For Young People: What to Know if You Self-Harm

Editor's Note

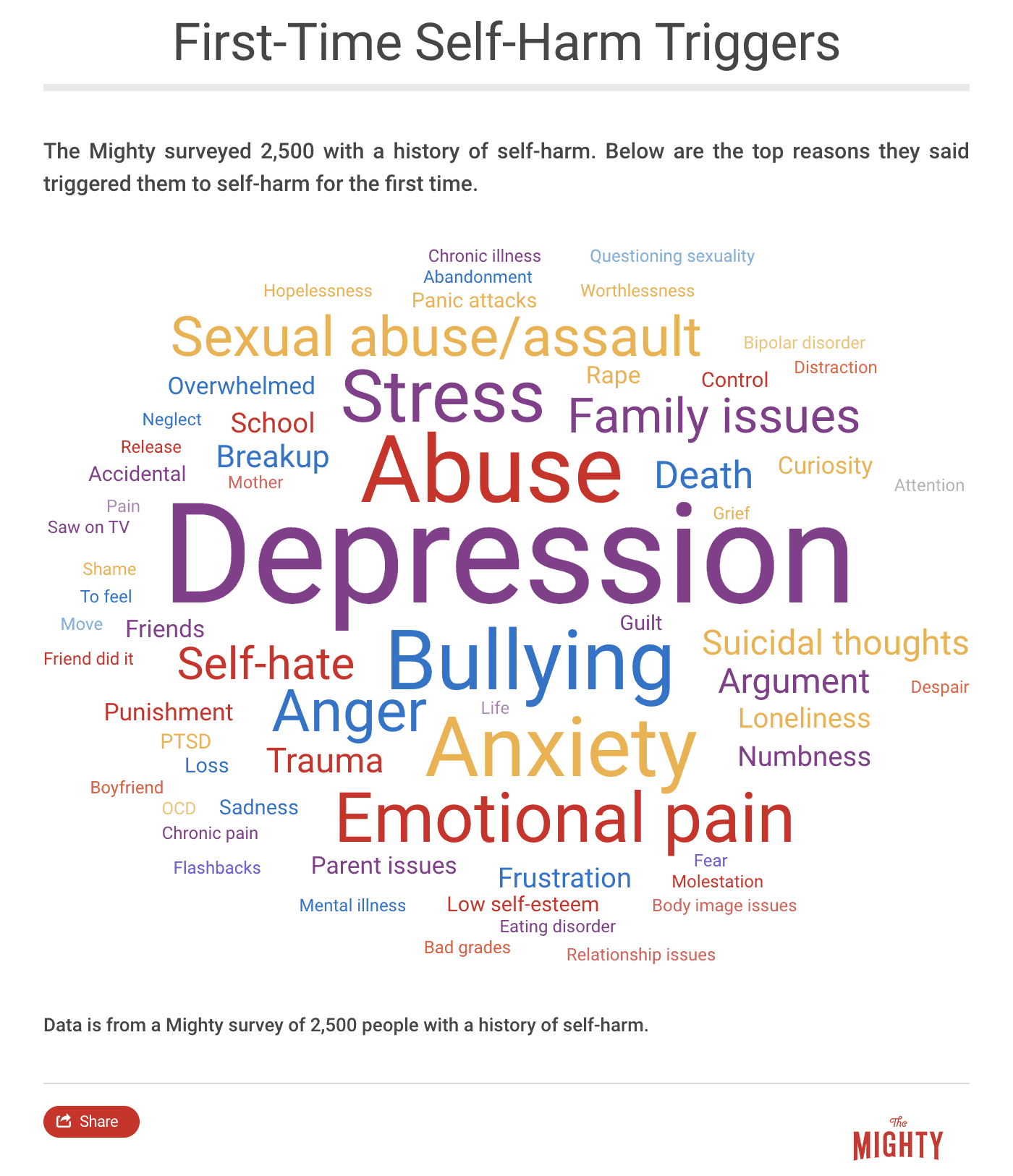

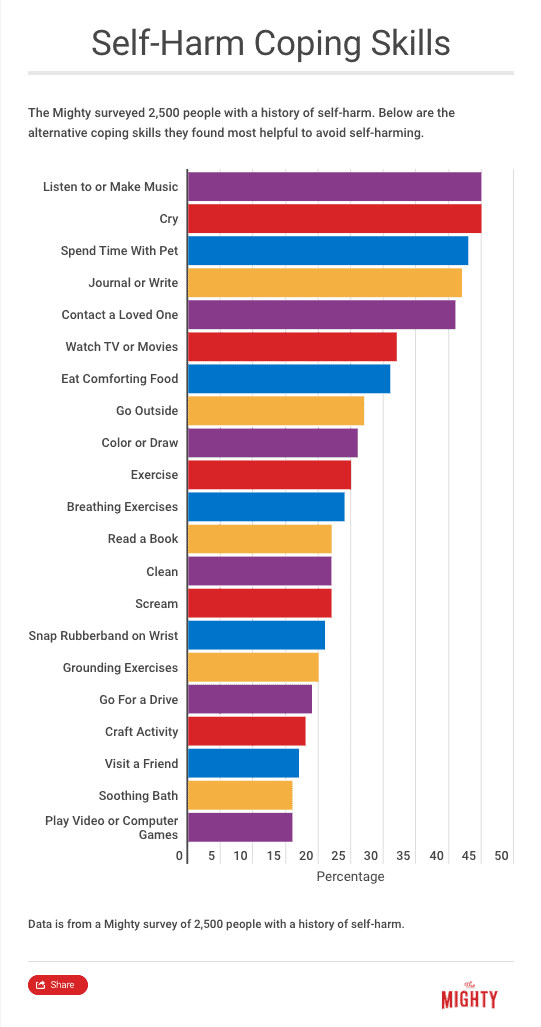

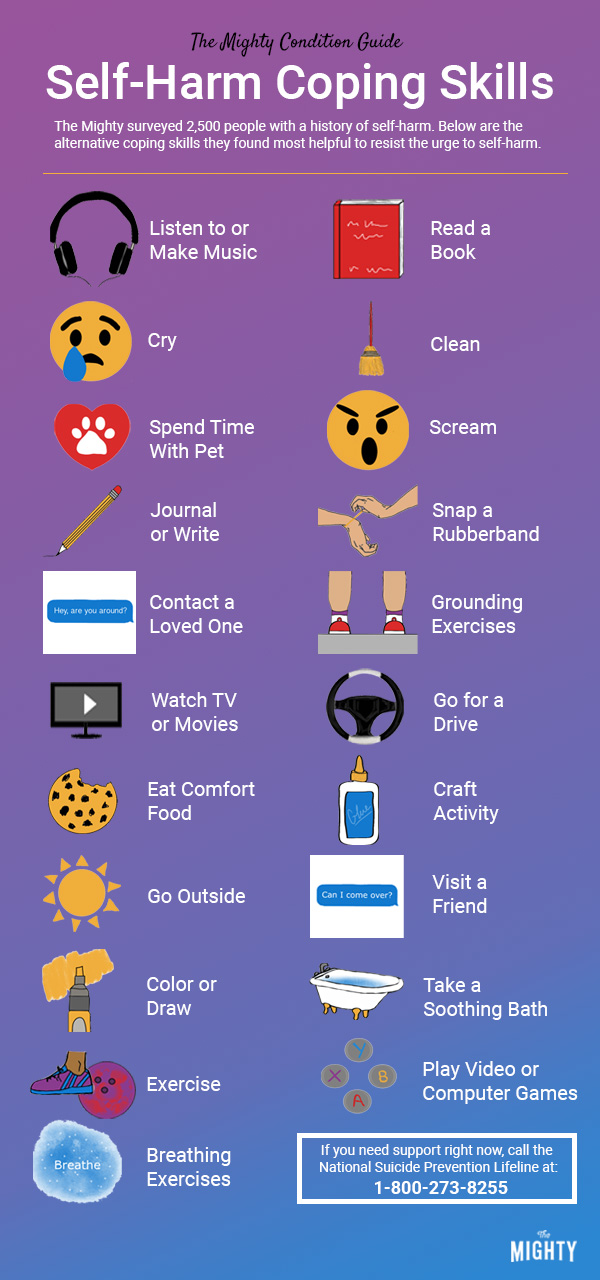

The Mighty’s Condition Guides combine the expertise of both the medical and patient community to help you and your loved ones on your health journeys. For the self-harm recovery guide, we interviewed four mental health experts, read numerous studies and surveyed 2,500 people with a history of self-harm. The guides are living documents and will be updated with new information as it becomes available.

Why Do I Self-Harm?

Self-harm can make people feel better, especially when you’re really having a hard time and your emotions were too big or you felt empty. But in the long run, it’s not a safe way to cope with what you’re feeling. With support from people you trust and new coping skills, you can learn to manage the hard stuff without self-harm.

Learn More About Self-Harm Recovery: Overview | For Adults | For Parents and Loved Ones | Resources

Medically reviewed by Joanna R. Stern, Psy.D. at the Child Mind Institute

How to Ask for Help | Coping Skills | Recovery From Self-Harm | What to Know About Scars | Do You Need Medical Attention? | How to Get Help In a Crisis

For Young People: What to Know if You Self-Harm

If you self-harm, whether you’re 12 years old or 24, you might feel pretty alone. Maybe you heard your parents or other kids talk about how “weird” self-harm is. Or how they “can’t believe someone would do that to themselves.” Or even, “They’re just doing it for attention.” None of these statements feel very good. Here’s some news for you: They don’t understand what they’re talking about.

Self-harm can make people feel better. It may have helped you feel calm when your emotions were too big or when you felt totally numb or empty. Maybe you’re under too much pressure to do well in school and to be happy all the time. Meanwhile, nobody knows how much you hurt inside. You self-harm to manage everything you feel but can’t talk about. Self-injury can feel like your best friend. But in the long run, it’s not a sustainable or safe way to cope with what you’re feeling.

