How It Feels to Wear My Disability Blue Badge on the Train

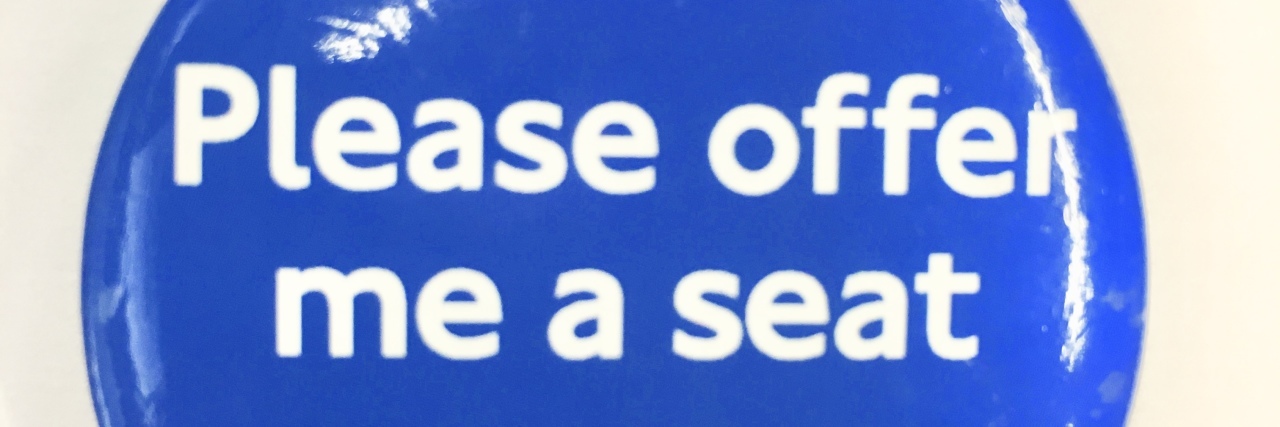

Should I pin the shiny blue “Please offer me a seat” badge to my coat or not?

I ask myself this question almost every time I travel on public transport in London. It’s part of my morning routine alongside wondering if an umbrella would be a good idea given the U.K.’s unpredictable weather, and checking several times to make sure I have my medication and supplements.

A few years ago an initiative was set up by Transport for London so people with a disability can apply for a badge and/or card that states “Please offer me a seat.” Alongside this initiative, certain seats on trains and station platforms became designated “priority seats” with a notice stating that a person should give up one of these seats if someone with a disability requires it. Hearteningly, the notice includes the statement that “some disabilities may not be immediately obvious” — a clear victory for those of us with so-called “invisible illnesses.”

I applied for the “Please offer me a seat” badge a year or so ago. I found it to be a surprisingly emotional experience. It brought up a lot of questions. Was I disabled enough to warrant a badge? Would people stare at me if I wore it? Would I get the often-voiced accusation “but you don’t look sick” if I asked for a seat? After receiving my badge it sat in its envelope in a cupboard drawer for a few months. Then I put it in my bag, and then my wallet. It was as though I was slowly letting it make its way to the lapel of my coat and so into my life.

So why didn’t I just use the badge right away?

My main reason for my hesitation has to do with the simple but emotionally complex act of making myself visible as a person with chronic invisible illness. I requested the badge as I have issues with standing for any prolonged period of time due to postural tachycardia and painful joints due to hypermobility syndrome and fibromyalgia. These conditions are invisible. I look no different to the other slightly harassed commuters on the train next to me, although if you look closely enough the fatigue will be obvious as no amount of make-up can conceal the dark circles under my eyes. I will definitely be furtively looking around for a free seat any time we stop at a station.

But I don’t look sick. I am invisible. I blend in with the crowd. And in all honesty, I like that. I want people to think I am just like them, even though I am aware that I should be brave enough to “own” my health, body and life just the way it is. Perhaps I am doing a disservice to others with disabilities by wanting to keep it to myself and not be proud of all that I am. Maybe that bravery and pride will come with time, but for now, I want to be perceived as just another commuter on my way to work to stare at a computer screen for the best part of the day.

Wearing a badge disrupts that illusion. It makes me visible. The shiny blue circle on my coat means I stand out from the crowd and no longer blend into the background. There’s clearly something different about me, and that visible difference means something deeply personal, my health, is no longer just mine but can be seen by others. What was private now becomes public. All of sudden the strangers around me whom I know nothing about know something about me. My disability, or questions as to what my disability could be, is on display for them to acknowledge and perhaps mull over.

There is a long history of people with disabilities having their health issues scrutinized and called into question. While one in five persons in the U.K. is disabled, and 19 percent of the working-age population is disabled, a House of Commons report describes how disabled persons regularly report being called “benefits cheats” and “scroungers,” and those who post online experience a “culture of fear” due to a “real risk of being falsely accused of faking their disability to gain social security benefits.”

Against the backdrop of such abuse, the question of wearing a disability badge and making my invisible illness visible to all is disconcerting, to say the least. I sit there wondering what others think. Do they believe I am disabled, or think I am faking? To say it makes me anxious is an understatement, and it is yet another reminder that I don’t fit into the (wrongful) social norms that surround assumptions of a “normal” person. I keep my head down when I wear the badge, pretending to be engrossed in my phone so I don’t meet the eyes of anyone who might give me accusatory looks or stares. It is always a relief to get off the train and unclasp the badge as soon as I can.

This may come across as a criticism of the initiative to supply the badges. Believe me, it isn’t. In fact, it is quite the opposite. It’s a criticism of the societal culture that makes invisible illness (and visible disability or illness) taboo, and often makes people feel self-conscious about their need to ask for accommodations for their disabilities. We shouldn’t need to “prove” our health status, and yet this is necessary in our society today. We shouldn’t feel embarrassed by our health, yet stigma and taboo often means we do. And we definitely shouldn’t fear abuse or accusations for something as simple as needing a seat on the train or bus.

Hopefully, initiatives such as the “Please offer me a seat” badge will be expanded and new initiatives to assist all people with disabilities will be put into place. It is only with such changes that social norms will begin to shift, and people with invisible illnesses won’t need to worry about making them visible in order to receive assistance.