Dogs and Autism: A Match Made in Heaven

Editor's Note

This story has been published with permission from the author’s son.

Many parents raising children on the autism spectrum already know this: dogs are intuitive, empathetic and responsive to the needs of our children.

It shouldn’t come as a surprise then, to learn that many people on the spectrum list “petting my dog” as a calming strategy when asked to share their tips for coping with anxiety.

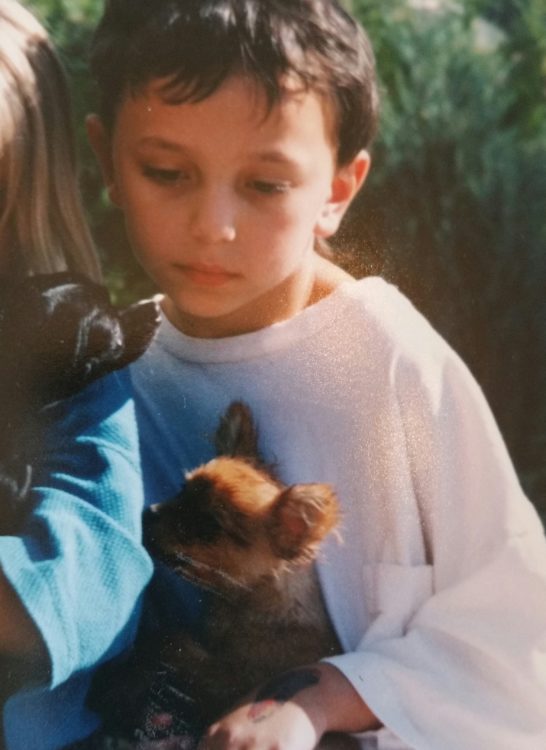

Brain was Daniel’s therapy dog. Well, he wasn’t a certified, professionally-trained therapy dog, but he was . . . well, let me explain. He was 5 whole pounds of Chihuahua attitude — not a yappy, snappy attitude, but a, “Hey meester. I’m a Cheewawa! You got cheese? I’ll do tricks for you! C’mon, c’mon, c’mon!” (Jump, jump, jump, jump, jump, jump).

Brain never sat still. He was a dog-in-motion at all times, and only stopped moving when it was his time to sleep. He loved to be petted and lived for tummy rubs, but unlike some dogs, he was definitely not a licker. His tongue stayed in his mouth (thank you very much, because his Chihuahua breath could peel pain off the wall). Gratuitous licking was for . . . well . . . dogs, and he thought he was a person, I think.

He loved to be around his humans. If we were sitting in the living room, he’d nudge us to lift him onto our laps, and then trot back and forth on the sofa, only occasionally and briefly pausing to make sure the cat knew that this lap — all laps, actually — belonged to him. He liked to try to speak as well; he made vocalizations that sounded like “Hello” that would have us doubled-up with laughter. He knew when to do this vocal trick, and would also do it on request. Alas, his talent predated the explosion of YouTube — he could have been a star, for sure.

Brainy typically stayed with Daniel at night, but he slept with me when my son was away. I use the word “sleep” broadly, because his little dog was the epitome of canine motion: walk to the top of the bed, find a pillow, circle the pillow. Naw. Too hard. Walk to the bottom of the bed. Play with the cat. Scamper to the top of the bed. Find another pillow (mine). Scratch at the pillow to find the sweet spot. Get gently moved off the pillow. Roll on his tiny back to show submission and win scratch, scratch, scratches that felt soooooo good.

Eventually he would settle under the covers or on the pillow beside my head.

I describe all of this to you because Brain was an entirely different animal if my son was feeling anxious — which, as is the case for many on the spectrum, happened all too often. Brain just seemed to know when something was wrong. As Daniel’s anxiety would rise, Brain would climb up onto his chest and lick my boy’s chin and cheeks. He would then splay himself across Daniel’s chest like a starfish, completely limp and still, and in doing so, make himself as heavy as his little body could be.

As he did this, Daniel, often inert with anxiety and staring blankly ahead, would raise his hand to Brain and Brain would lick my son’s arm, his wrist and the back of his hand. These scenarios played out for as long as it took for Daniel’s anxiety to abate. The warmth and love on Daniel’s chest seemed to stop the anxiety in its tracks: Brain was the sweetest, most loving weighted vest in the world. Our dog’s little body, and rhythmic in-out, in-out of his breathing, helped Daniel to focus on something other than his sense of dread, and to be mindful, in those moments, of the pure joy of this connectedness with his best friend.

Brain seemed to sense when Daniel began to emerge from his anxiety-state. This adorable Chihuahua would bounce to attention, and standing on all fours, go almost nose to nose with Daniel. It was as if he was examining my son’s face for signs of improvement. As soon as Daniel was back to himself, Brain was back as well. Jumping, running, prancing, preening and never, ever sitting still.

Brain wasn’t a trained therapy dog. He just loved Daniel and did all he could to help him. That help was the best serving of therapy a kid could hope for, and it came with a side order of love and friendship.

Daniel seemed to know when something was not right with Brain. One night about 10 years ago, Daniel called and asked if he could come home. It was mid-week and he was away at university. I made the long drive to get him and he couldn’t explain his need to be close. The night gave us clarity. Our beloved dog was gravely ill.

You could see Brain was terrified, and he struggled as end-stage congestive heart failure robbed him of air. His mouth stayed open, baring his teeth, and his eyes were wide with fear. The vet asked if I wanted to hold Brain while receiving an injection that would put him to sleep. I looked to Daniel and the vet understood, and placed Brain into Daniel’s arms. A wonderful thing happened. Brain’s gaping jaw relaxed and his gasps were less labored. His eyes were no longer wild with fear. His body relaxed as his human buddy circled him with love in his big warm arms. He looked up at Daniel. Daniel spoke to him, soft comforting words, and thanked him for being such a great friend. Brain looked at him and I swear to you, he seemed to understand.

There was no visible fear left in Brain when Daniel nodded to the vet that it was OK to give the shot. Almost immediately, Brain went to sleep.

I have been present at many passings in my life. I have seen grief and experienced loss. I have never seen the anguish that my son experienced that day. He really did lose his best friend in the whole world. It was not easy. Even now, memories are heavy on grief and light on whimsy.

We have other dogs now — two Chihuahuas and a chocolate lab named Buddy. Like Brain, Buddy comforts Daniel, and is ever-so-patient when Daniel needs a hug, or to simply pet him for an hour or two. All of the dogs honor Daniel’s need to be close to them. Daniel loves dogs. Dogs love Daniel.

The loss of Brain was devastating, of course, but his presence in our lives changed things for the better. Daniel learned about loyalty, friendship and putting the needs of others before his own in a way that no social skills program or emotions training could ever do.