Anybody might self-harm. You could get straight As and be the best player on your soccer team. You might wear black combat boots and dark makeup. You could have any gender identity, race or sexual orientation. You could have a mental health condition, though not everyone who self-harms has a diagnosis. Just because you self-harm doesn’t mean you automatically get diagnosed with a mental health condition.

In the long run, it’s usually best to learn new skills to deal with the hard stuff. That could be coping skills to calm down intense emotions or learning to deal with anger, sadness or anxiety in a more effective way. If you’ve survived hard experiences, you might learn how to turn down the intensity of the feelings you have about the situation. Maybe you learn how to reach out for help from your parents or a therapist.

It is possible to stop self-harming. Though it might be a hard journey that takes work, you can recover and find new ways to cope.

How to Ask for Help

Reaching out for help for self-harm is an important step to feeling better. Everyone who self-harms needs extra support. Self-harm isn’t an easy topic to bring up. You may feel nervous even thinking about telling someone else about. Talking about self-harm is a brave thing to do.

You also have to decide who to tell who can get you the support you need to recover. Who can you tell that will react in a supportive way? Who can you trust? What will they say? Who else will they tell? You might not feel comfortable talking to your parents right away. You might be afraid a school counselor will tell your parents before you’re ready.

Should I Tell My Friends?

It’s totally normal you’d want to tell your friends about self-harm. They get you better than anybody else. There isn’t necessarily a right or wrong answer about telling your friends, but here’s what you should consider. Learning that you self-harm can be hard for your friends.6 Friends might promise they won’t tell anyone else. This probably sounds like a good idea. But it’s not always in your best interest. It’s also a lot of pressure. Your friends may not know what to do to support you. Not because they don’t care but because it’s hard to know how to help. It’s not that your friends can’t be supportive, but adults may have more tools and resources to make sure you get the best support possible.

