The day before Thanksgiving this year will mark the 34 year anniversary of when I was diagnosed HIV+. Every year when this time arrives, I question why I am still here. Although a part of me can celebrate my life and be so thankful every year for having another year, another month, another day still being here, I am also sometimes consumed with guilt — survivor’s guilt. “Why me?” Why am I still here and so many others are not? I am part of a small minority who made it through the ’80s when AIDS was considered a death sentence and are still around to talk about it.

Today many people call me a “long-term survivor.” They tell me that it is a miracle that I am still alive, and they honor my life and fighting spirit. But in the mid to late ’80s, I didn’t think of any other title than that of being HIV+. In most people’s eyes or interpretations, I “had AIDS.” I had choices to make, but none of them projected to the foreseeable future or even held out hope. I just developed a close-knit support group of friends and family and then joined a very special group. We were a support group of HIV+ people who came together to listen, share, understand, support and love each other in a way no one outside the group could ever imagine, could ever believe, could even fathom. No one other than us could feel our pain and worry that was so thick you could feel it in the air in the rooms whenever we met.

We talked of our fears: of death, of pain, of hurt and how some of us were dealing with loved ones who did or did not know our plight, did or did not support us. We talked of our community that so many folks in the public could never understand. Those who misunderstood us, misunderstood HIV and AIDS and harbored fear themselves often ran from us, judged us, judged our current and past actions, judged who we lived with, who we loved with, and later who we were dying with. The public misunderstanding of our illness was so vast, so strong and so wrong that it made living and fighting off dying with HIV even harder.

To say that there was prejudice is an understatement, to say that there was hatred was a sad reality, to say that there was fear was dead on accurate — lots of fear, and most of it fear of the unknown. People partly told themselves what they wanted to hear because there were very few facts. People displayed their fear outwardly or let it fester internally, but we were the human beings living in the bubble, inside the fishbowl.

People assumed we were all gay or drug addicts. These were obviously misconceptions sometimes, but it was so much easier for some people to pigeonhole us so that they didn’t have to include themselves, including the possibility that they too may become HIV+. There were many who even felt that we “deserved” our (possible) death sentence and were callous and cruel beyond explanation, and their feelings often spread. It was easier to fear than to accept, to hate than to love, to judge than to try to understand.

At our meetings, we shared horror stories: of families, partners and friends who turned their backs on some of us and completely walked away in fear, anger, judgment or just to protect themselves in their minds. We talked of some doctors in the medical field from the military to the public who saw HIV+ patients wearing yellow hazmat suits and operated inside of plastic confines to take care of their patients out of obvious overblown fear. We talked of hospital rooms with bright neon signs at the doors of our rooms announcing our reality to all who entered — sometimes even family and/or friends who didn’t know of our diagnosis beforehand. We talked about side effects and weakness, and living while we were dying and dying to get over the pain of living. We often were outcasts and misfits if for no other reason than that it was easier to see us that way than to have to absorb the truth — and there was no one accurate truth. There still isn’t to this day.

I am blessed to still be here today. It is easy to question why, and it can be very hard to have to process these reflections.

So, the day before Thanksgiving is my anniversary. It is impossible for this holiday to come and go without my being reminded that I was diagnosed that day in 1987 — 34 years ago. I later figured out that I contracted the virus in 1985 — 36 years ago. I am strong and vibrant today and my “numbers” are very solid. My T-cells have risen back up from the very low numbers I had in 1997 and my viral load dropped from the highest number the tests could determine down to undetectable 22 years ago and have stayed the same.

Yes, I made some calculated changes to how I was living my life, and yes, I have a fighting spirit, but some of it also has to just come down to luck or divine intervention, depending on how you see things, which way you believe things. I think I am blessed and the God of my understanding has looked over me. Why? I am not sure. Maybe I will be able to accomplish some things, to give back, to take my experiences and by sharing them make a difference in people’s lives. Or maybe I am just still around because I have been hanging on.

Today, I am not sure. Today, I honestly don’t know if I have to be sure. Today, I am alive and in the simplest of terms, every breath is a bonus. Today, I continue keeping my commitment to telling my story, to painting a real picture that may change some viewpoints, to answer any and all questions no matter how personal they are in an attempt to be transparent, honest and true. And today, I appreciate the opportunity to do so!

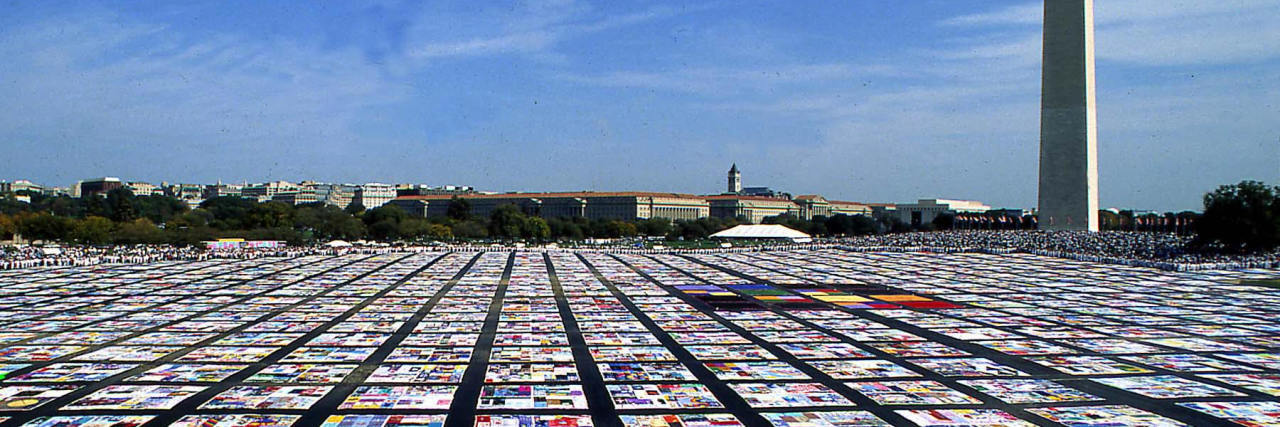

So, in retrospective sadness and current pride, I look forward to this anniversary every year and want to honor the spirits of those friends who I lost from those support groups, to honor those who I never met who shared our path, to honor all those hundreds of thousands of people who died along this path right here in the United States and millions around the world. So many of them became such good friends and I mourn their loss.

Image via Wikimedia Commons.