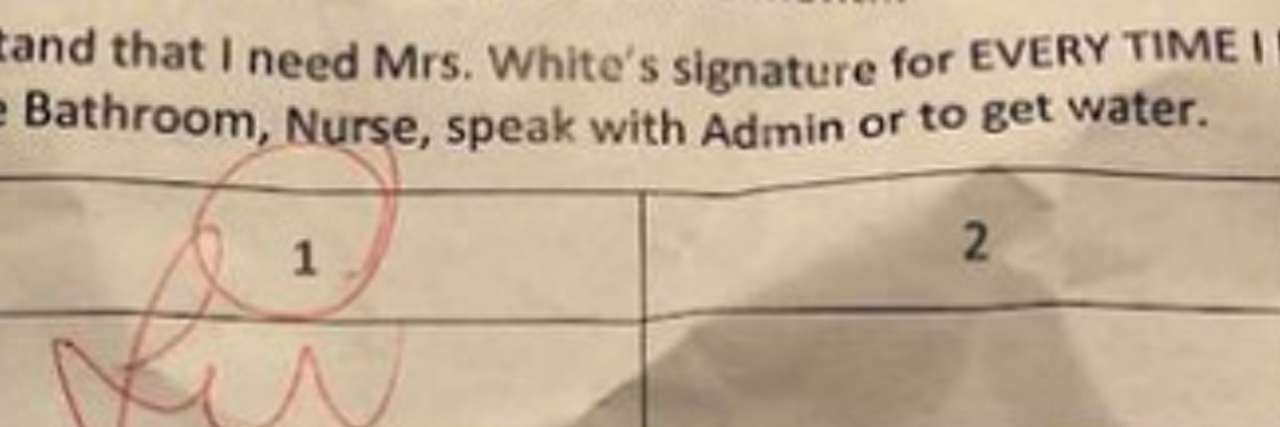

Aspire Hanley Middle School, a charter school in Memphis, Tenessee, is doing damage control after the hall pass a teacher issued to a student went viral on social media. The pass limits eighth-grade students in Mrs. White’s class to two water, bathroom, admin or nurse trips per month.

Your child comes home and shows you this note her teacher had her sign at school.

What’s your reaction? pic.twitter.com/x6hG3HepZJ

— ????international people can get horaries now (@iJaadee) August 30, 2018

To use the facilities or leave the classroom, students would need to have White sign the pass. Any further need after two uses would automatically result in detention. The only students exempt from the policy were those with a doctor’s note. The school issued a statement on Thursday, alerting parents that the policy is “inconsistent” with the school’s protocol and being investigated.

As people on social media pointed out, there are a lot of problems with creating a pass like this. It forces minors to sign contracts without an adult, violates students’ privacy and can be traumatizing or humiliating for students who need more than two trips to ask for help in such an unsupportive environment.

Responding to criticism, the school’s superintendent Dr. Nickalous Manning, told local news, “I think that students have the opportunity to see the nurse or use the restroom. They can make that request.”

It’s understandable that schools and teachers don’t want students running amuck in the hallways, but attitudes like Mrs. White’s are not uncommon. Kids who ask to use the bathroom more or need to visit the nurse frequently are often labeled “nuisances,” and that’s a problem.

When I was a kid, I used to get “stomach aches” a lot and was a frequent flier at the nurse’s office. Whether it was the teacher who begrudgingly sent me there or the nurse when I walked in, someone’s eyes would roll. I knew something was wrong, but since students often bullied me for being short, my physical symptoms were often brushed off as nerves. I never felt like I got adequate help for my symptoms or the bullying. The best I got was “OK, you can lay on the cot for 20 minutes.”

When I was 12, I was diagnosed with endometriosis, a reproductive health condition that causes inflammation, scarring and pain that usually reaches its peak around menstruation. A pass like Mrs. White’s would’ve landed me in detention every time I got my period. Assuming half of her class menstruates — the average age a person gets their period is 12, most eighth graders are between 13 and 14 years old — many students would be facing detention just for wanting to maintain personal hygiene.

Passes like this, eye rolls when a student asks to go to the bathroom frequently, disdain over the student who seems to hide out in the nurse’s office send a dangerous message to students who often just need help. By the time I got to high school, constantly being told I was exaggerating or feeling like I couldn’t talk openly about my condition because no one wants to hear about my “period problems” made me too ashamed to ask for help. When I was 16, I had a period that was the equivalent of hemorrhaging. I went to school during it, only leaving at one point because I had run out of pants to change into. After two weeks of bleeding, I ended up in the hospital where doctors recommended a blood transfusion to replace all the blood I had lost. When people asked why I waited so long to tell someone, why I didn’t go to the nurse and ask to go home sooner, I said it was because I was tired of the eye rolls, of not being believed. I didn’t want to hear, “Again, Jordan? You need to leave again?” So I stayed and was worse for it.

Policies like this don’t just hurt students who menstruate or have reproductive health conditions. It’s all kids who don’t fit what is deemed “normal” or “well-behaved.” A neurodiverse child may need to get up more than a neurotypical one. That kid who goes to the nurse a lot may have anxiety but doesn’t have the ability to link their racing thoughts to their stomach pain. At 10 years old, I couldn’t tell you my uterus hurt. I didn’t even know what a uterus was.

As adults, it’s time we believe kids and start treating “obnoxious” or “attention-seeking” behaviors as a sign that child has something to say, even if they can’t verbalize it. If a kid asks to leave the classroom a lot, ask them why in private. Engage the kid who is always in the nurse’s office in conversation. Ask how you can help beyond an ice pack or 20 minutes on the cot. Like adults, kids can get sick, have anxiety, depression, troubles at home — they just might not know how to tell you. Instead of demanding they limit or deny their needs, treat them with the decency and kindness we all deserve.

Header image via Twitter.