Who Should I Tell?

When you’re ready to tell someone about self-harm, reach out to an adult you can count on. Talking about self-harm will probably feel uncomfortable. It might seem easier not to bring it up to an adult at all. But a trusted adult can help you in a lot of good ways. For example, they can ask questions, help you find resources like a therapist or support you when you decide to tell your parents.

Your parents or primary caregivers could be a great place to start. If you don’t feel like you can talk to your parents or guardians, find another adult you can trust.6, 11 This could be an aunt, your favorite teacher, a neighbor, an older brother or sister or your therapist if you have one. You can also try your school guidance counselor. Keep in mind that a guidance counselor might be required to tell your parents right away because of school rules.5

How to Tell Your Parents

Talking to your parents or guardians about self-harm might be one of the hardest things to do. You don’t want to get in trouble or make them upset. Maybe they’re part of the reason you started self-harming in the first place. But if you’re under age 18, you’ll probably need to tell them. Why? Believe it or not, research shows that parents/caregivers play a huge role in the healing process.11

When you’re ready to tell your parents, consider the timing. Make sure you’ll have enough time to have a conversation. This means probably not when they drop you off for school.6 Try to have the conversation in a private place. Not your favorite coffee shop, for example, but at home at the kitchen table or during a long, quiet side-by-side activity like riding together in a car. It’s important to find what will work for you.

Think about what you want to say.3 You might want to write it out first or practice the conversation with a friend. Consider what questions your parents might ask so you can think about answers ahead of time. They might want to know, “How long has this been going on?” “Why are you self-harming?” “What can we do to help?” Being prepared can help you feel less nervous.

Also prepare yourself for what might happen after the conversation, such as the possibility talking to your parents doesn’t go the way you want it to and you feel upset or unsupported.3 If your parents react in a way that isn’t what you hoped for or need, you may experience the same strong, intense emotions that have led you to self-harm in the past and feel the urge to self-harm now. Plan ahead with ways to cope with these emotions so you are less tempted to revert to self-harm to manage the emotions after the conversation.

Think about what activities or other people can provide you with short-term distraction until the intensity of the emotions pass. How can you get support if your parents react badly? Who can you call? Can you visit another family member or a friend’s house? Are there TV shows, movies or music that help you calm down? If your parents don’t understand, can you have them call a trusted adult who does know about self-harm? It’s possible that the conversation will be everything you hope for and you won’t have to rely on these plans. But just in case, think through how you can take care of yourself too.

What to Expect From Your Parents

Parents might feel a mix of emotions when you tell them about self-harm. It’s not so easy to stay calm sometimes. However, your parents are the adults, and ideally, they shouldn’t take their own emotions out on you. You didn’t do anything wrong. Adults are responsible for their own actions, reactions and feelings. They shouldn’t ask you to make them feel better. If your parents are struggling, suggest they check out the parents’ section of this guide or ask them to talk to another adult.

An honest conversation about self-harm can be good for you and your parents. That doesn’t mean it won’t be hard. When you share your feelings, your parents might actually be relieved. Oftentimes parents suspect something is wrong but they don’t know exactly what. When parents know what’s wrong, they feel like they can actually help. It’s a brave step to reveal such a big part of yourself, especially when you don’t know how it might turn out.3 Celebrate your courage, no matter what happens.

What to Expect When You Tell a Therapist About Self-Harm

It is a good idea to find a therapist who can help you find other ways to deal with the hard stuff besides self-harm. A therapist lets you talk about what you’re thinking and feeling and helps you work through it, teaching you how to use effective coping skills to help manage strong emotions. Whatever you say to your therapist should be kept confidential or private unless they think you’re at serious risk for suicide or hurting someone else.

This might be a little different when you’re under age 18 because your caregivers are your legal guardians until you turn 18. What does this mean if you tell your therapist about self-harm and don’t want your parents to know? Will they have to tell your parents? Will your therapist tell your parents everything you say during your appointment? These are good questions because every therapist is a little different.

Ask your therapist directly: “If I were to tell you something about self-injury, what would you do?”11 This way you’ll know what to expect. Many therapists won’t tell your parents what you talk about, even self-harm. Or they might give a brief overview but not any details. Ask your therapist up front how they will handle this too.

Your therapist will probably encourage you to tell your parents about the self-harm.4 They will help you find a good way to do this and be there for you before and after. Know that if your self-harm gets very dangerous, your therapist will have to tell your parents. Therapists are legally required to do this.

Self-Harm, Therapists and the Hospital

In the old days, therapists often sent those who self-injured immediately to the hospital. This doesn’t happen so much anymore. Competent professionals now know most self-injury isn’t life-threatening. Their first reaction to self-harm isn’t to send you to the hospital right away. or to label you as “crazy.”

However, some states and some therapists still have out-of-date information. This means a therapist might try to hospitalize you for self-harm that isn’t life-threatening.5 Just because you self-injure doesn’t mean you will definitely be sent to the hospital. Ask your therapist ahead of time when they would decide to send you to the hospital. Don’t be afraid to ask. You have a right to know what your therapist will do or what they are legally required to do.

What Happens If Somebody Finds Out Before You’re Ready?

Telling someone about self-harm isn’t easy. It might take time to be ready to talk about it. You might want a plan first. But somebody could find out about the self-harm before you’re ready. Maybe your sleeve slid up in class and your teacher saw some scars by accident. Or your little brother barged into your room and found a box with your self-harm tools and bandages that he showed to your parents.

If this happens, do the best you can. Explain the self-harm as best you can. Answer questions as best you can. Show them this guide so they understand better. Remember, you didn’t do anything wrong. It’s a stressful situation that will feel like it makes everything worse. It won’t feel like this at the time, but people who are “outed” about self-injury generally said it turns out OK in the long-run.3

Going Online

Sometimes when you self-harm, you might pull away from friends and family because you don’t know what else to do.4 Sometimes it’s easier to find people who understand what you’re going through on the internet or social media. Your online friends might become your best support people.6 You can read other people’s stories and find out how they got better. However, not everyone online has your best interests in mind.

