“Who is that?”

“Why is your mom white?”

“Why don’t you act Black?”

These were questions that my elementary school classmates never hesitated to ask. As young as 5 years old, I remember feeling uncontrollable anger when asked to explain myself. I would immediately freeze, using a fake smile as a distraction. My mind raced to find an answer that would protect my happy-go-lucky persona for one more day.

After a brief pause, I would recite a script that my mother and I had created years earlier: “I am adopted. That’s why I look different from my mom.”

The most original follow-up question to this response was “Oh! Like Little Orphan Annie?!”

In second grade, I was partnered with a white girl in my class. About five minutes into this new seating arrangement, she turned to me casually and said, “My mom told me that black people are ugly.”

I immediately burst into tears and ran into the hallway, ignoring the yells from my teacher, whose only goal was to keep me in the classroom. I was scared, I was angry, I was hurt. I thought this girl was going to be my new friend. I didn’t think she was ugly. Why did her mom think I was? And why was this girl telling me this? Am I ugly? She’s right, I am ugly.

Afterwards, my white teacher (who I grew up across the street from) must have said something to try and comfort me, but her attempt was not memorable. The damage was done, and now I had even more proof I was different, and different was bad… being different made you unlovable.

School taught me to follow the rules, seek praise and to compete with my peers. In class, I came to expect scolding from teachers, even when I performed at the same level as my peers. I had anxiously committed to becoming the “smartest” person in my class. Teachers began to show off my work, but the compliments I received were always in the form of comparison. I began to push myself, with a goal: I never wanted to be embarrassed in class again. I tried to become perfect/better than, but I knew I was not. I knew that being “perfect” was a lie, and that I was a lie.

In middle school, I stopped hanging out with my old friends and let a “popular” white girl claim me as her own. I remember coming home after swim team practice, with 20 new voicemails flashing on the answering machine. My mother immediately played them out loud and we listened. Each voicemail was from my new friend, my new best friend, asking where I was, why I was not answering, and finally, demanding me to call her back. While my mother was worried, I felt proud and excited. Someone wanted me! Someone needed to spend time with me, and needed it now!

Flash forward to eighth grade. My mom tells me I will not be going to public high school. She explained to me that “the school all my friends would be going to was dangerous and could not provide me with the level of education I need to succeed.”

”Because I was Black,” she said, “I would need to use education as a tool to be better than the other public school kids (or at least to keep up with the rich white kids).” According to my mother, my future heavily depended on the college I would attend, what job I got and how much money I would make. Private high school would give me an advantage over public school kids (which I realized, I would no longer be considered).

After my mother had finished her monologue, I burst into tears, already picturing how horrible my next four years would be. I envisioned wearing a gross plaid skirt, an itchy sweater and not being able to make friends. Private school kids were white, rich and weird… definitely not “cool,” not “cool” in the way I had spent my middle school years trying to be.

My mother told me I should apply to simply see if I got in. So I applied to two boarding schools and one private academy. My mom combated my worries by repeating to me “Let’s just see if you get in. Let’s see if you even get a scholarship.” When my mom told me the price of boarding school, my anxieties lessened. We couldn’t afford that. I would just apply to make her happy. Eventually I would just end up staying with my classmates in public school.

But of course I got into one of the boarding schools that I was most afraid of, with a 90 percent scholarship. However, the scholarship had conditions. I would only receive the proposed scholarship if I lived on-campus. The school said I was “committing to being part of their community,” but I knew I had really just signed my life away. The boarding school was a small, seaside campus, with dorms named after Catholic saints and a looming brown church. The campus was only 15 minutes away from my childhood home, but I knew it was a different world, my fancy new prison.

At boarding school, I was bullied and became addicted to losing weight. I refused to be the ugly black girl. There weren’t many black people who attended my school, but there were tons of Nigerians, Koreans and other wealthy international students. All of a sudden I was in complete isolation, knowing I was one of the poorest students in my class, and coming to terms with the fact that everyone knew I was. I would deal with this pain by calling my mom everyday and crying to her on the phone. She was sympathetic, but was always focused on finding solutions. I knew the only real solution would be to return to home and public school, to the discomfort that I knew. But leaving boarding school was never an option, in my mom’s eyes. The struggle would be worth it, right?

Then in my junior year, my mom died suddenly, from lymphoma. It only took three months for her to die, but when I lost her, my little remaining hope died too.

From high school, to college, to countless jobs, I heard and experienced different varieties of the same hate, which first appeared to me at the age of 5. The difference now was that I had to deal with it alone and hoard any scraps of approval I could. There was no love left for me.

These are only a few snapshots from my life, and my experiences as a Black Transracial Adoptee. I constantly craved love and safety, but was never taught to listen to my inner needs. My connection to identity, race, biological family and sense of belonging was taken away from me the moment I was placed for adoption.

Only in the last month of my 26 years have I realized that these losses were not my fault. Realizing this truth looks like finding other transracial adoptees. It looks like listening to my body for instructions and following only those instructions. This recent energy shift came only after repetitive depressive episodes, moving away from conditional friends and committing to gentle changes in my thought patterns.

As I continue to heal, I realize I don’t have to edit my emotions or experiences for anyone. I don’t need to prove my happiness or prioritize other people’s comfort. As my friend told me, “Tone it down for no one.” I felt that, so I am now prioritizing myself, the person who was there all along. When you’re silent long enough, you forget you even have a voice. So going forward, I will not censor myself. Because I am love, more than fear. As the activist Maggie Kuhn says, “Speak your mind — even if you voice shakes.” Well Maggie, I’m working on it.

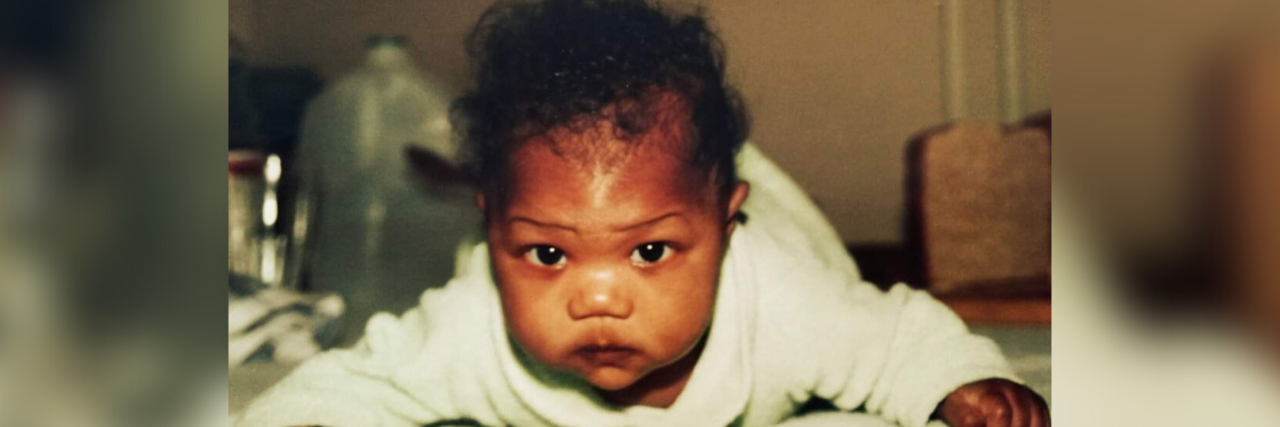

Image via contributor