Some websites post graphic images or instructions, which might trigger a strong urge to self-harm.6 Cyberbullies also lurk online. They can say some pretty mean stuff that will probably make you feel worse. Other sites might suggest you can never find other ways to cope and self-harm will be a lifelong problem. That’s just not true.6 Proceed carefully when you’re online. Ask your therapist or even your parents for good self-harm resources on the internet. The resources section of this guide also has some pretty safe places to check out.

Ways to Self-Harm

If you’re searching online for ways to self-harm, try waiting out the urge by distracting yourself — play with a pet, call a friend, write in your journal, go for a walk, watch a TV show. If you need support right now, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 or reach the Crisis Text Line by texting “START” to 741741.

What Are Reasons Not to Self-Harm?

If you’re struggling and need reasons not to self-harm, try alternative coping skills (like journaling, taking a walk or calling a friend). You’ll find the urge (and intense emotions that come with it) will pass and you’ll start to feel better. Talk with an adult you trust, like a parent or therapist, who can also help when you’re struggling.

Coping Skills

When self-harm has been your go-to way to handle big feelings for a long time, giving it up might sound scary or even impossible.6 How else are you supposed to handle strong feelings? That’s where coping skills come in. Coping skills are alternative activities you can do to feel better and resist the urge to self-harm. They could include everything from coloring to going for a run, listening to music, calling a friend or meditation.

Using coping skills won’t be the same as self-harm. At first, it will probably feel like they don’t work at all. Self-harm might have gotten rid of the difficult feelings right away. Coping skills will take seconds or minutes longer, which can feel intolerable until you get used to it. But stick with it. Over time you can learn to use skills other than self-harm when you’re struggling.

Coping Skills You Can Try

You’ll want to find coping skills that work for you. They may be different depending on how you’re feeling. You might find it more effective to go for a run when you’re angry. When you’re sad, it could help more to listen to your favorite music. You’ll need a whole list of coping skills so you have lots of options when the urge to self-harm strikes. Experiment and find what you like the best.

Here are the coping skills that helped 2,500 people with a history of self-harm most:

You can also find other ideas here:

- Distraction Techniques and Alternative Coping Strategies (Cornell Research Program on Self-Injury and Recovery)

- A Guide to Coping with Urges (Self-Injury Outreach & Support)

- A Guide to Coping Day-to-Day (Self-Injury Outreach & Support)

- 146 Things to Do Besides Self Harm (Adolescent Self Injury Foundation)

Using a Code Word

Even if you make the decision to reach out for help, it may be difficult to know what words to use or to explain what’s going on. One idea to help with this is to have a code word.4 With your parents or another adult you trust, come up with a code word to use when you want to self-harm. Pick something easy to remember that won’t be confusing. For example, “dog” is probably not the best choice if you actually have a dog. You could choose another animal like “porcupine” or “octopus” or the name of your favorite movie character like “Hermione.”

Then decide how you want your support person to respond when you say the code word. Maybe you want the person to sit down with you so you can talk about what’s bothering you. Maybe you want to just talk about your favorite movie. Maybe you’d like a hug and don’t want to talk at all. Maybe you’d like to sit next to your support person in silence on the couch and watch TV. It might feel weird at first. As you get used to using your code word, it will get easier.

Creating a Safe Environment

When you’re ready, remove as many self-harm tools from your house as possible. It’s easier to resist the temptation to self-harm if you don’t have access to your tools.4 Enlist your parents for help. Ask your therapist about this too. Sometimes you can give these items directly to your therapist. By creating a safe environment, it’s easier to set yourself up for success because it’s not as easy to self-harm immediately.

Recovery From Self-Harm

Finding new ways to cope so you can stop self-harming is possible. It’s also a process and everybody’s journey will look different.4 Maybe somebody like your parents demanded you stop. That won’t work. It’s not that easy to stop. It’s too much pressure and it sets you up to fail. None of this will happen overnight. You will need support around you throughout the process. You — and especially the adults around you — need realistic expectations about what to expect.6

There are basically two parts to reducing and eventually stopping self-harm. Part one is learning to tolerate being uncomfortable without “fixing” it right away with self-injury. These are your coping skills and learning to “ride the wave” of self-harm urges. You may have urges even after you’ve stopped self-injuring.6 The goal is not to act on those urges.

The other important part of recovering is addressing why you self-harm.5 You want to look at why you self-harm with a therapist or other trusted adult. What’s happening right now in your life? How does it make you feel? Could you have a mental health condition that’s making things harder? You can heal the reasons you self-injure.5 Then you won’t need it anymore.

Behavior change isn’t linear. You may have another episode of self-harm after six months without self-injury. This doesn’t mean all of your hard work has failed — you’re not back at square one.4 After a self-harm episode that occurs after a period without self-harm, use the support of your therapist or a trusted adult to reflect on the skills that got you through six months and what triggered the most recent episode. Celebrate the hard work it took to get to that point and keep moving forward armed with new information. Recognize that it takes time to learn how to smooth out your emotions without self-harm. Take your time and reach out for support when you need it.

How to Find a Therapist

To reduce your need for self-harm, it can be helpful to work with a trained therapist. They can teach you new ways to manage emotions, help you find effective coping skills and sort out your reasons for self-harm. If it turns out you have a mental health condition, they can help you with that too.

When you’re looking for a therapist, try to find out about their experience with self-harm. There are a lot of therapists out there. Not all of them understand or specialize in working with people who self-injure.10 Ask your parents or an adult you trust for assistance. If you have health insurance, you can search for therapists who are covered by insurance. Call the National Alliance on Mental Illness helpline at 1-800-950-NAMI (6264) for other options in your area.

You can also search for counselors in your area using the searches on these websites:

What to Expect in Therapy

When you work with a therapist, it’s important that you feel safe and comfortable with them. Your parents might want to talk to your new therapist before scheduling an appointment. Most offer free, short phone consultations. Ask if you can speak with the therapist for a few minutes, too. This will give you a first impression. Do they sound nice on the phone? You can ask a few questions too and see how it feels. Quiz them a little on their knowledge about self-harm.

If you’re uncomfortable after talking with them, try another therapist. At any point during therapy if you realize your therapist isn’t a good fit, don’t be afraid to speak up. No matter if it’s your first appointment or your 10th. Talk to your therapist. Talk to your parents or another adult. It’s easier to focus on hard topics when you’re with someone you trust. Your therapist should validate what you’re feeling and not make you feel like a bad person because of the self-harm.

A therapist is a neutral person — they’re not your parents. You can tell them almost anything without getting in trouble. Therapists are required to follow strict confidentiality guidelines. Unless they think you’re at risk for suicide or hurting someone else, what you say to your therapist should be kept confidential and private. If you’re unsure about this, ask your therapist. Good therapists will let you know what their rules are.

Dialectical Behavioral Therapy

One type of therapy that’s known to be highly effective in helping you reduce self-harm is dialectical behavior therapy (DBT).7 One study, for example, found that for every two months of participation in DBT, people were able to reduce their self-harm by 9 percent.9 DBT was originally developed in the 1980s with those who lived with self-harm, suicidal thoughts and borderline personality disorder (BPD) in mind. However, DBT has since been shown to be effective for many other mental health conditions, including depression, anxiety, eating disorders and substance use.

DBT teaches skills that are organized into the following four modules:2

- Mindfulness

- Distress tolerance

- Emotional regulation

- Interpersonal effectiveness

If you work with a DBT therapist, they might also work with you and your family on a fifth set of skills called Walking the Middle Path to help you communicate better with your parents so you both understand what’s going on.2 All the DBT skills are designed to help you tolerate big feelings effectively without self-harming, learn how to make decisions that help you balance emotional and rational thinking and help you more effectively interact with others.

You learn valuable skills like:

- Mindfulness, which helps you be in the present moment and focus on one thing at a time

- Radical acceptance, which helps you to tolerate the distress of unpleasant circumstances that you can’t change right away

- How to “ride the wave” of a strong emotion without acting on it

- How to ask for what you want or say no effectively

For young people and families participating in DBT skills groups, you will also learn skills like dialectical thinking, or how to understand and appreciate both perspectives in a given situation. DBT teaches you to approach your thoughts and emotions from a non-judgmental stance, which can be extremely important in learning to reduce self-harm and understanding the non-linear nature of progress.2

A full DBT program includes weekly sessions with an individual therapist, access to a therapist to provide real-time coaching in skills use outside of sessions (usually offered 24/7) and a weekly skills training group with other people experiencing similar things. Some therapists will offer treatment that incorporates aspects of the DBT skills described or even a skills training group you can join without participating in a full DBT program (particularly if you already work with another therapist you feel comfortable with).

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

Another therapy that is sometimes used to decrease self-harm is cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) because it focuses on changing your thoughts, emotions and behaviors. CBT therapists will help you examine what happens for you in the moment when you feel the need to self-harm and brainstorm strategies to cope with self-harm urges in a more effective way.

Other Types of Therapy

There are hundreds of types of therapy, from talk therapy to DBT and CBT. While DBT and CBT are two of the most recommended types of therapy for reducing self-injury, sometimes it’s hard to find a therapist who uses these skills near you. When you’re looking for a therapist, ask what types of therapy they are trained in, because often therapists know several different kinds of skills or ways of working with people, including DBT or CBT skills. If you can’t find a therapist who knows DBT or CBT skills in your area, look for someone who has experience treating self-harm and who makes you feel comfortable enough to open up.

Group Therapy for Self-Harm

There aren’t many therapy groups specifically for self-injury and they’re hard to find. This is partly because some people believe self-harm is contagious. In other words, if you hear someone else talking about self-harm, you might self-injure even more. If you’re looking for group therapy, consider a DBT skills group, which will help you learn effective, new skills for reducing self-harm.

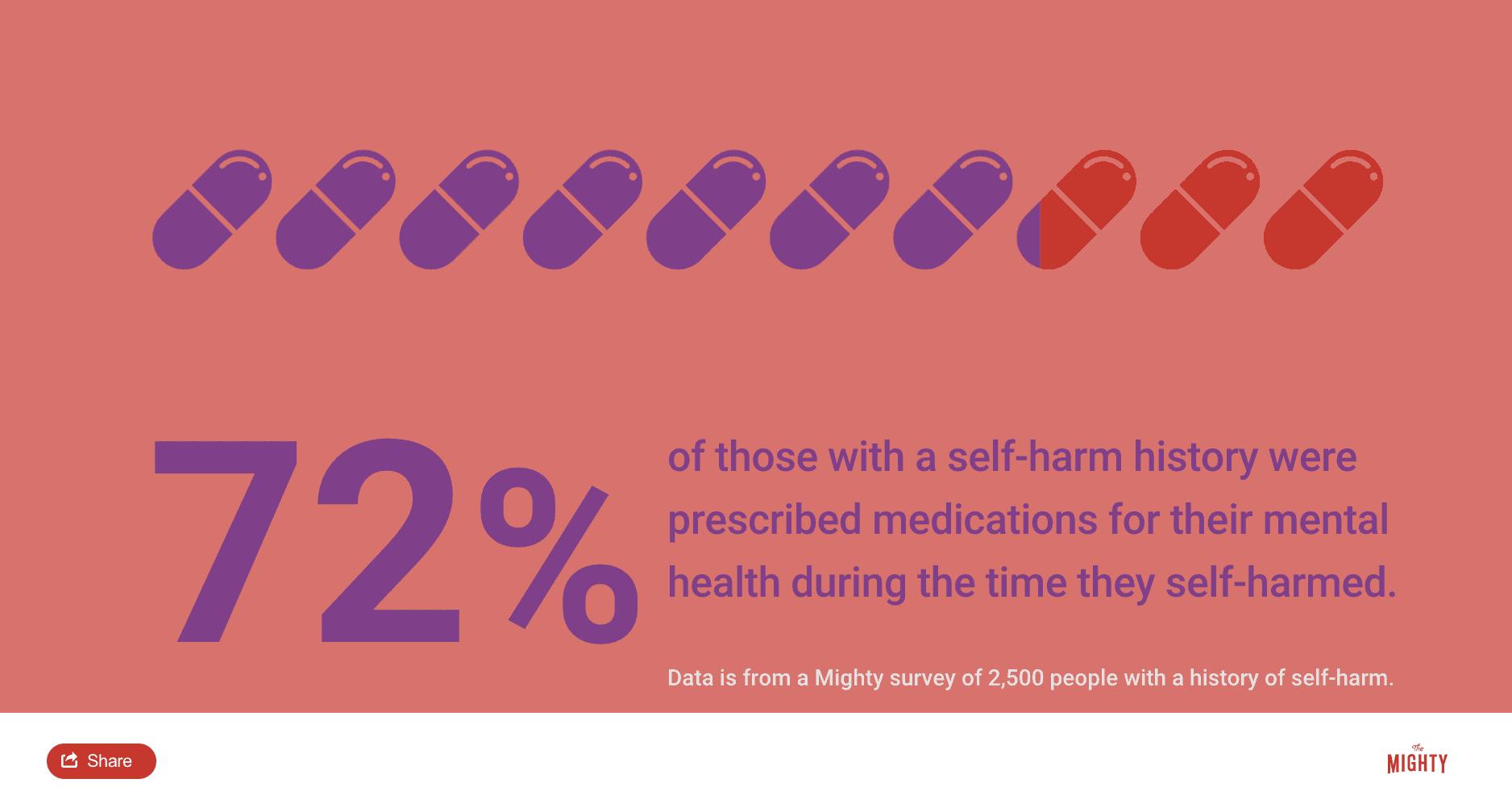

Medication

Sometimes you might need medication, especially if you live with a mental health condition. Medication can make it easier to manage big feelings. When you’re depressed, for example, you might feel so low no matter how many coping skills you try. Medication won’t fix everything. But in some cases, it can balance your moods enough that it’s easier to use coping skills other than self-harm. It also gives you more energy to work on what you’re having trouble with in therapy.

If you need medication, you’ll probably be referred to a psychiatrist. A psychiatrist is a doctor who specializes in mental health and can prescribe you medication. Family doctors can also prescribe mental health medications. Psychiatrists just have more practice with mental health conditions, feelings and moods, and self-harm.

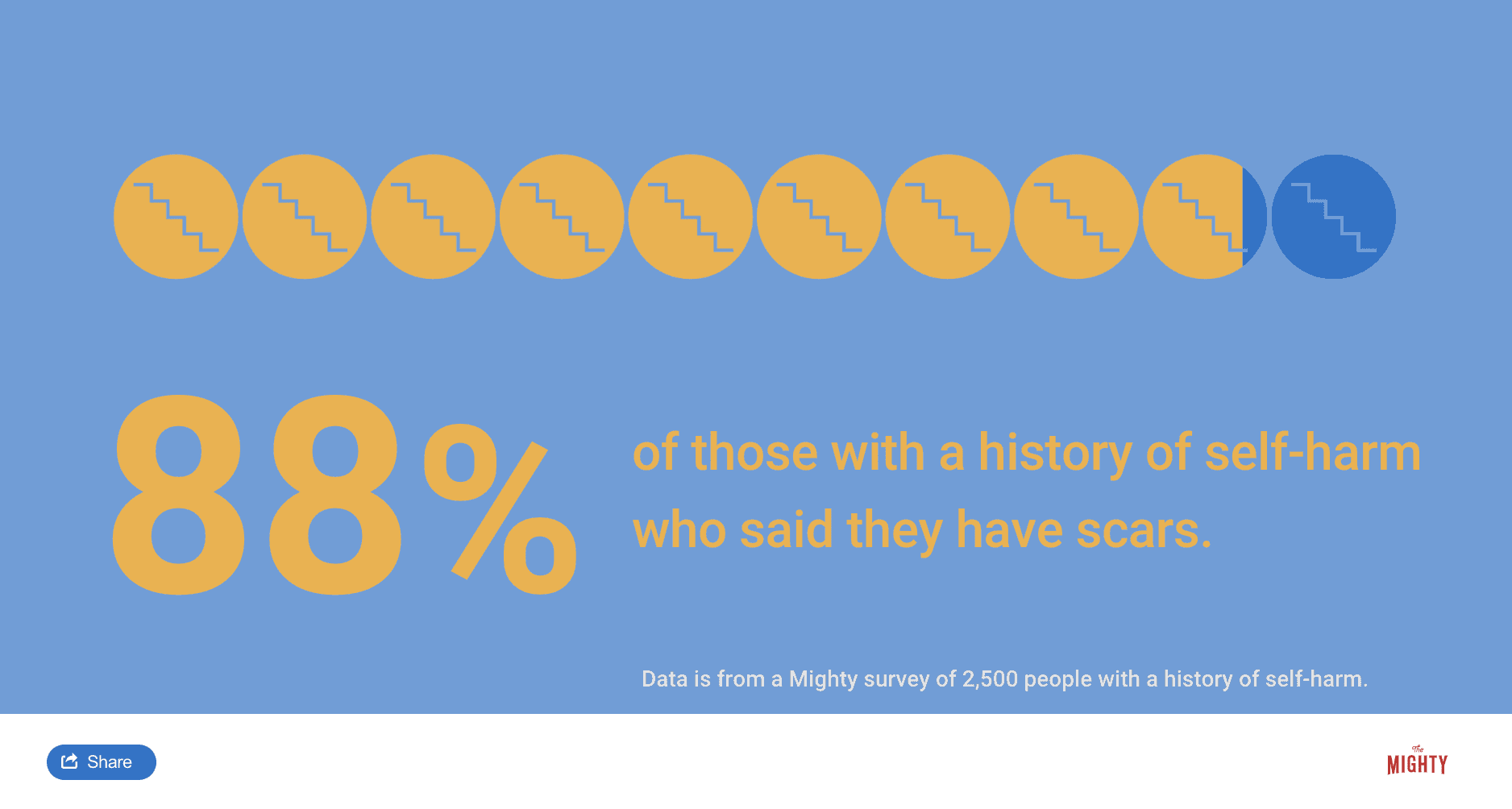

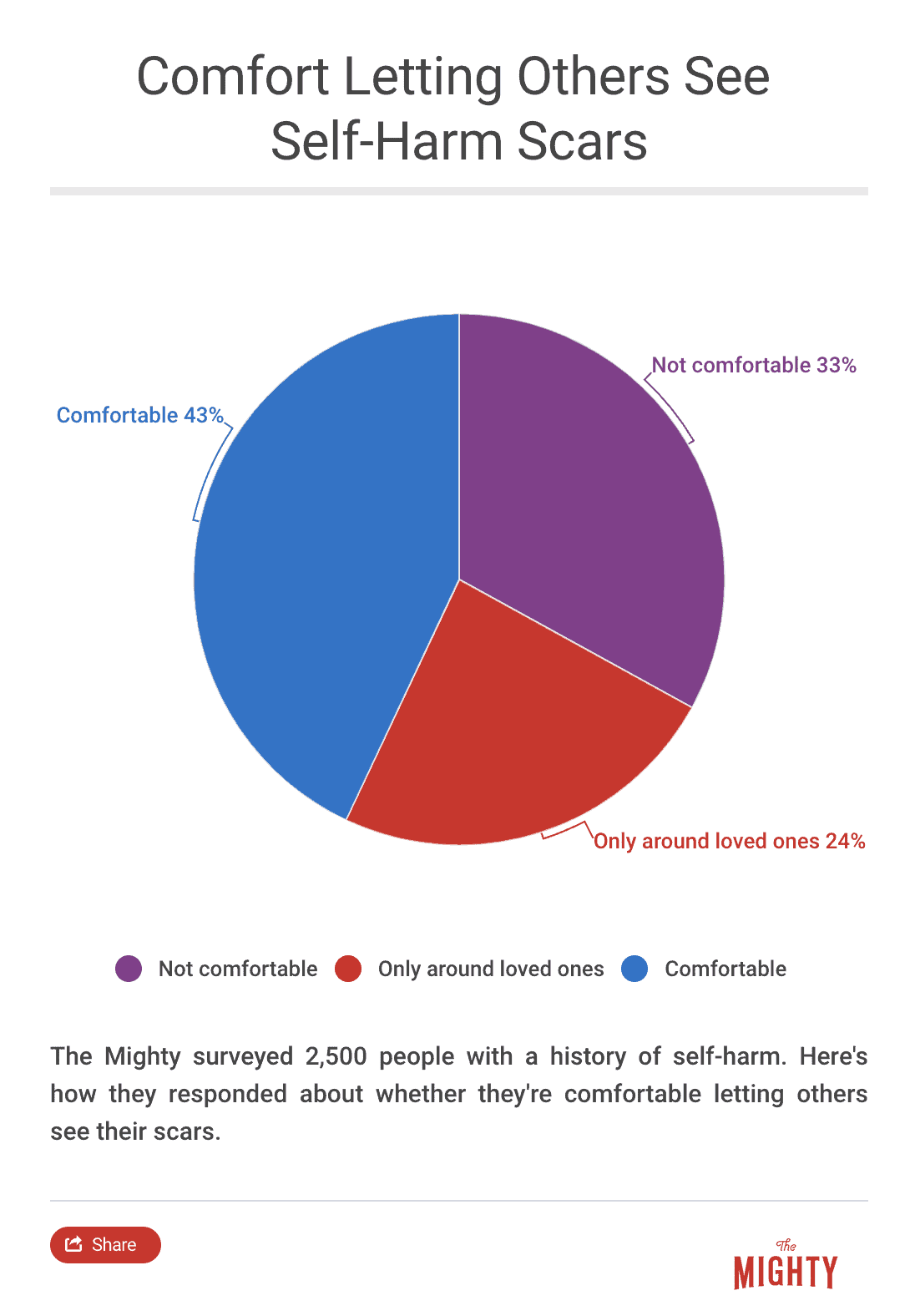

What to Know About Scars

With other mental health conditions, you can’t usually tell just by looking at someone what they have struggled with.6 You won’t know they had depression in the past based on their physical appearance, for example. Self-harm is often different. You may have physical scars. Some of them may be very obvious, even if you keep them hidden under your clothing.

Everybody views their scars differently.6 You could hate having scars because they’re a constant reminder of what happened in the past. Or you could feel like your scars prevent you from moving forward. On the other hand, you might also view your scars as a sign of strength. They show how much you have overcome. You survived, and your scars are proof. Part of reducing self-harm in the long-term includes finding some self-acceptance about your scars.6

Answering Questions

Be prepared for someone to ask about your scars. Adults might want to know out of concern for you. Friends and younger people might be curious. People don’t always realize what they’re asking when they point to your scars. Explaining self-harm isn’t simple and it can be painful. You don’t always want to give away your whole history. A lot of people will deflect and say they got scratched by their cat or fell off their bike. Having an idea of how to respond if people ask can be helpful so you’re not caught off guard.

When young kids ask about scars, they’re usually just curious. You can simply explain that they’re scars and ask if they have any.7 For friends or adults, try politely but confidently closing the question. Try responses like, “Thanks for asking, but that’s not a story I am willing to share right now.”7 Or, “I appreciate the concern. My scars represent a hard time from my past.” An adult might not accept these responses. In that case, ask if you can have the conversation at a different time when you feel more prepared.

Self-Harm Tattoos

Some people have found tattoos to be a powerful way to honor their past with self-harm. Tattoos can be a visual reminder of your survival.9 They can also cover self-harm scars with meaningful artwork or phrases that have meaning to you.8 To get a tattoo on your own, you have to be at least 18 years old. That doesn’t mean you can’t plan the artwork ahead of time, which can double as a coping skill. If this is something you really want to do, you could even ask your parents about getting a tattoo sooner by explaining how positive they can be.

Looking for self-harm tattoos? Check out some of these articles others have found helpful:

- 28 Tattoos That Give Us Hope for Self-Harm Recovery

- 28 Tattoos That Cover Self-Harm Scars

- How Tattoos Are Helping Me Recover From Self-Harm

- What Getting Tattoos Means to Someone With a History of Self-Harm

Scar Treatments

Scars are the result of your body’s natural way to heal itself after a wound. There are different types of scars. Some are small and may disappear over time. Others are big or even raised and very visible. If you care for your wounds effectively, it can help reduce the scars that form in the first place.1 You can also look into scar treatments to make your scars less visible. To learn about your options, talk with your family doctor or a dermatologist, a doctor who specializes in skin. They will be able to recommend potential scar treatments that will be safe and most helpful based on the type of scars you have.1

Do You Need Medical Attention?

It’s important to take care of your self-harm wounds. The best person to ask about wound care is a doctor. Depending on the wound, it might need to be cleaned, covered and treated with a cream at home. You might need treatment at a doctor’s office or hospital. Sometimes wounds should be treated with prescription creams or you might need additional care. Taking care of your wounds lowers your risk of infection and worse injuries.

If your wounds are serious or you’re not sure, you may need medical help. Talking to a doctor — or anyone — about self-harm wounds might not be easy. Sometimes the only way to get to the doctor might be to tell your parents, which might be something you don’t want to do. Regardless, if medical care is required, it’s really important to go to the doctor. You don’t want to get an infection or deal with worse injuries later.

Similar to coping ahead of time with how to have other conversations, it’s helpful to think through a plan in advance for how to get medical care if needed. Ask your therapist or psychiatrist if they know any doctors who understand and will be more sensitive to self-harm. Don’t be afraid to ask questions of your doctor ahead of time about what they know about self-harm and how they would handle a self-inflicted wound. Enlist your parents for help if you can. By having a plan in advance, it takes some of the stress out of doing this an emergency. Plus, you’re more likely to get help if you have information in advance and know what to expect from your doctor.

How to Get Help in a Crisis

This might not be your intent most of the time, but you are at higher risk for suicidal thoughts if you self-harm. If you feel totally overwhelmed and feel like you don’t want to be alive anymore, or you find yourself making plans to die, reach out for help immediately. You are valuable and important. You’re not alone. Find your parents or call another trusted adult if you can. You can also call or text the following numbers to get help:

If you are feeling suicidal, there is hope.

- You can call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline 24/7 at 1-800-273-8255

- You can reach the Crisis Text Line 24/7 by texting “START” to 741-741

- You can call The Trevor Project, an LGBT crisis intervention and suicide prevention hotline, 24/7 at 1-866-488-7386

If you are hard of hearing, you can chat with a Lifeline counselor 24/7 by clicking the Chat button on this page, or you can contact the Lifeline via TTY by dialing 800-799-4889.

To speak to a crisis counselor in Spanish, call 1-888-628-9454.

Head here for a list of crisis centers around the world.

For additional resources, see the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention and SAVE (Suicide Awareness Voices of Education).

You can read the following stories from people who’ve been there:

- If You Feel Like You’re ‘Losing’ to Your Mental Illness, This Is Your Reason to Stay

- For When Your Only Thought Is Suicide

- The Difference Between Wanting to Die and Wanting the Pain to Stop

- Dear Suicidal You

And for additional messages of hope, click here.

You are not alone.

Learn More About Self-Harm Recovery: Overview | For Adults | For Parents and Loved Ones | Resources

Sources

- American Academy of Dermatology. (n.d.). Scars: Overview. Retrieved from https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/bumps-and-growths/scars

- Behavioral Tech. (n.d.). What is Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT)? Retrieved from https://behavioraltech.org/resources/faqs/dialectical-behavior-therapy-dbt/

- Ernhout, C., & Whitlock, J. (2014). Reaching Out For Help: Talking About Ongoing Self-Injury. Retrieved from http://www.selfinjury.bctr.cornell.edu/perch/resources/reaching-out-for-help-pm-5.pdf

- Goodman, J. (2018). Self-injury [Telephone interview].

- Lader, W. (2018). Self-injury [Telephone interview].

- Lewis, S. (2018). Self-injury [Telephone interview].

- Rothenberg, P., & Whitlock, J. (2013). Wounds heal, but scars remain: Responding when someone notices and asks about your past self-injury. Retrieved from http://www.selfinjury.bctr.cornell.edu/perch/resources/wounds-heal-pm-2.pdf

- Schuster, S. (2016, December 13). 28 Tattoos That Cover Self-Harm Scars. Retrieved from https://themighty.com/2016/12/tattoos-that-cover-self-harm-scars/

- Schuster, S. (2018, March 16). 28 Tattoos That Give Us Hope for Self-Harm Recovery. Retrieved from https://themighty.com/2018/03/self-harm-recovery-tattoos/

- Sweet, M., & Whitlock, J. (2010). Therapy: What to expect. Retrieved from http://www.selfinjury.bctr.cornell.edu/perch/resources/therapy-what-to-expect-pm-2.pdf

- Whitlock, J. (2018). Self-injury [Telephone interview]